The changing nature of manufacturing and enterprise means we need to unlock many sites in our cities, integrating industrial estates with surrounding neighbourhoods

Heathrow City (left) Loughbourgh Science and Enterprise Park (right)

For our Heathrow City project, we were fascinated by the idea that logistics would be an ever more visible part of our everyday lives, perhaps even becoming a beautiful spectacle.

Now in London we are witnessing an ever growing expectation that goods will be delivered quicker just at the time when industrial land across the capital is being lost to higher value uses. These two factors are causing developers and local authorities alike to imagine a new role for industrial land. To rethink the shed.

Sheds and the city

Industrial estates have long been thought of like burial grounds or abattoirs - bad neighbours unable to be socialised into the rest of society. Well, that might have been the industrial revolution, but a scratch underneath the surface of what happens in many industrial estates reveals rich ecologies of working and innovating. As industry diversifies, cleans up and in some cases collapses the supply chain from maker to consumer under the one roof, perhaps it is ready for this once blacklisted posse to rejoin our cities as neighbourhood assets.

We have discovered in our research for the Loughborough Science and Enterprise Park masterplan that sheds are not what they used to be. Companies operating at scale can often be combining research and development facilities, administrative functions, small batch prototyping and stock storage all under the one (large) roof. The planning use classes order could do with some updating. B9 anyone?

A key challenge is how to allow an organically grown cluster of businesses to continue to thrive while making space for a modern stock of warehouse and employment space fit for the 21st century

Up and down the country, industrial parks can sometimes reveal surprisingly rich ecologies of enterprise and collaboration. No better example of this is at Park Royal, London’s powerhouse industrial district in the north west of the city which contains, as well as manufacturing and logistics, a wealth of food businesses, film studios, metal workshops, jewellers, breweries and technology companies. There are more people working for SMEs than not. Many of these kinds of enterprise wouldn’t be unwelcome in a new neighbourhood, particularly when there are jobs on offer.

Well as luck would have it, Old Oak Common is coming alive next door with a truly awesome regeneration opportunity comprising 25,000 homes, a new commercial centre and three new rail stations connecting it into the London organism.

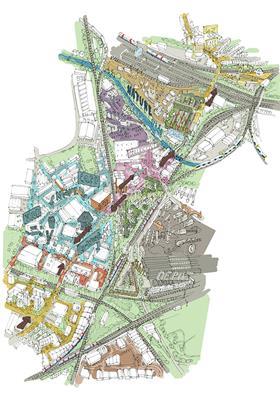

Between Old Oak Common and Park Royal is a curious sliver of land along Victoria Road, where we are currently undertaking a masterplan for the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation (OPDC), with our friends from Peter Brett Associates and We Made That. The Victoria Road masterplan outlines the main themes of the regeneration to come next door: canal, HS2 work site, housing conservation area, new build residential towers, rail cuttings, 1980s housing estates, and importantly a rich mix of commercial, light industrial and warehousing uses, some the oldest at Park Royal.

Here we are identifying opportunities and proposing development typologies that allow industrial sites to intensify their offer as well as integrate with their emerging surroundings. A key challenge is how to allow an organically grown cluster of businesses to continue to thrive while making space for a modern stock of warehouse and employment space fit for the 21st century. An approach to industrial development that makes space for diverse workspaces will enable the unlocking of many sites around London, making the city both liveable and industrious.

The connectedness that rail infrastructure brings to places like Park Royal is a double edged sword, for it provides both a rationale for intensification and also carves up potential development land. We have been dealing with another such knot caused by the convergence of train lines at Loughborough Junction in Lambeth, south London. Here, rail alignments and viaducts form a rich microcosm of spaces that have been the perfect retreat for local enterprises including a boxing gym, cinema club and arts gallery, as well as protected industrial land.

It is this last category that as well as being vital to the neighbourhood in its current form, is playing host to some tentative and very exciting steps to incorporate affordable workspace and urban farming. The diversification of industrial, and the recognition of the changing nature of manufacturing and enterprise is causing a rapid rethink of industrial land making it a better fit in urban locations than once might have seemed.

Logics of Logistics

What are the operational limits of bringing physical goods to consumers’ doorsteps on a mass scale? Amazon Prime hubs are bringing distribution centres closer to the city centre. Last year they opened one such fulfillment centre on East 47th Street in Manhattan, with orders ‘fulfilled’ within an hour of clicking by means of vans, cyclists and even couriers on foot taking the subway.

I’m sure there are many developers sniffing an opportunity to stack housing above a clean warehouse and deliver both on employment space and company bottom lines

These kinds of business innovations find efficiencies in exploiting spare capacity. But what are the consequences for urban development? Will local distribution centres now be a fixture on our declining high streets? What uses could co-locate and piggy back off the Amazon juggernaut? And I’m sure there are many developers sniffing an opportunity to stack housing above a clean warehouse and deliver both on employment space and company bottom lines.

London’s Un-dustrial Revolution

While industrial estates come in many shapes and sizes, much activity goes on in them that doesn’t actually fit inside a lay or even a town planning understanding of “industrial”. How we define industrial land is essential to how we define our objectives for it. If it is intensification, then do we do that by adding more density to what’s there? Do we broaden the kinds of employment uses to make better workplace ecologies? Or do we allow non-employment uses to promote continuity with adjacent mixed uses areas? And if we want activities to diversify, are local authorities and developers properly tooled for the task?

The GLA has documented a 16% decrease in industrial land over the last 15 years. This is leading to an ever more stringent safeguarding of strategic industrial land in the capital. The growing population of London is ever more demanding of timely delivered goods as one of the expectations of modern life.

Meanwhile once peripheral sites like Park Royal are being subsumed into the metropolis and asked whether they will be sociable with their new neighbours. The convergence of these forces exacerbates the need to make industrial land work harder.

In the urban age, this only stands a chance when an approach to developing industrial land goes beyond the estate boundaries and integrates into the fabric of the city.

Darryl Chen is partner and urban designer at Hawkins Brown

No comments yet