Three years after completing One St George Wharf in London’s Vauxhall, St George is well on its way to the top of a striking residential skyscraper on the South Bank. Andy Pearson reports on how lessons learned from its last build have shaped the One Blackfriars scheme, and its unusual ‘sky garden’ balconies. Photography by Julian Anderson

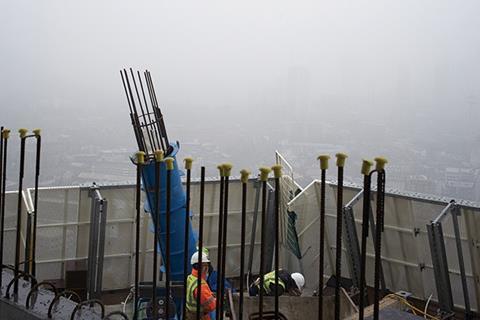

Forty-four floors above London’s Blackfriars Road, 16 operatives are busy pouring concrete and readying the hydraulic jump-form for its next vault skywards, one jump closer to its final destination of floor 50, the top level of developer St George’s One Blackfriars. Designed by architect Ian Simpson, co-founder of SimpsonHaugh & Partners, this distinctive residential tower has already acquired the nickname “The Vase” in recognition of its curved, asymmetrical form. On its completion in early 2018, the tower will be home to 273 private residential flats.

One Blackfriars is the second 50 storey tower to be built by St George in London; the first was the Vauxhall Tower, part of the One St George Wharf, Vauxhall, which completed in January 2014. The developer is using the same construction team, including main contractor Multiplex, on One Blackfriars.

“The founding document for the construction of One Blackfriars included the lessons learned from construction of the tower at St George Wharf, which was compiled with our contractors, consultants and the design team, because that informed the innovations we would introduce on this project,” says Steve Kirwan, construction director at St George. “It is the natural evolution of keeping continuity of people and teams.”

On site, the most obvious manifestation of this is the jump-form rig perched on top of the tower. The tower’s core at St George Wharf was constructed using a slip-form rig. Slip-forming involves pouring concrete into a form continuously moving upwards. It is a very efficient system. However, the problem at Vauxhall was that all site work had to cease at 6pm every day to prevent noise affecting residents living near the site. “It gave us a lot of headaches because we could not run through the night, so the slip-forming became a stop-start process,” says Marcus Blake, managing director of St George City.

It was a similar situation at One Blackfriars with regard to residents and night-working so, instead of a slip-form rig, a hydraulic jump-form is being used. The jump-form allows the tower’s concrete core to be cast in sections, one floor at a time. The rig is also self-climbing so it places less of a demand on crane hook-time; aside from keeping the rig fed with steel reinforcement the crane is free to be used for other activities.

Climbing up

Three floors below the jump-form rig, on level 41, is the first of a procession of trades working up the tower. Here, 60 operatives are installing the concrete floorplate, having cast the perimeter columns earlier. Hidden by the giant climbing perimeter screen wrapped around the top of building, the team is assembling reinforcement prior to the floor slab being cast. The climbing screen extends down four floors to protect operatives and prevent materials from dropping on to the site below. “The climbing screens are one of the key elements in driving the site,” says Blake.

Again, the design of the screen incorporates lessons learned from Vauxhall. “At St George Wharf we had screens that were hoisted upwards mechanically, either by the tower crane or by a mini-crane; here the screens raises itself hydraulically, eliminating the need for crane time,” Blake explains.

The perimeter screen’s diameter can be adjusted using sliding extension panels designed into the screens to avoid gaps occurring between each screen and the building’s curved floorplates. The southern end of the building slopes outwards at an angle of about 7o up to 32nd floor, the level with the largest floorplate. From here, the facade then slopes inward, towards the core, all the way up to the building’s glazed roof.

“Technically, designing the screens to accommodate the curvature and shape of the building was one of the hardest things we’ve engineered on this project,” explains Ian Pratt, project director for Multiplex, the project’s shell and core contractor.

Innovatively, the screens also incorporate a shuttering hoist to allow the aluminium shutters being struck on floor 37 to be whisked up to level 41 for use casting the floorplates, without the need to secure crane hook-time.

Even the shuttering is a more efficient version of the traditional plywood shuttering used at Vauxhall. Here, it is based on a quick-fix aluminium pan system, featuring reusable trays that are locked together from the underside, which improves site safety by eliminating the need for operatives to stand on the deck, and helps speed erection.

The concrete slabs are post-tensioned to keep the floorplates as thin as possible and to prevent the perimeter supporting columns having to be located in odd positions inside apartments. Tensioning takes place as soon as the concrete has reached strength. “We use a thermocouple in the concrete to give us accurate maturity in the concrete in real time, which means we do not have to wait for cube results so we can tension the concrete at the earliest opportunity, allowing us to climb the perimeter screen as quickly as possible,” explains Pratt.

Double-layered

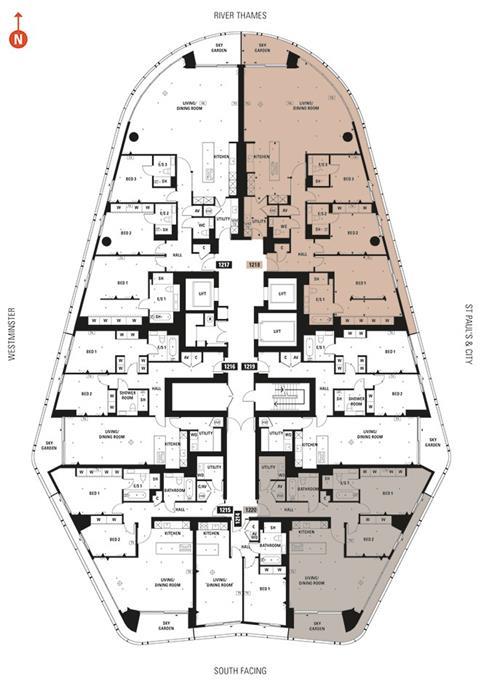

Down 10 more floors and cladding installation is under way. This residential tower is unusual in that it does not have external balconies. Instead, each apartment has what SimpsonHaugh & Partners’ Simpson terms “a sky garden”. This is effectively a balcony sheltered from the elements by the building’s curved single-glazed outer skin. “We hated the idea of balconies hanging off the building, so we used winter gardens,” Simpson says. “We didn’t want to dumb it down by faceting the building, so to create something as organic as this we’ve actually enclosed the winter gardens using curved glass where we needed to.” In contrast to the building’s single-glazed curved outer skin, its inner skin is faceted and double-glazed.

The facade is designed so that the number of cladding panels is the same on each of the building’s floors. The tower’s form, however, means the length and shape of these panels differ considerably. “In total there are 5,400 pieces of glass forming the facade and each one is different,” explains Simpson.

Cladding is delivered from China to site in containers. Each panel is tracked electronically to ensure it is delivered and installed sequentially. Inside the containers, the panels come mounted on stillages, which enables Multiplex to wheel them from the container directly on to the hoist. The hoist delivers the cladding two floors above the floor where it is to be fitted. A spider crane then lowers each panel to the team below for connection to steel channels that have been embedded in the concrete floorplates. “We’re in a great position with the curtain walling: while it has been fitted up to level 32, it has been manufactured and either placed in storage or is on the water on its way to us up to level 46,” says St George’s Blake.

Hoist strategy

As with almost every aspect of this building, the hoist strategy, which ensures cladding can be transported directly from the delivery bay to the work face, is an enhancement of that used at Vauxhall. Three hoists are used – two high-speed passenger/goods hoists, which Blake says are “the fastest in the country”, along with one “mammoth” goods hoist, sized to accommodate the stillages of curtain walling. The hoists are in what Blake terms the “common tower”, which is attached to the outside of the building at the point at which its facade is the flattest.

The common tower was engineered specifically for this project by Multiplex. It was delivered as a bolt-together system. In addition to the three hoists, the common tower also incorporates a secondary escape stair to provide an additional means of escape for the 900 operatives on site and to facilitate the movement of personnel between floors. The tower also accommodates additional toilet facilities, while attached to its outside is the tower’s temporary water supply.

“We used a similar system at the Vauxhall tower, which we have developed and improved for this project,” explains Multiplex’s Pratt.

In addition to the three hoists, vertical transportation is enhanced through the use of two jump lifts. “The lifts help take pressure off the hoists,” says St George’s Blake. The jump lifts use two of the three permanent lift shafts formed in the building’s concrete core by the jump-form as it moves up the building.

The jump lift is created by installing the lift car in the lift shaft. However, because the shaft is still under construction further up the building, the lift motor room is temporarily located near to the top of the completed shaft. As construction progresses the motor room is jumped progressively upwards. “At St George Wharf we had one jump lift, which meant there was some down time while the lift motor room was being jumped – in this tower we’ve got two jump lifts so there is always a lift in operation,” explains Blake.

Fit-out under way

Four floors beneath the cladding installation, the first of the apartment fit-out trades are at work. “The critical path runs through the frame and envelope construction but very soon it will run through the fit-out, so one of the key elements of the whole project is getting the building watertight early and the floors handed over so that fit-out can commence,” Blake explains.

The challenge of making a building that is still under construction watertight is a theme Multiplex’s Pratt mentions: “The building will never be 100% watertight until we put its glass roof on, so the top two floors of the four-floor zone between the cladders and the first of the fit-out teams are used to make the building watertight,” says Pratt. Ensuring the temporary waterproofing is robust is critical to prevent water damage to the fit-out works below. Multiplex even fits temporary drainage to take rainwater down the core and, should the system fail to cope, the contractor has a crew permanently on standby to prevent any problems.

While Multiplex is responsible for construction of the tower’s shell and core, fit-out of the apartments is under control of St George. “A week a floor,” is Blake’s fit-out mantra.

Typically it takes 22 weeks to complete fit-out of a floor. The procession of fit-out contractors is led by the mechanical and electrical contractor with first fix of the high-level services. A week later the M&E contractor will move up a floor so that the drywall contractor can begin its first fix of the walls. A week after that the joinery contractor has commenced work. The procession ends 22 weeks later with a snagging inspection. “We’re working on 22 floors for the fit-out; once a floor has been snagged, we lock up the apartments,” Blake says.

Speedy work

As might be expected, internal fit-out is quicker at One Blackfriars than on the Vauxhall tower, because some of the construction details have been simplified, such as the plaster detailing around the apartment doors. Speed has also been assured through standardisation. Although the floorplates change in size over the building’s height, St George has standardised the layout of the more complicated fit-out elements such as the bathrooms and kitchens by taking up the dimensional changes through varying the size of the apartment’s lounge. “By the time the building’s glass cap is on and the hoist has been struck, we’ll have 150 homes ready for occupation,” says Blake.

The building’s lift strategy has been designed to allow the common tower to be removed as soon as the shell and core works have been completed. This will allow the tower’s first residents to start to move into their new apartments on the lower floors while fit-out continues above. At St George Wharf, the apartments are served by three equal-sized lifts. At One Blackfriars, one of the lifts is significantly larger. “This will allow us to strike the hoist tower earlier and to use the large lift to carry on the fit-out of the floors above,” says Blake.

Using the lessons learned from its previous tower project has clearly enabled St George to build One Blackfriars more quickly, safely and efficiently.

Project team

Developer St George

Architect SimpsonHaugh & Partners

Structural engineer WSP

MEP engineer Hoare Lea

Cost management Aecom

Space planning SimpsonHaugh & Partners

D&B contractorMultiplex

No comments yet