The launch last week of a new payment charter adds to the legitmate pressure on contractors to pay their subbies promptly. But this pressure could also starve contractors of the cash they need to invest, push up prices, and even push some firms over the edge

Last week’s launch by chief construction adviser Peter Hansford of a new payment charter designed to help subbies get quick access to money owed on jobs is just the latest initiative to put the pressure on clients and main contractors over payment times. This charter, which has been drawn up by the joint industry-government Construction Leadership Council, will commit signatories to paying within 30 days by 2018, reducing or eliminating retentions, and adopting a “transparent, honest, and collaborative approach” to payment disputes.

How successful this will be depends on it achieving widespread take-up and then being subsequently enforced, as promised, through measurable performance indicators. It comes after a raft of other initiatives. These include a push to speed up payment on government contracts with the Cabinet Office’s memorably titled Procurement Information Note 2/2010, a separate government initiative around supply chain finance, and - possibly most significantly - a drive to expand aggressively the use of project bank accounts (PBAs) on public sector work.

This broad drive, which has cross-party political support, is being met with little overt resistance from contractors, who can’t easily in public counter the logic that they should be paying subbies fairly and promptly. The devastating impact of the industry’s culture of late payment on specialists and other subcontractors has been well documented in Building and elsewhere. But fixing the problem inevitably comes at a cost to main contractors. For them this push comes at a time when the lifeblood of available cash is continuing to drain from their balance sheets. An analysis of just the top six listed major contractors shows they have lost £400m in working capital in the last year alone, taking that portion of the sector to a net debt position - the result of over five years of recession.

When contractors’ borrowings are greater than the cash in the bank, it greatly restricts their ability to trade and invest as they’d like. One analyst house, Liberum, is even predicting that contractors will have to resort to rights issues to raise money simply because of the payment charter. Now a few contractors are saying in public they may have to increase margins in response, despite continuing government austerity. So could this drive to make them better corporate citizens really hit them where it hurts?

Financial strain

Martin Chown, procurement and supply chain director at the UK’s biggest contractor, Balfour Beatty, and the man in charge of the firm’s recently introduced supply chain finance initiative, is sanguine about the effects of the increasing pressure over payment on the firm. He says Balfour, despite being publicly criticised last year by glazing subcontractor Dortech for its payment practices, pays the “vast majority” of its bills within 30 days, and therefore won’t be overly affected by the drive. “The effect of these changes will depend more or less on where you’ve been in the past,” he says, adding that the firm has not yet decided whether to sign the payment charter. If Balfour did, though, he says, it would not signify a “dramatic tectonic shift” for the company. “The industry has a responsibility to pay on time,” he insists.

The effect of these changes will depend more or less on where your company has been [on payment times] in the past

Martin Chown, Balfour Beatty

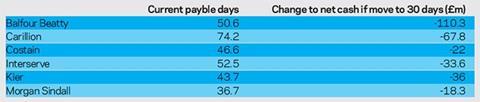

An analysis of the impact of the government’s payment charter by analyst Liberum, however, doesn’t share Chown’s optimism. Its estimates of contractors’ current payment times (see box overleaf) show Balfour Beatty coming out as one of the worse payers (though the figure includes its international business), averaging 51 days, with only Morgan Sindall anywhere close to the payment charter’s 30-day target. Carillion, however, is estimated to be by far the worst performer, averaging payment in 74 days, though the contractor maintains this is a “significant” over-estimate produced without accurately reflecting Carillion’s actual supply chain spend and payment practices in its other markets. In total, Liberum concludes that for the six to move to 30 days would squeeze nearly £300m of working capital from their balance sheets, leading to a requirement for more rights issues. Liberum’s Joe Brent says: “If nothing else happened, shorter payable days would result in increased net debt and potential financial strain, which would of course impact adversely upon the valuations [of contractors].”

Where Liberum does agree with Chown is over the variability of impact. Balfour Beatty alone, on this analysis, would see working capital reduced by more than £110m if it moved to 30 days, where Morgan Sindall would lose just £18m. Alastair Stewart, building analyst at Progressive Equity Research, says these pressures could not come at a worse time in the cycle, with construction volumes having hit their lowest point, something that also acts to suck cash from their balance sheets. “Coming out of recession is when the real cash flow issues start to hurt, as work won two years ago can become hard to deliver amid rising prices. But generally those who have been the faster payers in the industry will be less affected than those who are slower.”

Making contractors pay more quickly doesn’t necessarily reduce contractors’ ultimate profit margins, but by reducing their access to working capital, limiting cash reduces contractors’ ability to react to the threats and opportunities in the market. The fact is that the ability of contracting to generate large amounts of cash is one of the reasons businesses accept the comparatively small profit margins it produces, as this cash can then be used for other things. Generating cash is therefore particularly important for hybrid companies, such as Morgan Sindall or Galliford Try, which use the money to invest in development projects. For the likes of Carillion, likewise, which has a support services business, the cash is used to fund the set-up costs of big outsourcing contracts. For smaller players the stakes are even higher: lack of cash is what drives businesses to the wall, so in the severest cases, holding on to payments owed is a tactic designed simply to keep their head above water.

In response a profusion of contractors have launched schemes allowing a form of supply chain finance technically known as reverse factoring (see box, below). This a way to allow the contractor to hang on to cash and for the subcontractor to be paid early at the same time, financed for a charge by a bank. However, anecdotal reports suggest take-up among suppliers, which typically pay the charge for early payment, has been low with many preferring to simply be paid on time. At Balfour Beatty, for example, just £20m of payments went through its system in the second half of last year, a fraction of the estimated £7bn Liberum says it pays to trade suppliers.

Project bank accounts

Without doubt, what concerns contractors most about this pressure on payment is the push to use project bank accounts on central government contracts. PBAs involve the setting up of a separate trust into which the ultimate client transfers payment for the project in advance. Both the main contractor and suppliers are then paid from this their respective shares of the fees at agreed points, meaning the total revenue for the job doesn’t pass through the contractors’ balance sheet. Crucially, therefore, contractors only receive their direct costs and profit margin - they don’t get the cash-flow benefit of winning the work.

There may well be unintended consequences to externally imposed measures aimed at reforming behaviour

James Wates, Wates Group

The Cabinet Office, which as guardian of the government’s construction strategy is overseeing the push on PBAs, is thought to be on course to hit a deadline of putting £4bn of work through the system by 2015, to the delight of subcontractors. Rudi Klein, chief executive of the Specialist Engineering Contractors’ Group, says government departments and agencies from the Highways Agency, Ministry of Justice, Crossrail and the Defence Infrastructure Organisation are all beginning to make use of PBAs standard: “With the payment charter there will have to be work to enforce and police it. That’s why I’ve been pushing for project bank accounts - they are the best way to address the payment problem, and it’s becoming a real success.”

Because this has a financial impact on main contractors, Progressive’s Stewart says they could simply respond to this by attempting to shave suppliers’ margins. “There is always a bit of a trade-off between the speed and the amount of payment - a subbie may be willing to accept a little less in order to be paid on time.” However, Balfour Beatty’s Chown rejects the notion it would ask for a cheaper price from subbies on projects using PBAs. Either way, the now strengthening market is making it more and more difficult for main contractors to argue down their suppliers.

Hence recent weeks have seen Paul Sheffield, outgoing chief executive of Kier, Mark Castle, deputy chief operating officer at Mace, and Graham Shennan, managing director at Morgan Sindall all fire warnings over the use of PBAs, saying that by changing the terms of trade they make contracts less attractive. Because of this, they say, prices on public sector work involving PBAs may have to increase. Shennan told Building that their impact has been “significant.” “Construction is not as cash-generative as it was, and ultimately the margins may have to go up to compensate,” he said.

One listed contractor chief executive, who declined to be named, said: “Clearly one of the main reasons contractors work is to generate cash to invest elsewhere. If contracting doesn’t do that, then prices are likely to go up. Our prices certainly won’t be as cheap on projects with PBAs.” He added that many suppliers were not even asking for them, because they were an “administrative nightmare” to use as a trust has to be set up and administered by the end client.

James Wates, chairman of contractor Wates Group, says the industry itself needs to take responsibility to reform its practices around payment, but agrees with concerns around PBAs. “There may well be unintended consequences to externally imposed measures aimed at reforming behaviour. For example, it’s not difficult to see that project bank accounts could introduce inflationary pressures into the industry at a time when the sector and the UK economy least wants that.”

In this environment, it is not hard to see why a number of contractors are rushing out supply chain finance schemes. For the main contractor this is clearly preferable to a world where PBAs dominate.

There is always a bit of a trade-off between the speed and the amount of payment - a subbie may be willing to accept a little less in order to be paid on time

Alastair Stewart, Progressive Equity Research

Any suggestion that this drive to improve payment will increase prices will be an anathema to a government committed to cutting the cost of publicly procured construction projects by 20% over the course of the parliament. But there is some - limited - anecdotal evidence the economic recovery is helping to solve the payment issues that subcontractors have faced as the market power shifts back in their direction. Wates and Chown both say that increasingly they see paying well as vital to securing good quality subcontractors at the right prices. “We should behave as we’d like to be treated ourselves,” says Wates. “That’s not motherhood and apple pie - it’s a competitive advantage through doing the right thing.”

Contractors now hope that an improvement in practices, combined with the economic reality of rising prices and margins, will conspire to force the government to re-think. As the listed contractor chief executive says: “I suspect PBAs will not be around forever, and the government is already beginning to understand it has made a mistake in pushing them. I think in five years’ time we may all be looking back and saying do you remember when we all had to use project bank accounts.” Certainly, that is what main contractors want. But, given public sector cynicism over their failure to reform payment practices over the last two decades, whether they get it is another thing.

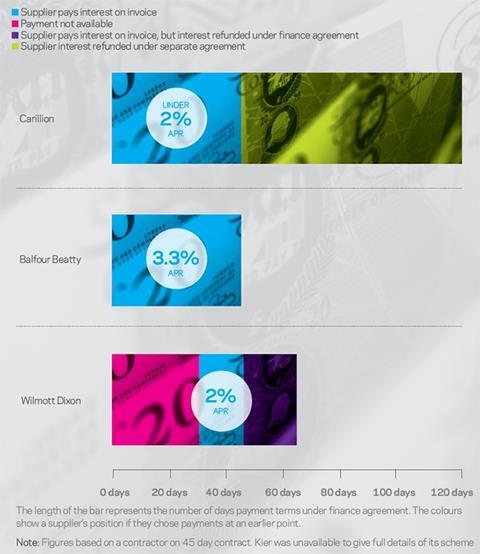

Supply chain finance schemes: How do they compare?

Supply chain finance schemes have been one controversial solution to the industry’s late payment issues over the last year. However, it is clear they are not all identical and many within the industry accept that there is a place for them in bringing flexibility to the payment system.

Indeed, Carillion’s scheme, which has proved the most controversial, mainly for the 120 day payment terms it requires subbies to sign up to in principle, has its supporters. Last year, Carillion produced figures that show 89% of firms using the system felt it had a positive effect on their ability to get paid promptly and flexibly, while 87% said they would recommend it to other firms.

Take away any additional costs and remove the lengthy underlying payment terms and such schemes are quite well received. Even Rudi Klein chief executive of the Specialist Engineering Contractors Group, and someone who has been fiercely critical of such schemes, acknowledged when speaking about Willmott Dixon’s scheme that some members of the supply chain would find a zero-cost finance system beneficial.

Objections to such schemes are often a matter of principle, such as the National Specialist Contractors’ Council’s objection to Carillion’s scheme on the basis it was “ethically unacceptable”. There are many that believe suppliers should simply be paid within 30 days or less and anything more is not acceptable.

But the commercial reality is less straightforward. For subcontractors that are paying high interest rates to finance their own businesses when payments are late, cheap credit financed by strong contractors can be very appealing, even if it means a contractual extension of their payment terms.

Liberum payment analysis

Liberum has estimated the average payment time of major contractors by working out the average amount each is likely to spend with trade creditors (assumed as 80% of turnover) each day. Liberum then compared this with the amount reported as owed to trade creditors in the firms’ end of year accounts, to how many days’ worth of payments were sitting in their books.

Net cash at major contractors

To read the full news analysis click here.

No comments yet