If the preparations for London 2012 have sometimes felt like an uphill struggle, at least we haven’t had to ask the world to bring its own food. Launching our Building Memories series from the magazine archive, Building looks back to the Austerity Olympics of 1948 - the last time the Games came to town

Imagine if the 10,500 athletes currently preparing to descend on London for the 2012 Olympics were informed they would have to bring their own towels and food and make their own sports clothes. They might have something to say about it. And it would probably reflect pretty badly on the UK’s ability to stage the event if we resorted to illuminating the running and cycling tracks after dark by merrily circling them with parked cars and whacking the headlights on. Times have moved on then from the last time London hosted the Olympics because, back in 1948, that is exactly what happened.

At first glance, the organisation and eventual staging of the £750,000 1948 Games sounds farcical. The running track at Wembley stadium - the main venue for the event - was a dog track converted by using cinders from coal fires, in the hope that they would bind together to create a hard, even surface. Meanwhile, no one quite knew where to put the boxing arena. It was hastily decided that when the swimming events had finished, scaffolding would be put over the pool and the boxing would take place - rather precariously - on top.

But this was post-war Britain. And the first Olympic Games in 12 years were to be held in a London that, in many areas, had been reduced to rubble. Rationing was in force and many Londoners had been left homeless by the Luftwaffe. Add to that the fact that the organisers had just 18 months to prepare, and it becomes clear that the headline from London’s last effort as an Olympic host should not be the state of the venues but the fact that it managed to stage the event at all.

As the UK prepares to host the 2012 Games against the backdrop of a modern global economic crisis, we launch Building Memories - a trip back through news

stories and images from the magazine’s archives - by looking back at the original Austerity Olympics.

Hard times

In reality, it is hard to sustain direct comparisons between this year’s Games and 1948. The final cost of the 2012 Olympics is expected to come in at £9.3bn. In 1948 the UK couldn’t afford diving boards and was half-starved. Food packages were donated from around the world to try to keep the athletes from passing out during training and events as strict rationing meant they were only allowed 13oz of meat, 6oz of butter, 8oz sugar and one egg a week (the fact that US athletes won the majority of the medals - 84 in total - has often been linked to the fact that they were eating imported steaks). The athletes were transported between 36 venues on old buses and slept in temporary dorms in school classrooms. In terms of austerity, this was the real deal.

It comes as little surprise, therefore, that the public mood surrounding the Games was mixed. Audrey Walker was 21 in 1948 and remembers that they were not at the top of anyone’s list of priorities: “We were all split between focusing on the relief of the war being over and the difficulties of living through rationing,” she says. None of us had cars [so] no one who lived outside of London would have been able to get there easily.”

The average range of enthusiasm for the games stretches from lukewarm to dislike

London Evening Standard, autumn 1947

The newspapers reflected the public’s general exhaustion. The London Evening Standard even suggested, in the lead-up to the Games, that it might be cancelled: “The average range of enthusiasm for the Games stretches from lukewarm to dislike. It is not too late for invitation to be politely withdrawn.” About all we could muster in terms of acknowledging the event was even happening were a welcome sign at Paddington station, and another on the Harrow Road reading “Welcome to the Olympic Games. This road is a danger zone”.

London had originally been awarded the 1944 Games, which were then cancelled because of the war, and then beat Baltimore, Minneapolis, Lausanne, Los Angeles and Philadelphia in March 1946 to host the 1948 Games instead. They were almost handed over to the US due to the UK’s food shortages and financial straits (by 1947, it had exhausted nearly $4bn of US credit).

But Britain ploughed on, with the organisers determined to show that London was up to the task of staging the first Games since Adolf Hitler had opened the Berlin Olympics 12 years earlier. And so it was that, on 29 July 1948, just under 6,000 athletes from 61 nations (Germany and Japan were not invited and the USSR decided to opt out) descended on London to attend the first Olympic opening ceremony in the UK since 1908.

‘An uncleared rubbish dump’

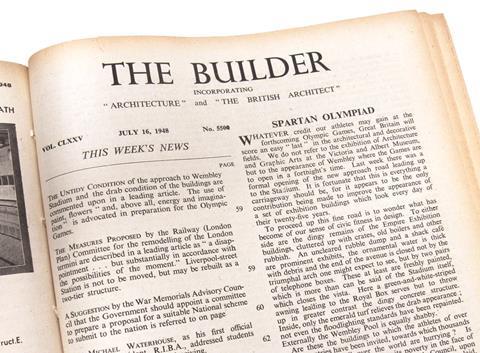

In terms of venues and construction, it seems that our predecessors at The Builder - as Building was then known - weren’t much impressed. In the 16 July 1948 issue, just two weeks before the opening ceremony, a reporter described the rubble-strewn landscape surrounding Wembley: “An uncleared rubbish dump and a shack café are prominent exhibits, the ornamental water is thick with debris and the end of the avenue is closed not by the triumphal arch one might expect to see, but by two pairs of telephone boxes” (full extract below).

Interestingly, The Builder didn’t seem to think that post-war austerity was much of an excuse. The reporter sniffed: “If the Wembley Borough Council … and the Wembley Pool and Stadium authorities can do no better than this, then official action should be taken. … There must be much material from the Royal Wedding decorations that could be pressed into service.”

But while The Builder was putting a lot of faith in the power of bunting, the reality was that there were barely enough resources to provide sufficient sporting equipment: the gymnastics events were supplied by donations from Switzerland, the timber for the basketball court was given by Finland, and Canada sent two Douglas firs for the diving boards.

It is hardly surprising, in this context, that no new venues were built, and those that were used were amended only where absolutely necessary. The organising committee’s budget of £750,000 (about £17m in today’s money) clearly would not stretch to building an Olympic park or village - and there was also the sobering fact that the loss of so many young men in the war had robbed the country of a strong workforce.

Instead, foreign athletes were housed in camps at military bases and colleges around London, while local athletes stayed at home. The central sports ground at Aldershot Command hosted the equestrian events and parts of the modern pentathlon. The National Shooting Centre in Bisley, Surrey staged most of the shooting while Henley-on-Thames was the venue for the rowing competitions. The Herne Hill velodrome in south-east London, built in 1891, hosted track cycling.

‘Dismal johnnies’ …

A very different Olympic build-up, then, to the one we have become used to in London over the last six years. But an announcement in the Radio Times in July 1948 at least gives the impression that, despite the post-war fatigue, the Olympics still had the ability to raise the nation’s spirits. Even if people could not afford to make it to London, they could gather around the wireless and, for the lucky few, television sets. “It is expected that 80,000 people will watch the athletes parade and see the lighting of the torch; but many more will view the scene by television,” the Radio Times reported, adding that commentators would broadcast in 40 languages to audiences throughout the world. Despite everything, the Olympics was a global phenomenon. As Sir Arthur Elvin, the entirely unbiased chairman of Wembley, put it after the event ended (and just possibly with the reporter from The Builder in his sights): “The dismal johnnies who prophesied failure have been put to rout … the 1948 London Games was a fantastic triumph.”

Parading our poverty

The Builder had some harsh words for the 1948 organisers - and little time for excuses …

“Whatever credit our athletes may gain at the forthcoming Olympic Games, Great Britain will score an easy ‘last’ in the architectural and decorative fields. We refer to the appearance of Wembley where the Games are to open in a fortnight’s time. Last week there was a formal opening of the approach road leading up to the Stadium. It is fortunate this is everything a carriageway should be, for it appears to be the only contribution made to improve the appearance of a set of exhibition buildings which look every day of their 25 years.

“To proceed up this fine road is to wonder what has become of our sense of civic fitness in design. To either sides are the dingy remains of the Empire Exhibition buildings, cluttered up with crates, old boilers and other rubbish. An uncleared rubbish dump and a shack café are prominent exhibits, the ornamental water is thick with debris and the end of the avenue is closed not by the triumphal arch one might expect to see, but by two pairs of telephone boxes. These at least are freshly painted, which is more than can be said of the Stadium itself, which closes the vista. Here a green-and-white-striped awning leading to the Royal Box serves but to throw up in greater contrast the dingy concrete structure. Inside, only the emerald turf relieves the drab appearance; not even the floodlighting standards have been repainted. Externally, the Wembley Pool is equally shabby.

“Are these the buildings to which athletes of over sixty countries have been invited, towards which thousands of visitors from all over the world are hurrying? Is Great Britain bent on parading its poverty in the face of the universe? If the Wembley Borough Council, upon whom the responsibility for the approach as been laid, and the Wembley Pool and Stadium authorities can do no better than this, then official action should be taken. A fortnight remains to appoint an architect and to get busy with paint, flowers, with standards and flags and above all, with energy and imagination to rescue something from the gloom. There must be much material from the Royal Wedding decorations that could be pressed into service. Time is short and immediate action is necessary.”

The Builder, 16 July 1948

BUILDING MEMORIES

Building Memories will bring you features and images in print and online of projects from the last century in archived copies of Building magazine, formally The Builder.

To follow Building Memories on Twitter, or to post your own Building Memories please use the hashtag #BLDGmemories

No comments yet