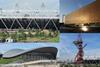

Project bank accounts and project insurances were pioneered six years ago, but few have adopted them. Will the 2012 Olympics prove the catalyst for permanent change?

The government published the 2012 Construction Commitments in July. Collaboration is a key driver of the commitments, which make a series of best practice policies obligatory on all Olympics contracts, including project bank accounts and project insurances.

The public sector has been leading the drive for best practice for some time. Successive initiatives and reports from Latham, Egan and most lately Lord Rogers have championed collaboration.

The Olympics offers the sort of catalyst the industry needs to really embrace it and make it work. Indeed Tessa Jowell, the Olympics minister, has pledged to make the 2012 commitments the norm for all public sector projects.

Collaboration is all about relationships, building teams, establishing an environment of trust, openness and honesty. All these softer issues have a very important role to play in successful collaborative working.

But two more fundamental issues underpin its success – fair payments down the supply chain and abolition of the blame game when things go wrong.

Project bank accounts (PBAs) and project insurances were pioneered as tools to establish true collaboration on Defence Estates’ North site prime contract at Andover, Hampshire, six years ago. Despite this, few have adopted them. But adopt them they must.

How can a contractor’s supply chain ever truly collaborate if it has a festering grievance that it isn’t being paid in a timely manner despite offering a good service?

PBAs are open, transparent and auditable and provide suppliers with the surety of timely payment. Their trust status also safeguards the supply chain’s money should the contractor or client become insolvent.

They have been heralded by the National Audit Office and Office of Government Commerce as a great innovation in the drive for fair payments.

Cynics say main contractors dislike them as they will see them as a further erosion of their margins. They can still benefit from their supply chain’s money, albeit less in these post-Construction Act days.

But margins need not be threatened. Any adjustment in the contractor’s margin to compensate for PBA should be offset by reduced supply chain prices as the need to price the risk of late payment disappears.

Project insurances are equally fundamental as they tackle the blame culture. Any team can collaborate successfully while things are going well. But team working soon grinds to a halt when problems arise and everyone has to dust off their all risks or PI insurance policies to fight a potential claim.

Project insurance covers the whole supply chain and if structured correctly has no subrogation rights. In other words, they do not let insurers drill down to involve the policies of individual supply chain members in the event of a claim.

Consequently there is no need to apportion blame to make a claim. All that has to be established is that a qualifying event has occurred. The team’s focus remains on the project rather than protecting individual positions.

The adoption of project insurances has had marginally greater success than PBAs, the biggest success story being their use on T5 at Heathrow.

A possible reason for the generally slow take-up by the industry since Andover is that Bucknall Austin was a consultant unusually acting as prime contractor on the project. As a result it did not have the baggage, established practices or vested interest of a traditional main contractor so could create collaboration at all levels in the team. It scored the highest marks ever awarded to a Constructing Excellence case study for innovation and best practice.

The sheer scale of the Olympics could make them the vehicle to champion change. Their biggest legacy could be to force the construction industry to alter its practices and to usher in a golden era of collaboration.

Postscript

Brian Kilgallon is a partner at Bucknall Austin and is project director of Andover North. You can email him at brian.kilgallon@bucknall.com

No comments yet