Buildings and musical instruments are usually quite easy to tell apart. That was, until David Byrne got his hands on north London’s Roundhouse

Over the years, some great bands have played the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm, north London – Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie, the Rolling Stones. And now, former Talking Heads frontman David Byrne is giving members of the public the chance to do the same thing with his Playing the Building installation.

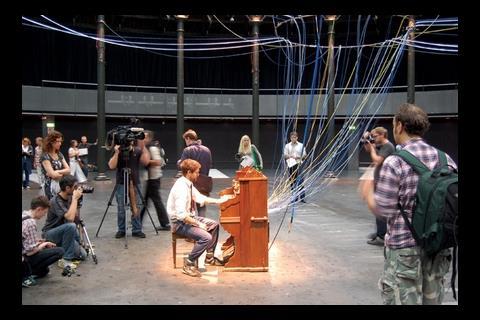

Except Byrne’s proposition is slightly different. Rather than perform dazzling guitar solos, visitors are being invited to play the building itself as a musical instrument. Byrne and his team have wired up an antique pump organ to various parts of the Roundhouse’s structural interior. Blowers force air through electrical conduits and pipes like flutes, oscillating motors cause the girders to vibrate and shudder, and solenoids strike the iron pillars as if they were xylophones, making them clank and chime. The sounds are produced by playing the organ’s keyboard. No microphones or speakers are used – “none of that modern rubbish,” says Byrne – so you know each sound is actually noise coming directly from the building.

Mark McNamara, an artist who acted as project manager for Playing the Building, says the Roundhouse was the ideal structure for this sort of project. “It has lots of steel, perfect cast iron girders, and it is such an impressive space. The fact it has recently had this sensitive renovation means that we were able to hook it all up fairly easily.”

The set-up took two weeks to install, and McNamara said most of this was taken up with testing what sounds could be made from the building’s structure. “We call it fine tuning,” he says. “Drawing out the best sounds we can get.”

Buildings make noise on their own, especially old ones. I remember being woken up in my apartment in New York with the radiators banging

David Byrne

Despite being vibrated, pumped and struck by various small engines, the building is in no danger of being structurally damaged by the installation, says McNamara. “It’s at such a low level that it’s way below tolerance. There’s far more vibration generated during an actual rock concert.”

Byrne himself describes the Roundhouse as the “perfect space” for the installation, which has also been set up in Stockholm and New York. He has rejected other sites before, including an abattoir in New York. “It was more alternative than unique,” he says. “With a building like the Roundhouse, the elements are familar.”

Might Byrne one day build a structure that can be played? He shakes his head. “I prefer to use existing structures. They remind me, and I hope they remind visitors, of what these grand industrial buildings used to be, how they used to sound. Buildings make noise on their own, especially old ones. I remember being woken up in my apartment in New York with the radiators banging.”

So how does it feel to play the Roundhouse? The motors, which vibrate the girders, produce a dark rumbling sound when sustained. If you alternate between the pipes and tinkle the pillars at the same time you can create a sinister cacophony that fills the eaves of the enormous building. But everyone has their own experience of it. Kids, says Byrne, particularly enjoy it. “It’s democratising, in a way, because if you sit down and try to play a Bach cantata you might not make anything that sounds good … or you might do.”

Playing The Building is at the Roundhouse until 31 August

No comments yet