The distribution centre sector is buzzing at the moment, as businesses rush to outsource their goods-handling to logistics firms, and supermarkets adopt just-in-time delivery systems. Here we look at the key issues in affecting distribution centres – and, more importantly, breaks down how much one would cost

Introduction

Distribution and logistics are crucial areas in the manufacturing and retail sectors, providing competing businesses the opportunity to reduce costs and increase the range and availability of goods. Advances in materials handling equipment and technology have made a major contribution to driving forward these efficiencies.

The move by supermarkets and high-street retailers to minimise back-of-house space in stores has transformed the distribution sector, requiring more frequent deliveries of stock, which in turn demands more sophisticated picking and sorting. Efficient distribution systems have also made it possible for supermarkets to move into the convenience store sector without incurring significant cost penalties.

Development opportunities

Demand for distribution capacity has grown dramatically in the UK, fuelled by benign economic conditions, rapid growth in retail spending and fierce competition between manufacturers and retailers to minimise costs. Rationalisation has driven the outsourcing of many distribution functions to third-party logistics companies, often in three- to five-year service contracts. And national retail chains have been consolidating their distribution function into fewer, larger centres and are making greater use of automated materials handling systems.

The result of this trend is that the distribution centre sector has become increasingly polarised between speculative developments of 200,000 ft2 aimed at the contract distribution market, and increasingly bespoke solutions developed specifically to accommodate the systems of large national retailers, typically ranging in size from 500,000 to 750,000 ft2.

In the bespoke market, distribution centres are usually designed from the “inside out” to accommodate the particular storage, picking and sorting requirements of the end user. However, distribution strategies change and layouts need to be flexible enough to accommodate future client operations or to retain value in an open market sale.

A growing constraint upon the development of distribution centres is the availability of land and labour. Based upon institutional development standards, a typical 50,000 m2 scheme requires a site of about 30 acres. Finding sites of this size adjacent to strategic road junctions is increasingly difficult. Furthermore, competition for scarce labour is driving a wages spiral in prime distribution centre locations, threatening to undermine the economies of scale that large distribution parks can bring. In order to counter this trend, operators are investing in high quality facilities such

as gyms to increase employee satisfaction and rates of staff retention. Increasingly, schemes are also being developed in more peripheral, old-industry locations, such as Worksop or Doncaster, where supplies of land and labour are more dependable.

Other factors effecting opportunities for developing distribution centres include:

- Planning. Particular issues include sustainability and job creation issues, visual impact and the effect on adjacent roads and residential areas. Many local authorities do not perceive distribution centres as significant generators of employment. This is not always the case, as some picking and sorting processes can be more labour intensive than modern manufacturing. In addition, the prospect of 24-hour traffic flows and the visual impact of a large distribution centre are also likely to bring the nimby out in some local residents.

Speed of development is a key criteria for the sector, and the ease with which a consent is obtained and its timing can have a significant effect upon the way in which a logistics requirement is met.

- Investor requirements. This is driven by location and labour availability together with the flexibility and long-term market appeal of a development, the length of the lease and the quality of the covenant of the tenant.

- Over the past five years, developers have been encouraged to develop sites with multi-modal transport links between road, rail, and air.

- However, national rail policy has not given freight traffic the necessary financial support to encourage the transfer of capacity away from roads. Although changes to the road distribution environment can be foreseen, including more tolls and congestion charges, together with constraints caused by the enforcement of the European Working Time Directive on drivers, it is likely that most distribution centre activity will remain focused on road transport.

Function and design

Distribution centres are used for a combination of reception, storage, sorting, picking, inspection and despatch activities. The extent of picking and sorting functions required to make up outgoing loads is a major determinant of the layout and configuration of purpose-built distribution centres and the extent and cost of the materials handling system. Although schemes can be highly tailored to the needs of the client, there are only a limited number of generic layouts that are adopted. The main sources of variation between schemes include the number and type of loading bays, the size and arrangement of high-bay storage and the orientation of the structural frame to suit racking. The main generic distribution types are as follows.

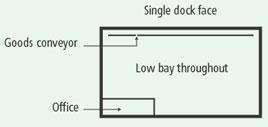

Simple sorting and bulk storage

Low bay units, with a single dock face, are targeted at the third party logistics market. Sorting usually takes place in the receipt and despatch area, and as a result, only sorting of full cases or pallets can be undertaken. Units of up to 25,000 m2 in size are developed speculatively to meet this demand, based on a standard institutional specification.

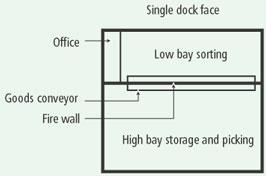

Automated storage and retrieval

These distribution centres have high bay bulk storage areas, up to 20 m high, and with automated materials handling equipment, as well as a low bay picking and sorting area adjacent to a single dock face. The design can be tailored to accommodate the specific requirements of the racking and materials handling equipment. Units with a combination of high and low bay space are typically developed as a pre-let but will need to conform to institutional standards to allow for long-term flexibility to provide security to funders.

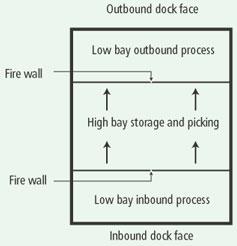

Throughflow

Throughflow distribution centres are distinguished by having dock faces on opposite ends of the building, enabling receipt and despatch functions to be separated. Typically this requirement is driven by complex sorting activities occurring at both sides of the bulk store. Sophisticated materials handling systems associated with throughflow warehouses allow the unit size of goods being picked to be reduced, improving stock control and reducing in-store inventory. Distribution centres designed to a throughflow principle range in size from 25,000 to 75,000 m2 or more. These distribution centres are usually developed as pre-lets or as joint developments between logistics companies and their end-user clients.

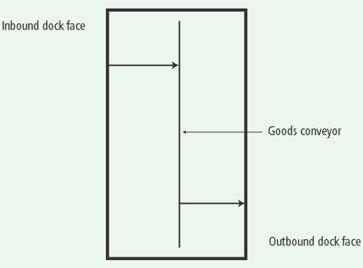

Cross-dock

Cross-dock layouts are highly specialised and are typically only used to provide distribution hubs for parcel delivery companies etc, where speed of transit rather than storage is the main driver. Provision for bulk storage is not usually provided and the scope of materials handling equipment is limited to that needed to facilitate the transfer of goods between vehicles. The main driver behind the size of a cross-deck scheme is the number of loading docks required.

As distribution centres are simple, functional buildings, their key value and cost drivers relate to the size and arrangement of the building.

These include:

- Wall–floor ratio – driven by eaves height generally, layout on plan and the requirements for high bay storage;

- Floor slab specification, including requirements for:

a) floor loading, ranging from 25 to 50 kN/m2 UDL

b) level, vertical tolerances and requirements for applied finishes

c) speed of construction

d) layout of movement joints, corresponding with racking layouts;

- Steel frame design – driven by column centres, overall height, requirements for mezzanine floors and service loadings;

- Fire protection – to minimise end-user insurance premiums – particularly affecting the selection of cladding materials and the capacity of the basic sprinkler infrastructure. In the fit-out, sprinkler systems, fire compartmentation and the provision of duplicate systems are vital to provide disaster recovery capability for the distribution function;

- Modern methods of construction – for example, use of prefabricated components to minimise construction time.

Flexibility and longevity are also important considerations for investors, with envelope performance and building services capacity being key areas that can differentiate buildings by reducing the likelihood of premature obsolescence.

Some developers are beginning to pay greater attention to sustainability and environmental impact issues – specifying, for example, porous paving materials to minimise the impact of large areas of hardstanding on drainage run-off.

Procurement

The distribution centre market is split between the speculative and pre-let markets. Depending upon the requirement for materials handling equipment – and the level of integration of the building works with it – the fit-out, the scope and complexity of work can vary considerably.

In both the speculative and pre-let markets, speed of delivery is crucial. Most requirements come from logistics contracts that have a relatively short lead-in. A programme of 18 months to establish a national distribution network is not uncommon, and many individual distribution centre contracts will have a lead-in of less than six months. Innovation in procurement has been essential for new-build to be able compete with the refit of existing, albeit less-than-ideal, space.

Partnering-based approaches have become common, as large specialist developers such as Gazeley have challenged typical build programmes to be able to accelerate start on site and shorten the critical path. Gazeley’s G-Plan approach guarantees a 12-week delivery programme. Components of this strategy include:

- The use of pre-agreed negotiated rates, rather than competitive tendering;

- The use of an integrated supply chain;

- Parallel design and construction activity

- The appropriate use of modular and off-site manufacture.

- Rapid decision-making is a key element of success and the project team and client’s representative must all have the capability and authority to make decisions so that momentum can be maintained.

- Conventional cost-led design-and-build procurement also has a role in the delivery of both standard speculative distribution centres and bespoke projects, where the end-user and developer will work more closely together to deliver a product tailored to the requirements of the client’s materials handling strategy.

- The distribution process around which the scheme is built and the materials handling equipment that drives the process are the key determinants of the plan and section of a bespoke distribution centre. Materials handling is a specialist discipline and early stage design input is typically provided by a system integrator and installer. Despite this early stage input and the effect that it has upon overall design, the materials handling contract is often procured, at a later date, on the basis of competitive tender.

- An emerging trend in bespoke distribution centre procurement is the direct involvement of end users in the development process. End users are attracted to this process because of the simplicity of the building type, the potential for sale and leaseback based upon their own strong covenant, and the opportunity to reduce costs by taking the developer out of the equation. However, the strength of developers in securing sites and supply chains, and taking development risk is of significant value to occupiers. As a result, “value-sharing” joint ventures between developer and occupier are being adopted as a middle way.

Materials handling equipment

The increasing sophistication of stock control systems and materials handling equipment has been a key driver behind the rationalisation of distribution networks. Systems that were first pioneered by food retailers have become common for even specialist retailers. Current innovations include the growing use of radio-frequency technology in the distribution centre – enabling operatives to work remotely with handheld or cab-mounted computers – and RFID, asset-tracking software based upon the use of unique numerical references for every item of stock. The just-in-time deliveries and minimal on-site storage that modern retail depend upon are made possible by this technology, enabling picking and sorting to take place at very low unit sizes.

The main components of a materials handling system and their primary cost drivers are:

- Racking – overall height and density (determined by aisle width);

- Conveyors – unit size of items being picked, extent of integration with the racking, number of levels within the racking;

- Storage and retrieval systems – degree of automation (forklift vs fully automated storage and retrieval systems, or ASRS), degree of mechanisation, height and density of stacking;

- Picking systems – unit sizes of the items being picked (case/layer/item), extent of automation of picking process, use of remote technology;

- Sorting systems – volume of inventory through the distribution centre, density and diversity of the distribution network being served;

- Warehouse control and warehouse management. Systems for warehouse processes and inventory control – size of distribution centre and extent of warehouse system integration, degree of integration with end-user stock control system.

Indicative costs of material handling systems

Materials handling is a specialist area and costs should be obtained from an established systems integrator. Materials handling systems often include bespoke computer programming of the warehouse control system – introducing a further element of complexity. Given the scale of capital investment, it is important that sufficient flexibility is built into the system to accommodate change in operations without incurring significant penalties. Assessment of materials handling systems on a whole-life-cost basis helps to confirm the optimum rate of return delivered by various configurations. Depending upon the type of materials handling equipment specified, costs of other elements of the fit-out will vary. With “black box” ASRS systems, for example, there is no requirement for general lighting and other services in the ambient bulk store area.

Distribution centre cost breakdown

This cost model features a detailed cost breakdown of a new-build high bay distribution centre with a 15 m haunch height. The costs are based on a generic solution with a gross internal floor area of 70,000 m2, which includes 5% office and ancillary accommodation (3500 m2).

Costs of enhancements including the warehouse and office area fit-out and ancillary buildings, together with costs of external works are detailed. Costs of racking and materials handling installations are excluded. The model has been prepared on the assumption that ground conditions are good and that minimal site preparation is required.

Rates in the model are current at third quarter 2004, based on a tendered design-and-build procurement route, at average UK price levels. Project costs are inclusive of preliminaries, and contingencies. Demolitions, site preparation and remediation, professional fees and VAT are excluded.

Rates in the model may need to be adjusted to take account of specification, site conditions, procurement route and programme. General location factors need to be applied with care to distribution centre projects.

As a high proportion of the value of a distribution centre is focused on nationally procured work such as structural steel, roofing and cladding, costs do not vary to the same degree as for conventional construction.

Reference

Davis Langdon would like to thank Dick Pool, of materials handling systems integrators FKI Logistex, and Howard Penstone, of Davis Langdon’s Distribution Centre Sector Group, for their assistance in the preparation of this article.

No comments yet