In a changing landscape for major sporting infrastructure schemes, what does it take to develop and operate stadiums and arenas? Hein le Roux and Eugene Corrigan of Aecom report

01 / Introduction

More is demanded from modern stadiums than ever before. Designers must interpret and link the needs of fans, the latest standards, aspirations of clients and understand the design elements that drive revenue. The 2014 World Cup stadium developments have not been without problems. Nevertheless, they serve as an important reminder of the complexity in designing, planning and constructing stadiums - particularly when it comes to safety. Looking back 20 years, plainly much has changed - some may recall Lord Justice Taylor’s report of the inquiry into the Hillsborough Stadium Disaster, which recommended that all top-tier stadiums should be converted to all-seated stadiums by 1994.This recommendation was enforced and as a result the majority of stadiums in the UK are in relatively good condition and are, in the most part, safe. However, times have changed once more. Despite the stadiums themselves being in good condition and continuing to operate as home stadiums, the expectations of fans have changed leading to the introduction of new challenges for clubs.

02 / Design considerations

Every club, every stadium has a long list of valuable assets: a loyal fan base and brand reputation to name two. However, not all clubs use these assets to their fullest potential and the development or redevelopment of a stadium or arena is, as a result, complex - with the need to develop an asset that can:

- Drive revenue;

- Be an icon within the community;

- Represent the community and all it stands for;

- Be maintained affordably;

- Comply with safety, licensing and regulatory bodies;

- Ultimately pay for itself.

Designers play a key role in interpreting these issues appropriately such that the stadium evolves from the ground up, or, in the case of redevelopment, from an existing asset into an enhanced one. Developers must understand their operating environment and recognise the various constraints, whether positive or negative, that exist within their organisations, or which may arrive from external factors. A balanced and complementary approach is therefore required to manage these competing issues.

Access to finance is essential - whether through the operator (the tenant or local sports club) or ultimate owner (this might be a consortium, sovereign wealth fund, individual) - to enable major upgrades and also to maintain and operate the building. Pre-1990 stadiums may have already been remodelled to greater or lesser degrees during the nineties, though it is likely that significant remedial work would now be required if further development was undertaken. The requirement to improve or enhance existing facilities is often sufficient motivation to undertake a development - providing revenue gains are achieved for a reasonable cost. Our cost model suggests that remedial work, including works in cutting back adjacent roofs, asbestos removal and reinforced concrete repairs, could be in the order of £600,000. This is a significant addition to the overall budget and a key cost driver, particularly where the design element is linked to existing seats.

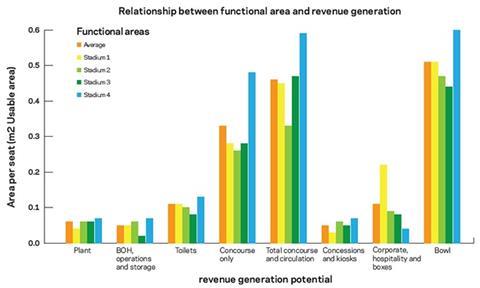

Certainty in having the appropriate budget and knowledge of the cost drivers is essential, but a robust business case does not only depend on capital costs. Understanding the subtleties of the design, and the influence this has on the ability of the stadium to generate the right type of revenue is critical. It is often the elements of cost that have a relatively small impact on the overall budget, have the greatest impact on the functionality of the building, and therefore its operational efficiency and influence on revenue. The chart below highlights space requirements of functional areas and the value they drive.

Useable areas, such as concessions and kiosks, which only require a small amount of space (0.05m2 usable area per seat), are capable of generating a large amount of revenue compared to concourses (0.50m2 usable area per seat), which are more space-hungry yet generate little or no revenue. Two options exist to address this design and revenue equation: (i) make these spaces, such as plant, concourses, back of house and the WCs as cheap as possible or (ii) explore opportunities to allow some of these spaces to generate revenue. Understanding the sensitivity of changes to overall cost and revenue at a particular point in the design is also important. These factors in each stadium and corresponding variation often mean there are unique design, cost and revenue considerations on any stadium redevelopment.

Redevelopment may reduce opportunity cost, but mitigating seat loss is a key consideration.

The advantages arising from redevelopment versus new build are difficult to define. One of the potentially salient advantages of redevelopment over new build are the demands, or design and operational standards, to which new construction must comply, for example row depths and tread. In most cases, increasing row depths and seat widths (particularly in corporate locations) of stadium terracing dramatically reduces the overall number of seats. This may prove to be counterproductive when the primary reason for redevelopment is often to increase capacity. In our cost model, we have identified an allowance in the order of £1m for re-profiling approximately 9,000 existing seats given modern standards.

03 / Cost / function / revenue

Cost drivers in stadiums today are in many instances the same as they were 10 years ago - however, what’s changed is the emphasis on the aspects of design, build costs and derived value. Nowadays it is critical to understand the revenue potential that can be derived through capital expenditure.

Traditional cost drivers include:

- Location

- Capacity

- Type of roof

- Size

- Tier arrangement

While these factors are critical in relation to buildability, overall capital cost and programme, it is their evolution that must be considered in a new cost and revenue environment. The relationship between, cost, function and revenue is sensitive to differential changes in each of these issues. For example, adding additional rows of general admission seats at the back of the upper tier may appear to be a lower cost option, but only if the impact on the roof, terrace and frame is within a particular threshold. If not, there is potentially an exponential step change in cost, although revenue remains constant.

While cost modelling can address the impact of most design changes at an early stage, the impact on revenue and operating costs are also essential aspects that owners and operators need to understand. Aecom’s new Stadium and Arena Investment Tool (SAINT) enables detailed analysis of these interdependent relationships.

Stadium operations are not only about maintenance regimes and life cycle, they should aim to generate the maximum possible revenue from all possible operational and income streams. Stadium development is therefore usually necessary to achieve this objective.

Revenue generated by stadiums can be split into three groups: matchday, non-matchday and season. Matchday revenue accounts for all of the revenue generated when the stadium is hosting a fixture. This includes tickets, food and beverages sales, and merchandise sales. Season accounts for revenue generated by the season tickets. Non-matchday revenue is where the majority of stadiums fail to reach their full income potential. Many clubs are opting to expand and open their stadiums for non-matchday events. Stadium tours, conference centres, retail units, exhibition spaces and concerts are all examples of broader services offered from the stadium asset. The benefits of this additional revenue enables the stadium to become more than just a venue to host the club’s fixtures.

To guarantee revenue from non-Premier League games, such as the Uefa Champions League, the stadium must also abide by the standards set out by Uefa. These include pitch size, players’ facilities and hospitality. Typically, Premier League games are priced on an A, B, C scale - ‘A’ games include derby fixtures, or matches against long-term rivals and other top flight teams. The average split of these games is generally 6:7:5 and the inclusion of Uefa Champions League games can account for up to five additional ‘A’ games.

The demands of today’s players have raised expectations too, and stadiums need to make adequate provision for the latest playing requirements and facilities. Inevitably, total renovation becomes a key consideration, especially where a step-change in club facilities is required. Aecom’s cost model suggests provision in the order of £2m, but depending on the size, arrangement of existing space and existing services, and extent of remodeling, this allowance could vary considerably. Providing entirely new facilities is likely to cost significantly more, but is also dependent on the extent and level of required quality.

04 / Building a brand

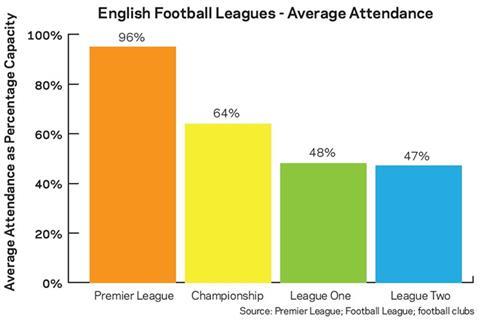

Developing a brand and image is a key aspect of ensuring the success of a venue. However, club operations have an advantage over national facilities because they have an existing regional and club identity. The latest trend in attendance figures show that average attendance for Premier League stadiums is approximately 90%. Stadium capacities vary from 20,000 to 75,000 yet average attendance remains the same. But 90% is not 100%. A building such as a stadium, which generates the majority of its revenue from fans, should strive to have attendance figures of 100% or close to 100%. But there are a number of challenges facing clubs and stadiums in attaining a 100% attendance metric, such as season ticket holders, seats with poor sightlines, unused seats in the away areas and corporate/VIP seats remaining empty. It can be difficult for clubs to determine the right or appropriate mix between General Admission, VIP guests and corporate tickets.

The identity of a stadium, however, and its link to a recognised brand (club or team), and in turn a loyal and constant fan base provides access to other streams of income. Naming rights of stadiums, sponsorship of shirts and training gear are the primary sponsorship deals that clubs negotiate. Smaller deals such as food and beverage sponsorship also supplement these larger commercial agreements. Although these deals are small when compared to the income generated by shirt sponsorship, they do have a large affect on the overall operational costs of a stadium.

Stadium reinvention

A true fan is the biggest asset that a stadium owner or operator could have. However, complacency is no longer an option - stadiums have to reinvent themselves to remain attractive destinations. A primary revenue stream for stadiums is from supporters and fans. This is not only represented in ticket sales but merchandise, food and beverage sales. Clubs and owners should not just look at fans as a source of income because, after all, it is the fans that create the stadium’s atmosphere, and, regardless of league position or team form, provide the stadium with its central purpose. Today’s fans expect an overall stadium experience. They no longer wish to arrive, watch the fixture and leave. They want to embrace the atmosphere of the stadium and enjoy the pre and post-match experience. Stadium facilities are expected to meet or exceed those of rival clubs, and reflect the prices paid for match tickets.

In terms of corresponding capital cost, additional amenities do add cost, but the relative advantages in terms of revenue uplift must be considered. The cost model highlights that the catering (kitchens, concession, bars, associated servicing, etc) element alone contributes approximately £4m - which relates to circa £220/head or seat. Over an average season this equates to under £11 per match.

Programme and procurement considerations

Redevelopment schemes bring added complexity compared to new-stadium construction and understanding these programme constraints is essential to the successful delivery of any project. Furthermore, it is not just construction issues that must be addressed. Often there is an imperative to ensure any new design is integrated into the history of the club and, in so doing, gain its acceptance with the club’s loyal fan base.

Benefits to the wider community

Stadium development or redevelopment also offers a number of benefits to the wider community. Because of Section 106 agreements, clubs are now required under planning to give back to the local community, generally in the form of improvements to the local areas. Local businesses benefit from stadium development, too, as the opportunity exists to sell to a larger match-going market. In reference to Section 106 it is worth bearing in mind the extent of negotiations and consultations that individual developers need to undertake in order to determine such costs. Successful stadiums are seen as integral to regeneration frameworks given their ability to attract business and individuals to a location - they become destinations in their own right.

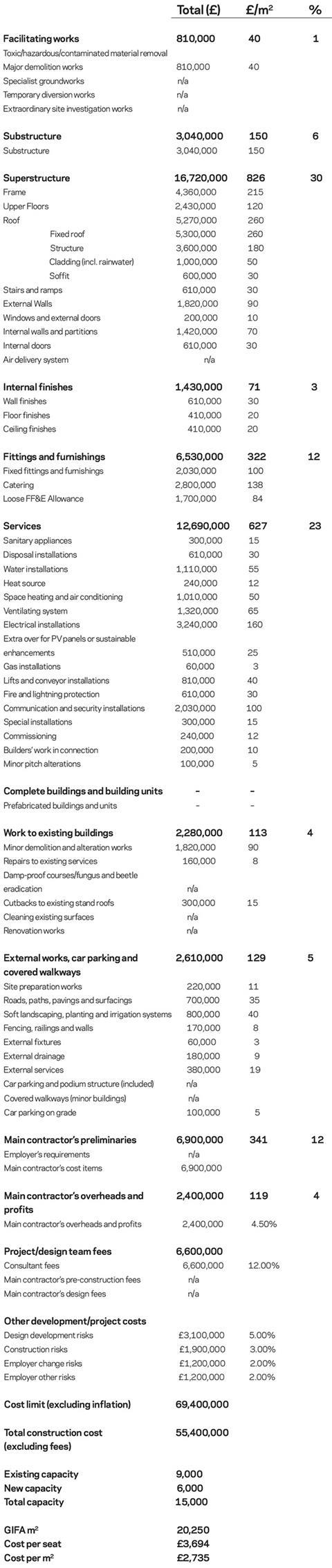

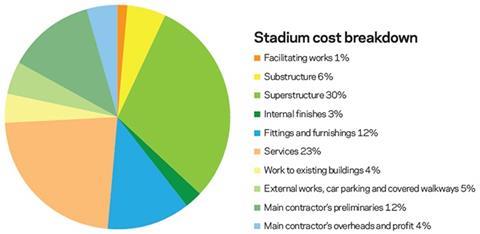

05 / Supply chain restrictions

The demand for new build stadiums has declined in the UK, with the majority of clubs instead choosing to redevelop their existing facilities. Since the Emirates Stadium opened in 2006, Cardiff City Stadium has been the only new build Premier League stadium constructed in the UK. In that time only four Premier League stadium redevelopments were undertaken. This decline has presented a number of problems for clients, one of which is reduced competition in the marketplace amongst constructors. Knock-on effects introduce additional commercial complexities. Where this is a factor, higher than expected tender prices because of constrained supply chains are not to be unexpected, particularly on complex structural or M&E elements. The attached cost model highlights the significant costs associated with these construction elements, which account for 9% and 23% respectively (excluding provision for photovoltaic panels, which could cost in the order of £250/m2 or £1,750/KWp). It is worth noting that the 9% associated with the roof accounts for one third of the superstructure cost.

Further, maintaining a live environment and mitigating seat loss is fundamental to delivery, but this introduces procurement complexity, as this limits the size of the contractor pool able to deliver a scheme with such construction requirements. Constructors with limited experience of stadium projects are often less equipped to manage the stringent programme demands that stadium construction presents. Often a narrow timeframe exists when stadiums can be redeveloped without leading to seat and revenue loss. The close season in the UK is roughly 12 weeks, depending on competitions and corporate commitments to host friendly events. Careful planning and communication between all stakeholders is therefore essential. Where more than one stand is being redeveloped, phasing the work should be explored. Alternatively, work can progress on two stands simultaneously, depending on the impacts to access and existing operations. The cost model suggests the level of preliminaries allowance required is in the order of 15%-16% for a redevelopment project, given the extent of phasing, out-of-sequence working, partial possession requirements, obligations to make safe for match days (during a league season), temporary access, and other ad hoc requirements relating to safety or logistics. Typically, a scheme of this nature is likely to span two closed seasons, and an overall timeframe of at least 18 to 20 months is expected.

06 / Unlocking the Financial potential of a project

The progression of cost modelling through the integration of design tools like BIM is invaluable, but integrated financial models that bring together operational, programme and cost data, such that design can be informed, are more powerful and change the way stadiums and arenas are developed. Aecom’s SAINT (Stadium and Arena Investment Tool), does just this: allowing the client to fully understand the potential of their stadium development or redevelopment at the earliest possible stage. It takes into account all the different fundamental aspects of stadium development, as discussed above, and understands how they are all linked, enabling the client to gain a clear and concise picture of the stadium they both want and need.

Based on some initial design parameters in accordance with very wide development objectives (overall capacity, for example), SAINT begins by determining the potential construction cost of a stadium based on the client’s requirements, and, in parallel, generates the potential revenue and running cost of the stadium, taking into account the various revenue streams open to the client including match day and non-match day revenue opportunities, food and beverage, retail, sponsorship and media.

Through their integration of design, cost, programme and operational elements, modelling tools are highly sensitive to the various difficulties that stadium redevelopment presents, such as working during the closed season, limited cash flow and the stringent standards that stadiums have to abide by including The Green Guide and both Uefa and Fifa standards.

This financial model allows a client to control their project, producing a detailed financial appraisal which brings clarity to the complicated dynamics of any stadium. It easily and effectively demonstrates how small changes in the design - a change in number of boxes, change in GA to premium ratio, varying ground conditions, etc - affect both the cost and the revenue of the stadium and ultimately impacts to the scheme’s viability. It allows the client to tailor the design to meet their needs as a business, while benchmarking the results (utilising the global parametric cost data available through Aecom’s international benchmarking and project performance indicator database, Global Unite).

Along with taking construction cost and potential revenue into consideration, it also calculates the payback period of the development, determines loan amounts, interest rates and inflation to ensure the client fully comprehends all of the project requirements.

07 / Cost model

(based on a redevelopment of a corporate/main stand; on a UK stadium at current prices; the existing stand capacity is about 9,000)

No comments yet