The latest league table from the NextGeneration Initiative reveals mixed results for housebuilders on their sustainability targets this year

At first glance you could be forgiven for thinking the housebuilding industry has been more interested in staying in business than building homes sustainably over the last five years. But with the 2016 zero-carbon target still in place, many housebuilders are taking steps to be as green as possible, even while the definition of zero-carbon homes and policy around areas including renewable energy and biodiversity remains uncertain.

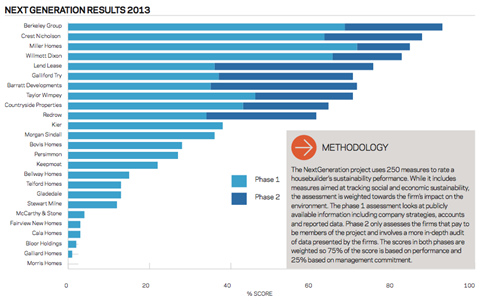

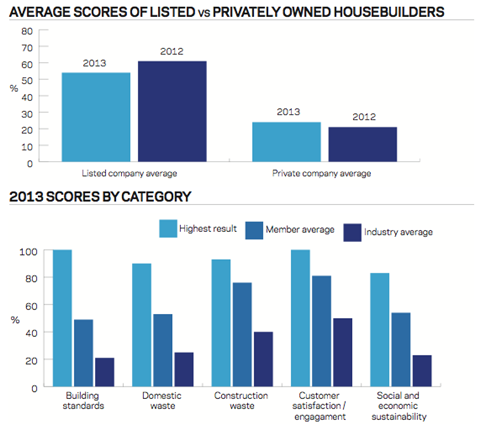

The NextGeneration Initiative, run by Jones Lang LaSalle and backed by the Homes and Communities Agency, has been monitoring and scoring housebuilders on the sustainability of their homes, construction and policies since 2006. The results for 2013 include the highest scores ever. For the first time the top four housebuilders have all scored over 80% and the average score of members of the project (see box) has risen to 75% from 71% in 2012, although the average score of all firms is up to 39% from 33%.

Julie Hirigoyen, head of sustainability at Jones Lang LaSalle, acknowledges that the benchmark may have reached a point where those at the top of the table now have little use for it, although there remains a huge gulf between the top and bottom performers. She says: “In terms of benchmarking there is not much left for them to learn.”

Indeed, taken as a whole there are areas in which the housebuilding industry has made impressive progress over the year. However, there remains a series of challenges for the lower performers to overcome if the industry is to perform as effectively as those firms that top the NextGeneration 2013 league table.

Miller Homes

Miller has made one of the biggest improvements in this year’s rankings. The firm increased its score by eight percentage points from 76% to 84%.

The firm, owned by the Miller family and private equity firm Blackstone, is part of the wider Miller group and has been building homes for 75 years. The housing arm reported revenue of £266m in 2012 and profit before interest of £14.5m.

Garry McDonald, procurement and sustainability director at Miller, likens the firm’s sustainability approach to the British cycling team’s ethos of “marginal gains”, where multiple small improvements are targeted to produce results.

“We’re just getting everyone doing the simple stuff. I think the key to it is to demystify sustainability,” he says. “Our scores have increased across all of the sectors. Our score for health and safety has increased and public reporting has increased.”

Giving an example of one smaller change made in the past year, he says the firm started monitoring the water it used in its homes between completion and sale, using the homes’ own water meters, which prompted it to change its approach to watering turf on the development to cut down its water use.

McDonald adds that a lot of progress has already been made in reducing the carbon impact of homes and their construction and that the social sustainability elements to planning and building developments are key to progress in future.

Miller also had the highest phase one score (based on publically available information) of any housebuilder. That, McDonald says, is because “you have to back yourself” and points to the firms record of publishing data since 2007 to show how ingrained transparency is.

Is he worried that putting a lot of information in the public domain might damage his competitive advantage?

“Other firms could come in and steal your ideas, but you can go and watch Manchester United, that doesn’t mean your team can become Manchester United overnight,” he says.

Unclear messages

The policy environment remains in a state of flux. Some policies, such as zero-carbon homes, will require housebuilders to decide how they go about meeting set performance targets, but it’s not yet clear what will be acceptable and what won’t. The government is also planning to remove local authorities’ ability to make demands for homes that perform above the standard required in the Building Regulations, and to scrap the Code for Sustainable Homes, arguably removing guidance for how to take steps to stand out from the crowd on sustainability.

However, it is clear that many of the NextGeneration housebuilders do not need guidance from the government in order to build more sustainably. Perhaps one of the more impressive pieces of progress that emerges from this year’s report is the increasing level of post-occupancy evaluation. Sinead Burke, senior consultant at JLL, says that the more complex nature of modern homes is necessitating this kind of evaluation to make sure they are working correctly. “If you bought a car you wouldn’t expect to drive it away and never see the dealer again; you’d go back for servicing and so on,” she says, adding that more firms are seeing this as an opportunity to capture information for themselves and provide a better service for customers by testing and improving the efficiency of their homes.

Hirigoyen adds that some developers are including facilities for people to manage domestic waste on their developments. “Developers have moved into the scheme management role, post completion and that’s quite new,” she says. “That suggests to me that there is a longer term embracing of their responsibility. It’s partly because those schemes take so long [to build out] and partly because there is a management value to being there once people have moved in.” However, it is clear that this isn’t consistent across sectors. Simon Wingate, technical director at Kier Homes, says that his clients, mainly local authorities, largely don’t request data on homes’ performance, so Kier doesn’t often collect it.

More materials

Another area of improvement highlighted by the report has been collaboration through the supply chain to get more sustainable products. Burke says more sustainable products are being prioritised in some housebuilder procurement processes. She adds that firms are realising that some materials that come from energy intensive industries, such as steel and cement, are subject to higher levels of price volatility. So, reducing their reliance on such materials either through greater recycling or different construction methods has a tangible business benefit, which is often an environmental benefit as well. “The standards are being put in place at an EU level that will allow you to look at those things more easily,” she adds.

However, John Tebbit, deputy chief executive of the Construction Products Association, says housebuilders still aren’t keen on new products that require a change in the construction process, even if they have benefits attached. “Individual products are quite hard to sell unless they just fit in and do something better than the previous product,” he says.

Berkeley

Berkeley topped the rankings this year, as it did last year, and became the first firm to score over 90% in the process.

Berkeley is one of the biggest housebuilders in the UK with revenue of £1.38bn in 2012-13. The listed firm reported pre-tax profit of £271m for the same year. It is focused on London and the South-east and traditionally serves the owner-occupier market. Although it also does a number of large-scale regeneration projects that have a broad spectrum of property types.

Karl Whiteman, division director and sustainability lead at Berkeley, says the firm’s focus, when it comes to sustainability, has shifted towards social elements and climate change adaptation. “We’re now building very thermally efficient homes, we have to be mindful those homes don’t suffer from overheating,” he says. He adds that balconies that provide shading and soft landscaping, which does a better job of dissipating heat than hard surfaces, are being used in its developments more and more.

But isn’t adding in such features a cost that’s difficult to recoup? “I think a lot of the things we can do will create value rather than add costs,” he says. “For example, where we have had to use sustainable urban drainage systems to cope with surface water, turning those into a water feature or swale, can actually create value.”

Whiteman says the next challenge the industry faces will be balancing sustainability and demand for housing as the economy returns to growth. But here he says BIM and offsite construction will be able to streamline the construction process to balance all necessary goals. He adds that the industry has a pressing need to adopt these technologies like never before.

He says the firm’s focus in future years will be proving its developments are not just environmentally and socially sustainable but economically sustainable, with jobs and places for business as well. “I think creating wonderful places is socially and economically sustainable in the long term. As an industry we need to make sure we are creating socially and economically good homes,” he says.

Working together

Despite greater collaboration between housebuilders and their suppliers, the sector continues to have a low level of research and development (R&D) spend compared to other industries. Burke says it’s around 1% of revenue, while pharmaceuticals invest closer to 5%, which she argues is a weakness if housebuilding is to become increasingly sustainable. However, she says that she expects the increasing sustainability demands of regulation to drive increased R&D.

Individual products are quite hard to sell unless they just fit in and do something better than the previous product

Chris Tinker, executive director at Crest Nicholson, says government plans to rein in the proliferation of local housing standards across the country will enable housbuilders to collaborate more with their suppliers to improve performance because of economies of scale. He adds that Crest already does this by building all its homes to level four of the Code for Sustainable Homes.

However, despite the fact that the most sustainable housebuilders are not asking for government directives, the cloud hanging over progress on sustainability is still policy uncertainty. Wingate argues it is making it difficult to plan developments ahead. He says: “The problem is that sooner or later we will be told, ok, we’ve got a site and you need to hit that target, but the industry has to build up to it.”

A key government proposal is the abolition of the Code for Sustainable Homes, which has prompted some vocal criticism in the industry. But the NextGeneration report has found there are few homes being certified under the code, figures from the Department for Communities and Local Government show 47% of new homes were given a certification under the code in 2012-13, which raises questions about its efficacy.

Nonetheless, Hirigoyen describes the government’s plans as “disappointing”, saying that the code has “traction in the industry” and allows cross market comparison. She argues improvements will be harder to drive or measure without it.

This is an area that the housebuilding industry cannot fix on its own but there are many things it is already doing. With an ethos that embraces the lifetime operation of a home and greater collaboration through the supply chain, the industry has the tools to meet its sustainability targets - even while the policy environment it operates in is in a state of flux.

No comments yet