The Co-op’s rigorous approach to sustainability on its HQ in Manchester sets it apart as a client - so are others less willing or just less able to make such a commitment?

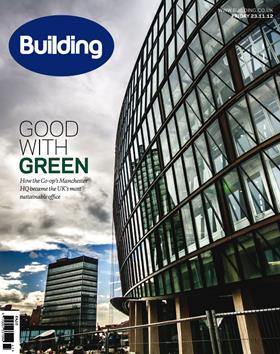

There is no shortage of reasons why the Co-op’s new Manchester headquarters - our cover project this week - is bound to attract attention. There’s its striking appearance, of course, and the painful fact that it is one of the few major commercial schemes outside of the capital to have made it to fruition of late. But perhaps more remarkable than either of these is the project’s approach to sustainability - not just because of its feat in becoming the UK’s highest-rated BREEAM office development, but for the lessons it can offer in maintaining a sustainable approach to building even in a recession.

The development, designed by 3DReid, was conceived back in the relatively heady days of 2008, when attaching eco-bling to projects was as commonplace as the lavish events being held to toast “sustainable” developments. Although the warning signs over future funding were there with the onset of the credit crunch, prolonged recession was still an unguessed prospect, and developers in the main were content to throw money at often ill-conceived add-on technologies (such as the stubbornly static wind turbines that originally adorned Will Alsop’s Palestra in London).

The sustainable nature of the building was always intended to be a differentiator for the client, rather than a ‘nice to have’ optional extra to be ditched as soon as the recession set in

The Co-op, by contrast, opted for less visible but more embedded and effective methods of achieving sustainability; directing its cash at innovative systems which enable the building to become more efficient as its temperature rises, and making the most of external design features to maximise gains from solar energy.

Its approach was far more about capturing what it regards as its own sustainable ethos in its new headquarters than it was about presenting a face to the outside world. And of course the scheme’s environmental credentials go far beyond straightforward legislative compliance. The sustainable nature of the building was always intended to be a differentiator for the client, rather than a tick box exercise or a “nice to have” optional extra to be ditched or compromised as soon as the economic reality of recession set in and the construction phase began.

Deep constraints on funding in both the public and private sectors have inevitably weakened the general rush towards spending on sustainability. The peer pressure to invest in sustainable construction has lessened as reduced budgets have hit more and more clients, and a lack of government focus on implementing intended policy drivers such as display energy certificates has slowed progress still further.

But the flip side of this is that a space is opening up for clients, and for construction firms, to use sustainable development as a way to set themselves apart from rivals far more readily than they could in the past. The fact that the Co-op’s building stands out so much is, without detracting in any way from its intent, aided by the constraints felt by other clients over the past four years. But the removal of much of the white noise from the green agenda creates some breathing space for companies to consider how far they genuinely want to commit to sustainability. And for clients like the Co-op, which want the buildings they use to align with their sustainable values, the case for doing so is clear.

Sarah Richardson, editor

No comments yet