Ofgem’s announcement last week that the six big energy firms face a competition inquiry has spooked the market and alarmed construction firms relying on new energy generation capacity. But are things really as bleak as they seem?

Last week’s announcement by energy regulator Ofgem that it was consulting on referring the conduct of the so-called “big six” firms to the competition authorities, had been long expected. The share prices of the firms barely flickered.

In fact, it is investors in construction firms who may well be feeling the biggest alarm, having had a few days to digest the contents of the announcement and its aftermath. Because for those involved in the construction of new energy generation capacity, the reaction of the big six to the announcement was striking. Two of them - Centrica, which owns British Gas, and SSE - said they would rein in their investment in new generation capacity. The chief executive of one, Sam Laidlaw at Centrica, said he was worried a future inquiry will lead to “no investment” in new plant - particularly gas-fired stations - for the two years the inquiry would likely take.

These firms argue that they cannot be expected to make significant new investments at a time when they have the threat of their forced break-up hanging over them - a threat increased by Labour’s pledge to freeze prices and likewise restructure the market if it gains power.

A reduction in investment would be a huge problem for the government, which has spent the last five years trying to get its electricity market reform programme off the ground in order to generate £110bn of investment in new power stations. Meanwhile Ofgem itself is warning that spare generation capacity has fallen so far that forced blackouts in wintertime will happen once every four years by 2015/16 if demand fails to fall. For the construction industry the concern must be that the promised workload from building new power stations and windfarms, already delayed, will now be further put off.

Some commentators have not hesitated in painting a very bleak picture indeed. When Ofgem itself was asked about the risk of discouraging vital investment, its chief executive Dermot Nolan simply said there was currently so little investment that a future investigation could hardly make things worse. An inquiry by the brand new Competition Markets Authority (CMA), which is liable to result from Ofgem’s announcement, would likely tackle the vertical integration of businesses that include energy generation, wholesale trading and retail businesses in single firms, and may force them to split or divest.

Gathering uncertainties

Peter Atherton, utilities analyst at Liberum, is scathing about the decision, which he says shows Ofgem surrendering its independence in the face of political pressure to get tough with energy firms. “We would expect an inquiry to freeze additional growth capex [capital expenditure] in the UK by those companies covered. The uncertainties created over future market structures would also likely dampen investment from those corporates not directly involved in the inquiry.

It is likely that the hiatus in power generation investment will continue and probably deepen… we would be surprised if any of the major UK generators were to move forward with power station investments while the inquiry is on-going

Peter Atherton, Liberum

“Therefore, it is likely that the hiatus in power generation investment we have seen in recent years will continue and probably deepen … We would be surprised if any of the major UK generators, who are directly or indirectly affected by the CMA inquiry, were to move forward with ‘big ticket’ power station investments while the CMA inquiry is on-going.” His view is backed by the actions of Centrica and SSE. In announcing it would defer plans to build two gas plants, Centrica’s Laidlaw said: “Clearly if we have this competition referral, our ability to invest is going to be handicapped, because you wouldn’t invest in new power generation if there was a possibility that you might have to divest as a result of a competition referral.”

Meanwhile SSE anticipated Ofgem’s move by announcing its own price freeze alongside deep cuts to its programme of investment in offshore wind. It said it would not progress with one 340MW offshore wind plant, and would not make any further expenditure beyond that already committed on three others, together worth a staggering 10GW of potential capacity.

Its explanation for its decision, following a strategic review of its wind business, shows how finely poised the investments in major energy infrastructure are, despite the government’s programme of Electricity Market Reform (EMR) supposed to support investment.

Jim Smith, SSE’s managing director of generation development, said: “There are two major hurdles that projects currently have to overcome. The Levy Control Framework, which has the reasonable objective of controlling costs to customers, means there is limited support for offshore wind. The second [hurdle] is cost - the future of offshore wind farm development depends on a sustainable and lower cost supply chain.”

Counting the gigawatts

In this context, Ofgem’s consultation on referral to the CMA, is just one more factor inhibiting investment. Which is bad news for the UK’s wider proposed offshore wind programme, a major plank of plans for new capacity. Of the Crown Estate’s pipeline of 29 projects in planning or under construction, half were originally being progressed with the involvement of “big six” firms. These projects accounted for over three-quarters of the proposed 40GW of generating capacity planned in UK waters.

Even before Ofgem’s announcement, the signs weren’t good. Centrica pulled out of the 580MW Race Bank scheme in December. Before last week, 3.2GW of potential generating capacity had already been wiped from the UK’s pipeline in under six months.

Unsurprisingly, the extent to which Ofgem’s move has worsened this situation is up for debate. Simon Rawlinson, partner at EC Harris, says Labour’s announcement of its own energy market review and price freeze had already significantly chilled investor sentiment.

“It introduced enough uncertainty to get energy firms worried about their investment. Many had already put off decisions until after the election.”

In addition energy companies are finding recent investments have not been reliable revenue generators. A spokesperson for RWE, the German owner of Npower, said it only had one CCGT gas power station in its pipeline, in part because its recent investments at Pembroke and Staythorpe were “not making as much as we thought they would”.

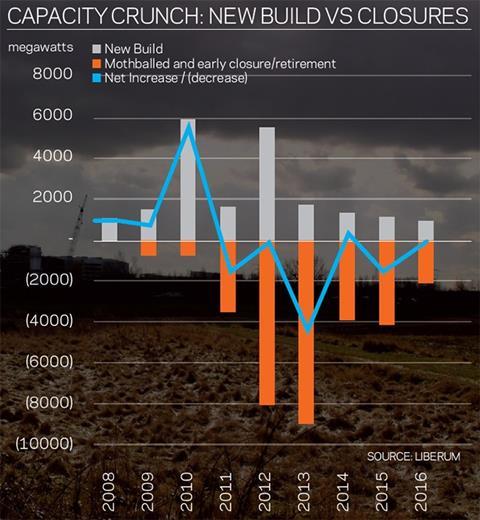

Beyond the headline moves, it is difficult to get a full picture given the lack of reliable data in the public domain. Ofgem’s most recent electricity capacity report, published last summer, paints a bleak picture, showing excess generating capacity falling to just 4% by 2016. It predicts installed capacity in the sector falling from over 82GW in 2012/13 to around 76GW in 2015/16, before starting to pick up slowly. “Since last year, the outlook for the supply side has deteriorated and industry has announced the withdrawal of more than 2GW of installed generation capacity in the near future. Further withdrawals are still likely,” Ofgem says. But these falls are as much to do with an accelerated programme of retiring old-fashioned power stations, driven by both regulatory requirements and the falling price of coal, as poor investment in capacity. Atherton’s own analysis of the UK market for Liberum (see graph, below) shows a huge loss of capacity of over 8GW in 2013 alone. So while the outlook for the UK’s ability to generate as much power as it needs is undeniably bleak, this doesn’t necessarily mean that no construction work is happening - despite Ofgem and Centrica’s rhetoric.

Investment pipeline

Firstly, not all of the big six have said they will rein in investment in light of Ofgem’s decision - indeed even SSE, which pulled back its wind farm programme, made clear it still plans £1.6bn of capital investment in the UK and Ireland in 2014/15. Iberdrola, owner of Scottish Power, recently promised continued major investment in the UK market, and said this week those plans were unchanged. Likewise RWE, which retains a £500m pipeline of windfarm projects, said the decision changed nothing. EDF and Eon both welcomed a competition inquiry as a chance to vindicate their performance, with EDF also pointing to its planned investment programme.

What figures there are on gross investment indicate that, far from a total hiatus, spend has been rising quickly, albeit from a low base, in the last few years. Figures from the Office of National Statistics show that the annual value of the construction of new electricity generation infrastructure trebled between 2009 and 2013 (the last full year for which figures are available), to £3.7bn. Likewise new orders in the same market increased four-fold over the same period. Consultancy KPMG estimates the overall output from energy construction projects (as opposed to just electricity) rose from £3.3bn in 2010 to £4.7bn in 2013. This investment would have to rise substantially more quickly to meet government targets - but the trajectory is in the right direction.

Since last year, the outlook for the supply side has deteriorated and industry has announced the withdrawal of more than 2GW of installed generation capacity in the near future. Further withdrawals are likely

OFGEM, electricity capacity assessment report, 2013

The government’s argument, in response to concerns over investment, is that new players outside of the big six will increasingly be drawn into the market - the latest example being the £461m investment by Japanese firm Marubeni and the Green Investment Bank in the Westermost Rough offshore wind farm. Matt Cuchra, power and utilities partner at KPMG, says there is some truth to this, because of the way the government has structured its Electricity Market Reform programme, which guarantee companies long-term returns on investment in generating capacity: “Energy companies have traditionally included both generation and retail businesses in order to guarantee a market for the electricity they generate. But the logic of EMR means that price is now guaranteed by contract, so the rationale for vertically integrated businesses isn’t so strong. The question is whether there is a new business model around investing in energy generation that doesn’t require a retail business.”

In addition, for construction firms the sheer volume of capacity coming offline will open up opportunities for demolition and decommissioning.

But these positives must be offset by the reality that new entrants are likely to be able to negotiate a higher energy price guarantee under EMR if the “big six” decide not to bring forward development proposals. Atherton says “At the very least, the absence of the large traditional utilities from the [capacity] auction suggests that the price the government will need to pay to attract new gas fired capacity will increase.” This means power will end up costing end users more.

There is undoubtedly a chance that a CMA review will create a new operating environment in the UK that works better to encourage future investment in the UK’s energy infrastructure.

But while the current position for the sector’s contractors is not as bleak as it is often painted, it seems clear the Ofgem announcement is in the short term likely to exacerbate the caution of investors already nervous about betting the farm on the UK market.

‘Clearing the air’

Energy regulator Ofgem proposed last week that the “big six” energy firms - Centrica (British Gas), EDF, Eon, RWE (Npower), Scottish Power (owned by Iberdrola) and SSE - be referred to the newly-formed Competition Markets Authority for investigation. It will consult until May 23 on this decision, with the CMA not thought likely to be in a position to start an investigation until the autumn.

Ofgem said it was proposing this because of falling consumer trust in energy suppliers amid rising profits, and in order to “clear the air” by providing a final decision on whether the market was working fairly.

The CMA has been formed from a merger between the Competition Commission and part of the Office of Fair Trading, and has beefed up powers to order the breaking up of companies, financial penalties and even criminal prosecutions. The CMA is allowed a maximum of 18 months to complete an investigation, though there is an option to extend this by six months under “special circumstances”, and it must implement any remedies within six months of the conclusion.

No comments yet