The government is trying to renew 3,500 schools in 15 years using teams of confused officials, increasingly resentful contractors and a system that combines surreal bureaucracy with huge wastes in time and money. Eleanor Goodman and Katie Puckett explain why Building Schools for the Future continues to underachieve

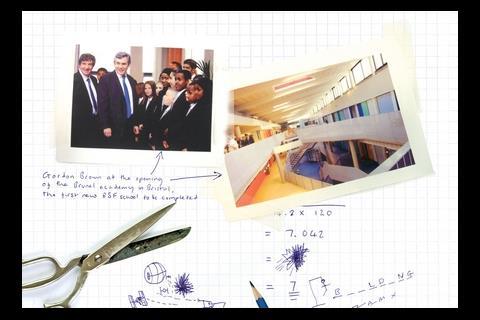

When the Brunel academy in Bristol opened earlier this month, the prime minister leaped at the chance to trumpet the government’s commitment to education while cutting the ribbon in front of the national media. For Gordon Brown, this was a no brainer. The £24m secondary school, designed by Wilkinson Eyre and built by Skanska, was the model of a modern academy: it’s architecture had been praised, it had a BREEAM “very good” rating and it was open in time for the new school year.

What nobody was keen to draw attention to was that it should have been one of a hundred schools open by next April under the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) programme. When BSF was announced three years ago, the target was to have 100 new schools open by the end of 2007, and 3,500 by 2019. About £3bn worth of work was to be commissioned every year. So far only Brunel and six refurbished “quick win” schemes have been completed. Partnerships for Schools (PfS), the body in charge of the programme, admits that only 12 in total will be finished by the end of the financial year.

Last week, PfS said accountant Pricewaterhouse Coopers (PwC) would be conducting a review into how schools were procured. It will look at three aspects of the process – the role of design, how construction and IT fit together and whether the special purpose companies set up to build the schools could be used to deliver wider regeneration.

The news comes as little surprise to anyone who has tried to work within BSF over the past three years. The procurement method has been memorably described by one contractor as “PFI on heat”, or, to change the metaphor, a grinding bureaucratic juggernaut steered by council officials who spend most of their time struggling to read the map. Consortiums persevere because they can win long-term contracts worth nine-figure sums – but if they lose, they squander millions.

‘Ludicrous’ requirements

Reaching financial completion is the culmination of a 10-stage marathon. For the first of the six waves of projects, this has taken more than two years. PfS’ corporate report for 2005/06 aimed for the first three waves to reach completion by April 2008 – this looks unlikely, given that five of the 17 “wave one” councils have yet to close deals, and only one council from the 10 second-wave schemes (Lambeth) has made it to the construction phase. None of the 12 third-wave councils are anywhere near starting work.

Construction firms will welcome PwC’s scrutiny of the design process – this is one of their biggest gripes. The three teams that make it to negotiations (the eighth hurdle) must each prepare detailed plans to RIBA stage D for three schools, each consulting fully with teachers and pupils. The bidding costs are about £2m apiece, and for two of the consortiums, this money is wasted.

“Why do we keep needing to prove we can design schools? It’s ludicrous,” says John Cherrington, Atkins director. “Schools aren’t exactly rocket science; there’s some simple principles, and we don’t deviate from them much. This review basically means that nobody has confidence in the process, and the circumstances haven’t really changed from the beginning.”

Why do we keep needing to prove we can design schools? It’s ludicrous. Schools aren’t exactly rocket science; there’s

some simple principles, and we don’t deviate from them muchJohn Cherrington, Atkins

None of these issues are new. Contractors, architects and headteachers have been pointing to the same problems for more than a year. Critics have long complained of disjointed management from government on BSF. When Tim Byles took over as head of PfS last November (the fourth chief executive in three years) he admitted that BSF’s “overambitious” first projects had not gone to plan. Which prompts the question of why he’s only just commissioned PwC to look into the problems.

In fact, announcing reviews of BSF seems to be part of the government’s annual calendar. Last October, the Department for Education and Schools announced a review, again by PwC to “learn the lessons from BSF so far and use them going forward. We are looking back to see where we have issues and if there is anything we can do better”.

Now PfS has apparently hired the same company to do the same thing – hardly an efficient use of taxpayers’ money, but in keeping with BSF’s record so far.

The government changes its story

The government says the original review was actually “to evaluate the impact of the BSF programme on educational achievement”. A spokesperson for the newly created Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF) says the contract is for three years, and could be extended for another three. “No preliminary findings have yet been released but we aim to in due course.”

What “due course” means in this context is anyone’s guess, but it is no wonder that PwC is finding it difficult to find out what impact BSF has had on educational standards as only the Bristol school and the six “quick win” jobs have been finished. PwC says it is unable to discuss a client brief.

A spokeswoman for PfS says: “We’ve been very open about the fact that there were delays in the early days of the programme against what were overambitious indicative targets. We’ve now introduced a package of reforms designed to address these early delays and as a consequence the pace of delivery has increased significantly and, overall, the programme will be delivered on time and on budget.”

PfS says improvements have been made in the way it manages inexperienced local government clients. It has assessed every council about to enter the programme in waves four to six on their education and procurement strategy, and signed contracts with each setting out their roles regarding resources and dispute resolution.

We’ve been very open about the fact there were delays in the early days of the programme against overambitious targets

Partnerships for Schools

But Peter Clegg of architect Feilden Clegg Bradley says the problem is with the process rather than those carrying it out. “There are schools being built outside BSF. It’s great working for a local authority compared with working for a BSF provider. The process is simplified, and they go through a conventional limited interview process.”

He has some suggestions for further improvements. “We’ve got to avoid the situation where architects are appointed by the competition process, which causes confusion among clients, and a complete waste of time and energy from the architectural profession.

Speaking for the contractors, Mike Peasland, group managing director of Balfour Beatty, also wants a simplified process. “There should be further standardisation of the conditions. Each scheme has the same basic model for procurement,” he says.

The latest review’s focus on how information and communications technology (ICT) is procured for BSF schools is not before time, either. Peasland says this is a particular problem where there is a mix of refurbishment and new build. “There are inconsistencies in different schemes. Some want ICT as part of the scheme, others want it outside the scheme.”

Paul Foster, head of local government and education at EC Harris, agrees. “On the ICT side, the deals are not big enough to attract all the right players. Some that are active in that area are capable, and have the capacity and intelligence to respond, but there are other providers out there who will find the opportunities too small.”

BSF projects are run by local education partnerships (LEPs), which are special purpose companies formed by council and consortium staff. The third target of the review is to examine how these might serve a wider remit for regeneration. This goes down less well with Peasland: “I’m concerned that the focus could be taken away from the prime function of these LEPs, which is to deliver education. There’s so much going on in BSF, so much potential and we’ve yet to see the programme work fully effectively.”

Others feel that the scope of the review should be widened. One PFI specialist, who did not wish to be named, said one project had been delayed because county councils had been unable to deliver sites owing to wrangles over land use.

Amid the confusion surrounding BSF, one thing can be predicted with safety: the mighty brains at Pricewaterhouse Coopers are going to have their work cut out turning it into a sleek deliverer of anything, let alone larger scale regeneration. In fact, if BSF carries on the way it has been, there won’t be much educational achievement for anybody to evaluate, no matter how many reviews are commissioned.

Client and supplier have to go through 10 stages before construction can start. Here they are:

1 Start of project. The “project initiation document” kicks off a game of bureaucratic ping-pong, in which councils produce successive plans and strategies and get each approved by Partnerships for Schools

2 Strategy for Change, part one. Councils outline their “education vision” and explain how it meets ministerial objectives. This replaces the separate strategic business case and education vision that councils in the first three waves had to provide. But they still have to provide …

3 … Strategy for Change, part two. Which has added an extra stage to the process

4 Outline business case. Councils turn their attention to the specifics of their BSF programme

5 Main review approval. Yet more to sign off, before councils can finally …

6 … publish an Official Journal notice …

7 … and invitation to participate in dialogue. Consortiums are chosen for the long list

8 Invitation to continue dialogue, or invitation to negotiate. Three shortlisted consortiums prepare detailed designs for three schools

9 Preferred bidder appointed. This is a relief to the winner, which can then stagger on to …

10 … financial close. Typically, two years will have passed between stages six and 10. Now construction can finally start…

Postscript

For a comprehensive history of BSF log on to www.building.co.uk/archive

No comments yet