UK prisons are dilapidated, inefficient – and full. So when plans were announced late last year to close the worst of them and build nine new prisons focusing on rehabilitation, there was near universal approval. Since then, however, doubts have begun to surface over financing, timing and location

For years, prisons across England and Wales have been, to all intents and purposes, full. In December, there were 85,847 inmates, leaving a spare capacity of fewer than 2,000 places. The situation has recovered slightly from a nadir in 2014, when prisons faced their gravest overcrowding crisis. There were only 265 free spaces at one point, with 14 privately run prisons overseen by the likes of G4S and Serco paid to squeeze more offenders into their cells.

Chris Grayling, the then Lord Chancellor, refused to instigate what is known as Project Safeguard, a scheme in which police and court cells are used to accommodate inmates when prisons reach 99% capacity. The previous Labour government had been forced to introduce Safeguard, but it proved politically embarrassing and it was widely suspected by prison reform campaigners that Grayling did not want to face similar accusations of failure.

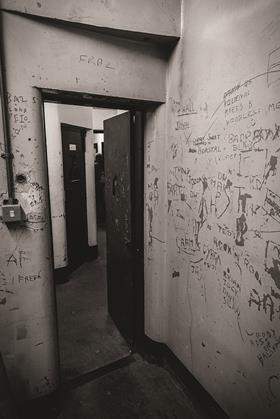

Grayling was replaced by former education secretary and chief whip Michael Gove last year, following the Conservatives’ surprising general election victory. Gove has been shocked by what he has discovered, particularly the poor state of Victorian jails that have been frequently criticised by Nick Hardwick, the chief inspector of prisons. Not only is the criminal legal system struggling to find cell space for offenders, it is forcing them to live in prisons such as London’s 174-year-old Pentonville, which Hardwick found to have bloodstained walls, piles of rubbish and high levels of violence.

They’re going to sell off places like Holloway to get money so they can build prisons in the middle of nowhere

Frances Crook, chief executive, Howard League for Penal Reform

In July, Gove surprised and pleased prison reform campaigners who had been sceptical of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) under Grayling, believing this was a department that was focused solely on cutting costs. Gove told the Prisoner Learning Alliance: “We have to consider closing down the ageing and ineffective Victorian prisons in our major cities, reducing the crowding and ending the inefficiencies which blight the lives of everyone in them and building new prisons which embody higher standards in every way they operate.”

Better prison conditions, should, it was calculated, help rehabilitation, lower reoffending rates, and therefore reduce the overcrowded inmate population. Lest anyone doubt his plans for a major “new for old” prison programme, Gove set out more details in November once he had secured his Comprehensive Spending Review settlement with chancellor George Osborne.

The pair took a joint visit to south London’s Brixton prison, built in 1820, and announced that “ageing and ineffective” Victorian jails would be closed, then sold to build 3,000 new homes.

The £1bn programme would see money raised from the sale of valuable inner-city locations used to fund the construction of nine new jails - five before the next election in 2020 - that could accommodate 10,000 inmates. This would be in addition to the UK’s first Titan megaprison in north Wales, a £212m facility being built by Lendlease that will hold 2,100 offenders.

Running costs would be reduced by about £80m a year, with Reading prison, where Oscar Wilde was jailed for two years in 1895, named by the Treasury as one of the first to be sold. Holloway, Europe’s largest women’s prison and where, in 1955, Ruth Ellis became the last woman to be executed in England, would close and be sold for perhaps as much as £200m, in less than a year.

Prison purdah

But politicians, reform campaigners and contractors eyeing up lucrative deals have been deafened by silence ever since. Reading, having already closed in 2013, was always likely to be sold, and Gove has signaled that Pentonville should be shut after describing it as “the most dramatic example of prison failure within the prison estate”.

Yet, three months on and the MoJ has offered no further detail on which jails will be redeveloped for housing and where these new prisons will be located.

This has led to fears that the MoJ could end up slipping behind on what already appears to be a tight construction schedule. “We’re now in 2016 and planning prisons takes a significant amount of time,” says Prison Officers Association general secretary Steve Gillan. “It will take some push to build five new prisons by 2020.”

A minister told Building that the MoJ is keen to announce closures “as late as possible”, so that sales are virtually completed and new sites have been bought and prepared. “The nature of prisons mean you need to maintain staff morale,” says the government source. “You make the announcement when you have the specifics to explain to officers, staff and inmates as far as possible what is going on.”

A leading MoJ official adds that the plans are “in progress”, while a spokesman insists there will be further announcements “in due course”.

But shadow justice secretary Lord Falconer counters: “Gove has talked a good game, [but] apart from Holloway being sold, there has not been any evidence where the money is coming from for rehabilitation. I assume the silence is because Osborne has not put the money where Gove’s mouth is.”

Some reformers fear the government has in fact only just realised the scale of its task. “There’s been very scant information,” says one leading penal reformer. “Ministers are still trying to make up their minds about where to close and where to build new prisons.

“I would take the focus on Victorian prisons with a pinch of salt. It’s not just the Victorian prisons that are not fit for purpose - the prison estate is a mess that contains a lot of inadequate buildings that cost an awful lot to maintain. Northumberland [built in the 1970s] is a remote jail built on an RAF airfield on the North-east coast and they’ve got a workshop with sewing machines in an old aircraft hangar. It’s 40 to 50ft high, so the heating bill alone is huge.”

Bob Neill, a former Conservative minister who now chairs the House of Commons’ Justice Select Committee, believes the MoJ will have to hand over a lot of the preparatory work to a property agent, a firm like Savills or Cushman & Wakefield. He is concerned the MoJ does not have sufficient in-house skills to negotiate the best prices for its jails or to buy land at reasonable prices, particularly given the department faces job cuts at its administrative centre.

“There is a question over whether the department has the capacity to deal with negotiating what are going to be high-end commercial property deals,” says Neill.

In particular, he is worried by rumours that many prisons have covenants that will stop them being converted for other uses, such as housing. Justice minister Andrew Selous has, though, written to Neill confirming that “there is no restriction contained in the title document” for Holloway, despite speculation to the contrary.

Neill told Building his committee will “probably want to” launch a broad prisons inquiry, which would include the estates programme and overcrowding, once Gove outlines which prisons will be sold. He adds: “There’s huge merit if this can be achieved. I remember going into some of those prisons when I was a barrister nearly 40 years ago, and they were grotty then.”

Where the new prisons will be built

Many campaigners believe the new prisons will be built away from communities so as to get them through planning quickly. This, though, cuts off prisoners from local services, such as education, as well as their families, which are all considered vital for rehabilitation and to prevent reoffending.

Frances Crook, chief executive at the Howard League for Penal Reform, sighs: “They’re going to sell off places like Holloway to get money so they can build prisons in the middle of nowhere.”

For now, the female inmates of Holloway will be relocated to Downview, a refurbished facility on the outskirts of Banstead in Surrey. It is thought the MoJ is already talking to developers and possibly investors from Asia about the sale of Holloway.

Some MPs concede that building prisons on greenfield sites in fairly remote locations might be the only expedient solution and “probably do make sense in terms of cost”. However, a senior Conservative backbencher says the property sales could rake in sufficient money so that the government could be “generous” in helping visitors meet expensive travel fares.

But the change of Lord Chancellor from Grayling to Gove has given Peter Dawson, deputy director at the Prison Reform Trust, hope that the MoJ will take “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to lay the foundations of a rational prison estate”.

Dawson argues: “He must start from the right principles: that there should be far fewer people in prison, they should not live in overcrowded conditions, and they should be held close to the communities into which they are to be released. That means closing many more prisons than are opened; and analysing where prisons are needed, not where they are profitable to demolish or cheap to build.

“A rational prison estate will be planned in the same way as schools or hospitals - providing space near where it is needed. Prisons can be an asset to a community, not just economically but with shared facilities for sport and education, for example, or cafes staffed by prisoners in training. Close to home means more efficient and more effective prisons, enabling collaborative working with local services like education, health and social care, and preserving the family links which will help prisoners go straight after release.”

Dawson also wants these prisons to be fitted with modern designs and practices, even letting prisoners have their own key so they can go in and out of their cells to attend appointments and workshops. A secondary lock would then be used by officers or enhanced IT, which would also be used to help educate and rehabilitate the prisoners.

“More of the same will not do - a radical approach to both location and design is overdue,” says Dawson.

Hopefully the silence means that Gove and his officials are being just that, sufficiently “radical” so as to build prisons that will help rather than hinder rehabilitation.

No comments yet