Yes, Building’s backing the campaign to remain in the European Union, but that doesn’t stop architectural correspondent Ike Ijeh having mixed feelings about the standard of the EU administration’s architecture. Here, he takes a whistlestop tour of the most important buildings

European Commission

The European Commission is the dominant powerbase of the EU and essentially acts as the government of Europe. Accordingly, the commission allocates EU spending and crucially, creates EU laws. Important stuff, but the commission’s headquarters, the Berlaymont building in Brussels, is the absolute epitome of what some might term EU blandeur – a hulking, monolithic, 1960s corporate slab that is more business park than governmental seat. By the 1990s, renovation pressure accelerated sharply with the discovery of asbestos and a mammoth refurbishment programme began. A series of disputes, mismanagement and delays transformed the project into one of the longest and most expensive in European history. The principal external change involved a herculean deployment of brises-soleil on the building exterior to regulate solar gain and glare, the first of several EU buildings to elevate the humble shading device to near-messianic status.

European Commission

Brussels, Belgium

Architect (original/renovation) Lucien de Vestel / SA Berlaymont 2000

Contractor SA Berlaymont 2000

Cost €4.82m / €670m

Construction 1963-67 / 1991-2004

Area 240,000m²

Storeys 18

Employees 3,000

UK equivalent 10 Downing Street / Whitehall

European Parliament (permanent)

The permanent seat of the European Parliament is the EU’s only postmodern major administrative headquarters. Known as the Espace Léopold, the parliament occupies a vast complex of several buildings located in central Brussels’ ministerial district, the world’s second-largest government complex after Washington DC.

Dispersed around the gigantic, barrel-vaulted centrepiece block that houses the hemicycle debating chamber, the charmless complex of bland boxes exudes all the sallow charisma of an exhibition centre. The corporate allusions are not entirely accidental; the project was initially privately financed as an international conference centre so as not to inflame French sensibilities keen to protect the legitimacy of the Strasbourg parliament (see next page).

European Parliament (permanent)

Brussels, Belgium

Architect Atelier Espace Léopold

Contractor Atelier Espace Léopold

Cost (1st phase) €1bn+

Construction 1989-1995, 2008

Area 375,000m²

Storeys 17

Workspaces 7,521 (inc. Strasbourg)

UK equivalent Palace of Westminster

European parliament (plenary)

Why have one parliament building when you can have two? This was the question audaciously posed by the French government in 1992. In response, France pulled off arguably the most spectacular diplomatic coup in EU history by insisting to member states that the European parliament could only maintain its administrative base in Brussels if its “official” seat was in France.

Despite only actively being used for 48 days a year, the parliament operates four vast buildings in Strasbourg and the principal one, costing almost £500m, is a painfully vapid architectural exercise.

With its glass hemicycle tower trapped within the obligatory business park cage of brises-soleil, the building bears an unsettling similarity to the upturned drum of a tumble dryer. Things fare little better inside with former parliament president Nicole Fontaine notorious for walking the nine floors up to her office rather than risk the famously recalcitrant lifts.

European Parliament (plenary)

Strasbourg, France

Architect A.S. Architecture-Studio (France)

Contractor S.E.R.S.

Cost €470m

Completed 1999

Area 220,000m²

Storeys 20

Workspaces 7,521 (inc. Brussels)

UK equivalent Palace of Westminster

European Council

Not to be confused with the Council of Europe, the European Council acts as a senior executive committee that negotiates EU treaties and sets the EU’s broader political agenda. While the council does not have the lawmaking or budget dispensing power of the commission, it comprises the heads of government of each member state and is therefore often viewed as the symbolic heart of the EU.

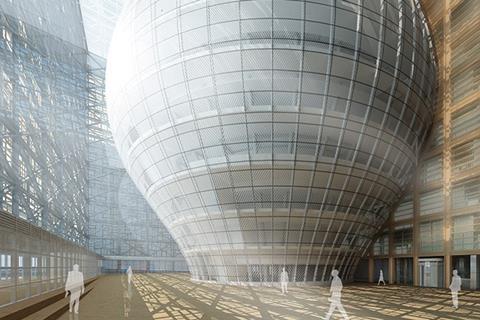

Which goes some way to explaining the concept behind its refurbished Brussels HQ. The 1920s Europa Building’s original L–shape plan has been reconfigured into a cube by adding a wing arranged around a glass atrium. To stress the EU’s diversity, the wing’s windows are constructed from recycled wood from across the continent. But most striking is the giant eight-storey urn suspended within the atrium which houses council conference rooms. Submerged embryonically within an intricate tracery of wood, glass and steel that encase it like capillaries around an organ, the urn is intended to symbolise Europe’s beating heart.

The redeveloped building is undoubtedly one of the EU’s most architecturally interesting headquarters. But opinion of the new building has been sharply divided largely depending on which side of the federalist fence you sit on. Former council president Herman Van Rompuy gushingly compared the structure to a “jewel box that houses the heart of Europe” while David Cameron, at least before his renegotiation conversion, dismissed it as a “gilded cage”.

European Council

Brussels, Belgium

Architect (original / renovation) Michel Polak (Switzerland) / Philippe Samyn (Belgium)

Contractor (renovation) Interbuild-Cegelec

Cost (renovation) €315m

Construction 1922-27 / 2005-16

Area 53,815m²

Storeys 12

Workspaces 3,048

UK equivalent None

European Court of Justice

The enforcer of EU law across the union – the judiciary to the Commission’s executive – is the European Court of Justice (ECJ).

Clearly the ECJ wields immense power. And its new building makes sure you know it. Besides two stalwart, golden 100m towers – the tallest in Luxembourg – lies a vast judicial palace monolithically clad in Corten steel. This contains thousands of offices and smaller courtrooms but the star of the show is the Great Hall of Justice, the most powerful courtroom in Europe. As befits its status, this is a grandiose, symbolically charged space with a giant veil of woven gold steel suspended above the judges’ benches like a glowing consular oracle.

Of course this comes at a huge cost. But the new ECJ achieves a sensuous glamour and poetic resonance that, for EU buildings, is both welcome and rare.

European Court of Justice

Luxembourg City, Luxembourg

Architect Dominique Perrault (France)

Contractor Administration des Batiments Publics of Luxembourg

Cost €500m

Completion 2008

Area 150,000m²

Storeys 25

Workspaces 2,000

UK equivalent UK Supreme Court

European Central Bank

Standing in splendid isolation away from Frankfurt’s superb cluster of skyscrapers, this pair of polygonal towers loom over a vast lobby from which a vortex of atriums surge upwards.

At the summit, the Council Chamber, the ECB’s senatorial inner sanctum, overlooks spectacular city views and is celestially crowned by a serrated, cloud-like ceiling that optically morphs into a map of Europe. The entire building is characterised throughout by swooping diagonals, plunging voids and charging cantilevers, all of which comes as welcome relief from the architectural rigor mortis that normally characterises EU institutional architecture.

European Central Bank

Frankfurt, Germany

Architect Coop_Himmelb(l)au (Austria)

Contractor Ed. Züblin AG

Cost €1.6bn

Construction 2010-2015

Area 184,000m²

Storeys 45

Workspaces 2,900

UK equivalent Bank of England

European Investment Bank

If there’s any EU institution likely to raise something approaching affection from a British audience, then it’s the European Investment Bank (EIB). Not only was its original 1970s building one of the very few Denys Lasdun designed outside England, over the past few decades the EIB has probably part-financed an infrastructure project near you.

In London alone these include Crossrail, the cycle superhighway, Heathrow Terminal 5, the East London line extension, upgrades to Bank and Victoria tube stations, M25 road widening and even the improvement of 38 schools in Croydon. Last year the bank invested a massive £6bn in the UK, just under half of our annual net EU subscription fee. However, unlike the EU budget, which is distributed separately as public spending by the EU Commission, the EIB grants loans, 90% of which are awarded to EU member states.

The EIB’s credentials are further enhanced by its occupation of one of the most environmentally progressive buildings within the EU institutional arsenal. The 170m x 50m tubular lightweight glass and steel building sits next door to the ECJ and is wrapped in a curved diagrid shell that maximises transparency and natural ventilation. A series of landscaped, unheated winter gardens and atriums are also folded underneath the curvature of the roof to act as “climate buffers”. The building’s pioneering climatic concept helped earn it the first BREEAM “very good” certification in continental Europe in 2009.

European Investment Bank

Luxembourg City, Luxembourg

Architect Ingenhoven Architects (Germany)

Contractor CFE / Vinci

Cost €167m

Construction 2002-2008

Area 72,500m²

Storeys 10

Workspaces 750

UK equivalent None

European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) is a completely separate institution to the European Union (and therefore a vote to leave the EU will not affect the UK’s binding legal obligation to comply with ECHR rulings). However, the court enforces the 1950 European Convention of Human Rights, which was established by the Council of Europe. As membership of the council is now a precondition of EU membership, the EU and ECHR, while technically separate, are invested in the same supranational framework.

The Council of Europe was the brainchild of none other than Winston Churchill, conceived as a means to protect democratic freedoms in a war-ravaged post-1945 Europe. So there is a nice symmetry to the fact the ECHR’s Strasbourg base is the only major current EU governmental or judicial institution designed by a British architect.

The building is the first to reveal the three principal democratic themes Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners were to later develop at the Welsh Assembly, and Antwerp and Bordeaux law courts – transparency, spherical forms and natural materials. The ECHR’s distinctive profile comprises three interlocking rotundas, two of which are steel and encase courtrooms and a central glass drum housing the entrance. A further curved, administrative wing extends behind the rotundas, all of which combine to give high-tech industrialism a playfully biomorphic sci-fi twist.

Alas, the wearisome contemporary ruse of glass supposedly symbolising democratic transparency is in evidence, a stunt that might be more convincing were the courtrooms themselves not largely solid.

European Court of Human Rights

Strasbourg, France

Architect Richard Rogers (UK)

Contractor Campenon Bernard SGE

Cost £35m

Construction 1989-1995

Area 28,000m²

Storeys 6

Workspaces 697

UK equivalent None

1 Readers' comment