Can consultants afford to keep their regional offices open?

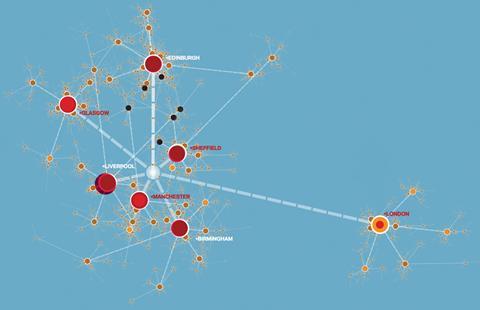

Gardiner & Theobald’s decision to close a number of UK regional offices, as revealed in Building two weeks ago, highlights a growing geographical divide in the industry. More than ever, construction is split into a two-speed economy: while London is seeing skyscrapers - not least the Shard - take shape and streets dug up to make way for Crossrail, the life has all but drained from the wider UK market. And for consultants, who sit at the front end of projects, often with little visibility of their forward pipelines of work, the issue is even more acute.

And Gardiner & Theobald (G&T), of course, is not the only one to notice. Steve McGuckin UK managing director of Turner & Townsend (T&T), which has nine English offices as well as three in Scotland and one in Belfast, says: “I travel around the UK a lot and you can see what’s happening. In Manchester and Liverpool, you will still see people driving around the centre in Porsches, but off the beaten track it is certainly not like that.”

According to Experian Economics’ most recent report on construction in July, new work output in the first quarter of 2012 fell across nine of 11 regions in England, Scotland, and Wales. The exceptions were Greater London, which grew by some 9%, and the South-east (+0.9%). Experian recorded particularly severe, double-digit declines in new work output in Wales (-17%), the West Midlands (-14%), Scotland (-13%) and the North-west (-11%).

So the question is, should consultants decide that enough is enough and close underperforming regional branches, or is it worth finding imaginative ways to keep the fires the burning outside the capital for when the market finally does return?

Shutting up shop

Consultants are responding to the skewed state of the UK market in a variety of ways. Some will decide to close offices. Hence G&T’s decision to “amalgamate” its Cardiff office with its Bristol branch, and its Birmingham with its Oxford office. This restructure of the regional business, which was responsible for a quarter of G&T’s £110m turnover in 2011, is intended to concentrate resources on infrastructure and overseas markets (see “Following the work”, below). Tony Burton, a senior partner at G&T, says: “We have always adjusted the business model to the opportunities in the markets in which we operate. Sometimes that means closing an office, right-sizing and amalgamating offices or sometimes it means exploring new sectors or services.”

Gleeds, meanwhile, is in the process of closing its Gloucester office. Richard Steer, chairman of Gleeds, which got 75% of its £74.4m 2011 turnover from the UK, says: “You have to respond to the depths of the recession and if that means closing an office, so be it. But we are transferring [most] of our 12 Gloucester staff to Bristol, from where we’ll maintain a presence in Gloucester.”

At T&T, which drew 46% of its £275m 2011/12 turnover from the UK according to its last annual report and where turnover is roughly split between London and the rest of the country, “consolidation” of regional offices is not planned, McGuckin says. However, he says he understands why closing a branch may be necessary at times for some firms.

“If an office has not made any money for two years but you think it’s going to turn around in another year you are kidding yourself. One the hardest things in life is to recognise reality, accept it and act on it. But as a businessman you’ve got to.”

Indeed, McGuckin says T&T’s regional offices are under constant scrutiny. “When a lease on an office is up we take a view on whether we need somewhere smaller, bigger or to close. Our lease breaks all fall at different times so we are reviewing offices on a close to quarterly basis.”

Yet he is sympathetic to anyone reluctant to shut an office. “It breaks your heart to lose capacity you have built up over 10 years.” Exiting a region will also leave consultants at a disadvantage if work picks up. “If you’re not there during the recovery, clearly you will miss out,” he says.

Operating from the regions allows us to be more competitive in the London market

David Stevenson, Edmond Shipway

It is also possible that an office closure could lead a consultant to miss out on work happening now - scant as it may be. At Mott MacDonald, for whom London made up 50% of its £337m 2011/12 UK turnover, Guy Leonard, regional managing director, Europe, UK and Africa, says: “Is it important to keep offices in the regions? Absolutely. Some clients don’t mind where you do the work but many do - you’ll struggle to win work in Scotland, for example, without a local office.”

Clients may want local knowledge and the ability to meet in person and many, especially in the public, transport and utilities sectors, are committed to employing local people. Mott MacDonald has an office in Cumbria, says Leonard, to help its nuclear power client Sellafield meet such commitments.

Shutting an office is also “cripplingly expensive”, points out Neil Clemson, managing director of London and the South-east at Faithful + Gould (F+G), which draws 70% of its UK income of £102m from outside the capital. “You suffer reputational damage and financial costs, there are personal costs to people losing their jobs and you reduce your capacity for increasing workload,” he says.

Toughing it out

So how can you hang on to a regional office in a tough local economy? F+G has benefited from having a powerful parent, Atkins. Clemson says: “We might have withdrawn from some of the fringe places [otherwise]. If you are faced with a long and expensive lease for a small team in a depressed market you might have to close.” However, F+G has been gradually amalgamating its offices into Atkins’ branches since 2002, as leases expire.

Capita Symonds, which gets a third of its £338m UK revenue (2011/12) from London, is tackling the problem by trying to pro-actively foster its own work opportunities. Jonathan Goring, managing director, says: “We’re responding to scant inward investment in the regions by finding ways for the private and public sectors to create income and that, in turn, creates jobs in construction.” One idea is to install commercial retail in hospital receptions. So far Capita has been involved in delivering five such projects, which have seen branches of Boots and Starbucks installed inside general hospitals.

Another tactic is to assemble a workforce able to work in multiple sectors. Leonard says this is why Mott MacDonald’s regional offices are “sustainable, if not growing”. “We have staff who are multi-skilled and we tend to work in sectors that don’t tend to involve leading edge technology, such as water and highways, which means staff can move around easily.” To ensure this continues, younger employees are given experience of multiple sectors.

Our ability to respond quickly to the changing landscape is a benefit of being financially independent

Tony Burton, Gardiner & Theobald

A popular way to keep regional offices going is to channel work from London or overseas to them. Burton says: “It is good business practice to utilise the skill-set available to you, and that sometimes means involving teams from a different office or regional location who have unique skills required for a particular project. Our employees work flexibly on projects across regions.”

Regional offices can even be transformed into fully fledged hubs for specialist skills, as at Gleeds and Aecom. Gleeds has focused its Newcastle office on producing bills of quantities, while Warrington specialises in energy and is one of the firm’s best performing offices, according to Steer. He says: “If you have a weakish local market, this means you can keep the office open, as long as it is making a profit on its specialisms, so it is ready for when the work comes back.”

Steve Morriss, chief executive, Europe, at Aecom says: “Our Edinburgh office is a centre of industrial expertise, so we have done work for clients like Rolls Royce and Diageo there.” The Cambridge office specialises in the education sector and Oxford in health and science. Following this strategy, the firm made roughly 25% of its £355m 2011 UK revenue from London and 75% from the regions. Morris says the approach suits Aecom’s policy of providing expertise from its global network to clients. The model can be enhanced by strong ICT infrastructure, such as easy computer file sharing, instant messaging and video conferencing, as well as hot desking and flexible working. F+G has rolled this out and Mott MacDonald is about to. Leonard says: “The new ICT system will help people work together on the same project from different locations.”

The drawback of this can be, as Steer admits, that this “back office” model can damage morale. “There is a danger with morale when the exciting projects are not there - but then this is a problem for the whole industry.” However, Morriss insists it can work well, keeping regional offices vibrant, but that these specialist focuses aren’t - and should not be - imposed from above. “It’s based on local enthusiasts and expertise that has naturally developed in a particular location,” he says.

Flexibility, then, goes a long way to tackling the London versus the regions problem. Whether inventing your own projects, developing teams that can switch between sectors or working on projects in different geographical locations. In the skewed UK market the more adaptable the consultant, the better it will fare.

STICKING TO THE REGIONS

Consultant Edmond Shipway has 70 staff in eight offices in the UK, including three in London. For this £6m-turnover consultancy, a strong presence in the regions and a light footprint in London is a deliberate strategy.

David Stevenson, managing director, says: “We can see there’s work in London and so we’ve added a business development manager to that office.” The London office brings in revenue of about £200,000, but Stevenson plans to grow this to £1m.

However, he will not be beefing up the London office to do it. “Operating from the regions allows us to be more competitive in the London market,” he says. “Our property and staff costs are significantly lower and we’re able to take advantage of some really good leases in the regions.” For example, the Nottingham team is just about to move from an office where the rent was £17 per ft2 to one where it will pay just £8 per ft2. “This has a dramatic effect on profit and loss,” says Stevenson.

FOLLOWING THE WORK

Tony Burton, a senior partner at Gardiner & Theobald, recognises that as desirable as it may be to keep an office open, when it no longer makes financial sense it’s time to make the hard-headed decision to close the doors. He says of the company’s recent regional restructure: “If activity emerges in a new market we will consider opening a new office, as has been the case in Sweden and the US, where we have just opened new offices in San Francisco and Miami. Equally, if a market slows down we also respond. We believe that is good business practice and our ability to respond quickly to the changing landscape is a benefit of being financially independent. We can be fully flexible and light on our feet with our business model.”

Burton says that the decision to close come offices “allowed us to reduce our overheads”, while amalgamating the offices with other branches means that the firm retains a presence in the region.

Neither does he feel a vast network of UK offices is necessary: “We believe it is very important to serve clients wherever they choose to undertake projects. We do this from our network of offices, site-based teams and by seconding staff into our client’s organisations. It doesn’t necessarily follow, when going with a client into a new region or a country, that we will open an office there. We don’t have offices in every location that we have projects - that would be impractical.”

No comments yet