A preoccupation with health and fitness is no longer just for Januarys, it is becoming ever present in day-to-day life, including in the way buildings are designed and constructed. Here, Lizi Greenhill of Sweett Group discusses how spending on a building’s wellbeing performance could be cost efficient in the long-run

01 / Introduction

Did you resolve to be healthier in 2016? The majority of us spend up to 90% of our time indoors, be it at home, in our workplace or in public spaces. All of these buildings create environments for us to operate in, but we do not necessarily consider how these environments might be affecting our health and wellbeing.

Our buildings have a big impact on our level of wellbeing, and the advent of personal fitness trackers and environmental monitors means we are becoming ever more aware of their role.

With a collective 131 million work days, worth around £30bn of GDP, lost to illness each year in the UK, perhaps this year should be the year we resolve for our buildings to do their bit to help us all be healthier and more productive.

Three gadgets that topped 2015 Christmas lists were Nutribullets, spiralizers and activity trackers. The first two claim to help us eat more healthily and the third forms part of the growing “quantified self” movement, which is seeing the tech market flooded with apps, personal trackers and other wearable devices.

These gadgets are allowing us to gain access to previously unavailable data about everything from our heart rate, sleeping pattern and nutrition to air quality and temperature and lighting levels both at home and at work. As we become more aware of the factors impacting our personal health we may begin to expect more from the environments in which we spend the most time.

In the last decade, many developers and landlords have focused on providing energy efficient and environmentally certified buildings. Over the last few years, this focus has turned to how buildings can work harder for the people that occupy them and, more specifically, how these spaces can have a positive impact on our health and wellbeing, as opposed to simply having no negative impact.

Recent studies such as the World Green Building Council (WGBC) report on Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices (the WGBC is due to release a sister report putting the spotlight on retail buildings this February) show the value of addressing this topic and how the right design features and technologies can raise staff productivity within office environments.

02 / What is a healthy building?

The World Health Organisation states: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”

The term “wellbeing” includes an individual’s feelings about themselves in relation to the world or environment, and is the result of a wide range of physical, mental and environmental factors.

A healthy building could be defined as one which creates an environment that not only minimises direct (for example, VOC pollutants) and indirect (for example, poor lighting) impacts on health, but which goes beyond this to work to improve the wellbeing of the occupants helping them to function at their optimum.

Building performance assessment methods such as BREEAM, LEED and SKA already incorporate wellbeing aspects into their criteria and award best practice performance under key issues such as thermal comfort, lighting levels and acoustic comfort. More specifically, the WELL Building Standard, launched in 2014, was developed to measure, certify and monitor the features of the built environment that impact wellbeing.

This performance-based system offers an extensive set of guidelines and standards for designing buildings that aim to make people happier, healthier, and more productive under seven categories: air, water, nourishment, light, fitness, comfort and mind.

03 / What are the benefits?

Improving individual wellbeing can only be a good thing, but there are also direct benefits for organisations that can help make the business case for investing in measures to improve the quality of building environments. Benefits of a healthier workforce (physically and mentally) include productivity gains, increased employee engagement and perhaps greater company loyalty leading to staff retention and attraction.

The most commonly quantified benefit is productivity. Absence due to illness is a clear factor in productivity. However, the more significant, but harder to quantify, factor is presenteeism – when individuals come to work, but underperform.

In 2013, 131 million work days were lost due to sickness and absences in the UK, with the most common reason being minor illnesses and the most work days lost due to back, neck and muscle pain. The Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices report cites that: “The cost of sickness to the employer is estimated at an average £595/employee/year in the UK, while poor mental health specifically costs UK employers £30bn a year through lost production, recruitment and absence.”

Estimating the productivity benefits of a healthy office are complex and will depend on a range of factors, but research has shown that some of the key variables such as lighting, air quality and encouraging increased physical activity can deliver measurable improvements in both reduced absence and increased output when at work. The Health, Wellbeing and Productivity in Offices report collates a wide range of the current evidence, including:

- That improved air quality can deliver productivity benefits of 8-11%

- A study into the relationship between view quality, daylighting and sick leave indicated that variation in view and daylight explained 6.5% of the variation in sick leave, which was statistically significant

- A study of computer programmers showed that those with views spent 15% more time on their primary task, while equivalent workers without views spent 15% more time talking on the phone or to one another.

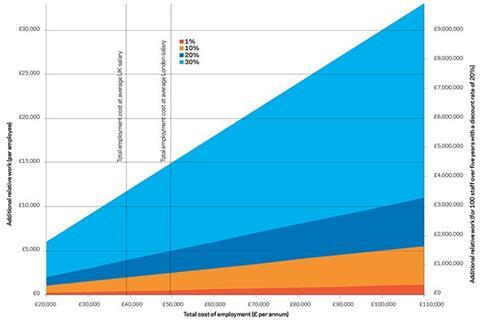

The impacts seen in any individual organisation or office will depend on the current working environment and the nature of the tasks being undertaken. Figure 1 (above) provides a quick reference tool to indicate the scale of financial benefits that might arise if increased productivity or reduced absenteeism is valued in additional days of productive output achieved per year.

The graph shows the annual benefit per employee (left axis) and the aggregate benefit for 100 employees over a five-year lease term with a 20% discount rate (right axis). It must be remembered that any productivity increase is only one dimension of the benefits of a healthy building, but the benefits identified in research studies would deliver substantial financial savings based on improved performance alone.

04 / Developing healthy buildings: opportunities and costs

The benefits of owning or occupying a healthy building are clear. However, the actions required to realise these benefits are less obvious. For new developments and refurbishments, developers need to know what they should be doing to create suitable spaces and environments that can meet current expectations and respond to new research.

It is vital to consider how a development can provide a healthy environment from the outset and ensure that it is communicated to the project team. For shell and core projects major opportunities can come from the structure, building form and core services. For example, maximising daylight entering the building and careful placement of stairwells. With fit-out and refurbishment projects, noticeable opportunities include carefully planned internal layouts, materials selection, fittings and equipment.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all, the opportunities and costs surrounding three aspects contributing to healthy buildings have been explored further. For each of these, the impact on health and wellbeing has been explained, suggestions made for their incorporation and the costs and benefits outlined.

Example 1: Air quality

What is it? – A well ventilated office, with below average levels of indoor pollutants and carbon dioxide can significantly increase occupant cognitive activity and reduce illness absenteeism (for example, from respiratory ailments).

The WELL Building Standard identifies 29 different performance standards for this topic, of which 12 are preconditions for WELL certification.

Impact on wellbeing – Poor ventilation systems can expose users to contaminants, such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and microbial pathogens, which contribute to negative health effects such as asthma and allergies. This in turn can influence productivity.

Incorporating into new buildings – Avoiding pollution sources and providing adequate ventilation and air filtration results in higher indoor air quality. For new buildings this would include, among other things, using materials that do not emit VOCs, achieving strict air quality standards and installing CO2 sensors to help keep the CO2 concentration at an appropriate level (below 800ppm is recommended in the WELL Building Standard).

Close control of sources of external pollution (around air intakes, doorways, and so on) and of potential contaminants from construction processes is important to maintain high standards of indoor air quality.

Costs – Costs will be influenced by the layout of the building and potential sources of external pollution. Higher efficiency filters (MERV=>13) are more expensive than lower rated alternatives but this is not a significant cost item overall. The cost of installing CO2 sensors is likely to be no more than £1/m2.

Benefits – A number of peer reviewed research studies suggest that better indoor air quality (low concentrations of CO2 and pollutants and high ventilation rates) can lead to productivity improvements of 8-11%. Improving air quality can also reduce the risk of minor respiratory illnesses such as coughs and colds, which caused 27 million work days lost in 2013. A 1% to 1.5% decrease in illness absenteeism has been shown as a result of increasing fresh air ventilation rates by 1 l/s per person over the range 2-20 l/s per person.

Example 2: Lighting

What is it? – A healthy office will provide occupants with a view of outdoors, maximise the amount of daylight entering the building and imitate natural changes in daylight properties such as temperature, brightness and colour with electric lighting. Outcomes include reductions in number of sick days and gains in productivity.

Impact on wellbeing – Daylight can have a major influence on our mood and general mental health. It is also the most important natural cue used by our bodies to align our internal body clocks with the 24-hour day cycle, also called the circadian rhythm. Appropriate light cycles are critical in keeping our physiological functions synchronised. When we are out of sync we can experience reduced sleep duration and quality which in turn can increase our risk of minor and major illnesses ranging from catching a cold to diabetes or depression.

Incorporating into new buildings – As well as providing good quality natural daylight and views through layout planning, choice of lighting system can make an important contribution to maintaining suitable circadian rhythms. For example, use of lighting systems capable of varying light temperature, intensity and colour throughout the day can help to replicate cycles of natural daylight.

Costs – The advent of high quality wireless LED lighting systems makes the introduction of circadian lighting a more realistic proposition. While costs are higher than for fluorescent lighting systems, there is relatively little additional cost for colour and intensity adjustable systems in comparison to other quality commercial LED solutions and they have the same excellent life cycle benefits of greater longevity and reduced energy consumption. Wireless controls enable occupancy and daylight adjustments and the introduction of lighting cycles to replicate natural daylight at comparable or lower costs than for traditionally wired control systems.

Benefits – A number of studies have found potential productivity gains as a result of having a view out of the building and good daylighting. A study found that subjects who slept less than six hours a night were more than four times more likely to catch a cold compared with those who got more than seven hours of sleep. A separate study found that those sleeping five hours or less, or 10 hours or more were absent from work five to nine days more each year, as compared to those with optimal sleep.

Example: Physical activity

What is it? – Incorporating active design measures that encourage movement. This can help occupants limit periods of sitting and increase their activity levels during the day. Active design measures include prioritising stairs over lifts, flexible working spaces, access to work stations with adjustable sit-stand desks, locating breakout spaces and printing facilities in a central location and scattered within the main floor plate.

Impact on wellbeing – The physical and mental health benefits from exercise are well documented and physical inactivity is now identified as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality by the World Health Organisation. More specifically, scientists have said that breaking up the working day with bouts of exercise or short movements can help boost employee energy, engagement and efficiency. A study for the NHS found that when compared to those who sat the least, those who sat the most had a 112% increased risk of diabetes and a 147% increase in cardiovascular events. Some research shows that simply standing up after 20 minutes of sitting still is beneficial.

Incorporating into new buildings - Many factors that will encourage activity are linked to space fit out and company policies and culture. However, some core design features are also important, for example, layouts that encourage the use of stairs to go between floors occupied by the same organisation and entrances that make stairs a prominent feature rather than something hidden from view. External works, landscape and masterplanning that encourage walking and cycling are also important.

Costs - The cost of these features will be highly dependent on the building design and should form part of the initial project brief. There may be an impact on net internal areas although effective stairway design can form a valuable design feature in its own right.

Benefits – Active design measures can not only increase employee fitness levels, but also increase the frequency of interacting with other colleagues, encourage knowledge sharing and facilitate networking.

05 / Conclusion

Growing awareness of the impacts of the built environment has resulted in greater demand for ‘healthy buildings’ from key occupiers with prominent developers such as British Land and Lend Lease committing to implementing wellbeing measures within their projects. The benefits of healthy workplaces and the need to attract and retain the best people, make it likely that occupiers will soon see the achievement of wellbeing criteria as being as much a part of the norm for prime space as a minimum BREEAM or EPC rating is today.

We are still at an early stage in developing our understanding of how to deliver buildings that optimise our wellbeing. Although buildings are just one part of the health and wellbeing puzzle, there are practical steps we can take now that will help create better indoor environments and help us all enjoy our hours in the office.

No comments yet