Phil Wilbraham, the man who oversaw two Heathrow terminals, now has to implement the airport’s new framework strategy, which means driving down construction costs

Standing in Terminal 2 of Heathrow it is fair to say that Phil Wilbraham, who oversaw the construction of the building, has some similarities with the gleaming new facility. In fact, he is bright, open and even reflective on occasions.

Wilbraham was responsible for the construction of both Terminal 2 as programme director and the more ambitious Terminal 5 as construction director for Heathrow. Now he presides over the whole airport as its director of planning and programmes after his boss, John Holland-Kaye, previously development director, was promoted to the role of chief executive.

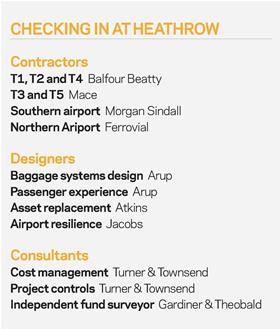

While speculation is mounting that the political pendulum might be swinging back in favour of a third runway at Heathrow, Wilbraham’s task is less glamorous: to improve the function of the whole airport estate over the next five years as it scales back its construction programme. Sir Howard Davies’ Airports Commission won’t reach its conclusion until next summer, but in the meantime Heathrow has appointed four contractors, each for a separate section of the airport, to deliver the five-year £1.5bn upgrade programme (see box, below).

The appointments, announced in March, mark a radical departure for Heathrow, which was previously a trailblazer for the introduction of frameworks to the construction market. Heathrow’s previous major project frameworks consisted of nine firms that had to then bid for jobs between £10m and £25m - larger jobs were open tenders to the whole marketplace.

Now with fewer firms in the mix, Wilbraham hopes there will be closer collaboration between client, consultants and contractors. The next five years will be an acid test of that philosophy, and Wilbraham is setting the construction industry some stretching targets to deliver against.

Rising to the challenges

“We are looking for a 15% increase of value,” he says. “So that’s looking to increase the revenue, increase the operating cost savings, or increase the passenger experience - for example, by reducing times for a plane to taxi on the taxiway.”

Over the next three years contractors will be judged, in part, on their ability to actually improve Heathrow’s operation - not just their performance on an individual project.

The challenges don’t stop there. He says he also wants to see a 15% real terms reduction in construction cost. Though he accepts prices will inflate over time - he hopes construction inflation will mirror the inflation of the retail price index - and he will be taking this into account.

He says: “We are expecting that because there is a pipeline of work that the contractors will improve over three years […] We are encouraging the contractors to come up-stream into the programmes to help the design team, our team, to get the most out of it.”

That early input is key because he says Heathrow as a client has a role to play in keeping costs down too. He says there is a commitment that once projects are signed off and investment has been given the green light, Heathrow will not make any further changes. “If we change things then the likelihood of costs coming down is reduced,” he says.

There are further targets. Wilbraham says he wants to see “as much built off site as possible” because of the “tight operational areas” at Heathrow. That focus may be seen as a grim irony for Laing O’Rourke, which has made a huge investment in off-site manufacturing plants in recent years, but did not win any of the Heathrow contracts. This happened despite Laing O’Rourke being shortlisted for three of the four jobs - more than any other firm bar Ferrovial, its partner in building Terminal 2.

“We are not doing anything of that scale [T2],” says Wilbraham. “I’m sure when you are doing something of that scale again that kind of facility [off-site plants] will be needed. We haven’t said goodbye to Laing O’Rourke - it’s just au revoir.”

Indeed, he says Balfour Beatty, which won the T1, T2 and T4 lot, was “leading the way” on modular building of M&E systems on Terminal 2B and the railway at Terminal 5.

Change to the model

Wilbraham says the change to a long-term partnership model of procurement has been bought about because Heathrow is “not going to be running with a mega project” over the next five years, meaning spending is less.

He believes that even with the scale of the previous investment programme, its previous frameworks, such as the complex build integrators framework, were, in retrospect, too large.

Wilbraham explains: “There were nine contractors on that framework. We definitely did not have enough work to feed nine contractors. So the right thing for us, and for them, is to get the right number. We feel four is the right number so they have a good workload here all the time.”

Wilbraham is keen to emphasise the new system is about building long-term relationships with contractors and consultants and that even a return to big new build projects - such as a possible third runway - would not mean a return to frameworks.

“We would look to build on what we have got now. We have very deliberately appointed the people we have because we wanted to have big companies involved who would be able to help us to then get going on a third runway. Others would need to come to the party, but if this is successful I see no reason why we would need to change the model. We would need more and bigger help,” he says.

But Wilbraham is focused on the next five years - not a runway that may never materialise. He is challenging the contracting sector, in particular, to deliver the efficiencies on cost and value that firms often claim they can if given a solid pipeline of work, but rarely have the chance to prove.

For the firms delivering that while battling rising staff and material costs will be a challenge. But it will be a great calling card if they pull it off.

Source

This interview was published in print with the head line: This is your captain speaking

No comments yet