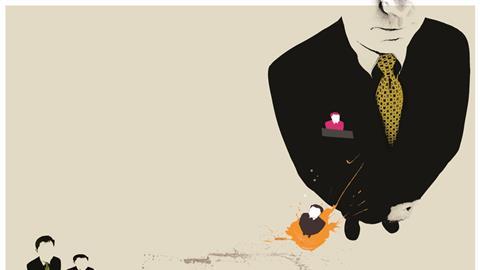

Consolidation is now the name of the consultancy sector game - except some clients still like a more individual touch. Joey Gardiner asks if uneasiness over the new giants is spawning small startups

This week’s overwhelming “yes” vote by EC Harris partners to being taken over by Arcadis was just the latest development in the consultancy sector’s most significant trend: the consolidation of UK independent consultants - QSs, architects and engineers - with global multidisciplinary consulting giants. PwC’s annual survey of global construction merger and acquisition activity, published last week, found that the value of such deals done in the last four quarters was $81.6bn (£51.2bn), a whopping 14% increase on the previous 12 month period. The household names that have fallen prey to these mergers in the last 18 months alone (Davis Langdon, EC Harris, Scott Wilson, Halcrow) represent 395 years of UK construction industry history.

This gradual transformation of a big independent UK industry - one that has exported its expertise to the rest of the world - into a franchise of huge foreign corporates, is a big shift for the sector, emotionally as well as practically. Unsurprisingly, it’s not a change that meets with universal approval, with some clients voicing disquiet about the loss of identity and independence of firms that they’ve been able to rely on in the past. And for individual consultants themselves, this profound change in the ownership structure of UK firms can make a huge difference in their career prospects, making the idea of achieving partner status an ever more distant dream. The expected reaction is a proliferation of start up consultants, formed by experienced QSs from the big UK practices. So is this happening? And if not, why not?

Consolidation

The logic behind the merger decisions of Davis Langdon (an Aecom company), EC Harris and the like is well rehearsed, and the momentum behind this consolidation inexorable. The argument goes that in an increasingly globalised world, the ability for organisations to follow their corporate clients around to the ends of the earth becomes increasingly crucial to their continued success. In other words, the ability to hook a global account for a bank or a Coca Cola or an international mining business becomes dependent on having a credible presence in all the countries your customer works in.

Tiny consultants have certain advantages, and giant consultants do too. In the middle, you may have neither

Brian Kenet, EFCG

Whereas in 2007 the top 10 UK consultants employed a total of 86,100 people worldwide, in Building’s most recent survey, published last month, the top 10 employed 218,800 - over two-and-a-half times as many. At the same time smaller, more boutique practices thrive by keeping low overheads and distinct specialisms. But woe betide those in the middle. Brian Kenet is a principal at an M&A consultant in New York, EFCG, which specialises in the construction industry, and has been involved in deals involving Atkins, Aecom, Arcadis and CH2M Hill. “Consultants have certain distinct advantages when they are tiny, and have certain distinct advantages when they’re giant, but when you’re in the middle you might find, unless you’re very clever, that you have neither.”

Kenet says any firm between 500-5,000 people could now be a target for acquisition. For Hanif Kara, co-founder of AKT II, a specialist engineer that recently separated from ownership by listed firm WYG, the squeezed middle is even larger. He says: “My concern is that anything from 200 to 25,000 staff is the new middle ground. Established and big players are seriously struggling.”

Fears

One problem is that clients aren’t uniformly impressed by consolidations. Philip Youell, chief executive of EC Harris, says the merger with Dutch engineering giant Arcadis is, in part, driven by the needs of global customers for truly global advisers. But that’s not all clients. Others, who have no aim to world domination, worry that bigger consultants may be less responsive to smaller clients, have greater overheads and bureaucracy, and have decision-makers who are hard to reach.

Peter Rogers, director at Stanhope, says the trend is disappointing, and fears that over time a takeover means the culture that attracts the best staff to independent firms may change. “I like smaller companies where you know who you’re dealing with. I want to be able to go to the director or the chief executive when I need to - and not worry that they can’t help me because there’s a board above them governing what they do.”

Danica Farran, a former director at QS Savant, set up independent consultant Equals in 2009 before Savant was bought by Aecom, to avoid being subsumed into a large corporate. The firm has already worked with Land Securities, Oaklands College in Hertfordshire and the FT, with a specific offer based around the London office, cultural and education market. “Particularly in the areas of cost and project management, it is important to have separation from other services,” she says. “Clients seem to be getting more disillusioned.”

I like smaller companies where you know who you’re dealing with. To go to the director and not worry they can’t help because there’s a board governing them

Peter Rogers, Stanhope

However, Bernard Ainsworth, project director on the Shard development for Sellar Group, says he is less worried by an erosion of company culture, and hasn’t noticed a reduction in quality from practices, such as Faithful & Gould taken over by Atkins, that have already lost independence. However, he says: “I would be concerned if I was told I could only get a combined offer, that QS came packaged up with engineering. But so far - with one exception - that hasn’t happened. My relationships are with individuals, not with organisations.”

Career path

If rumour is anything to go by, these individuals at QS practices facing mergers may well be considering their career options. Why? “I could see the writing on the wall,” Farran says. “I wanted to have a degree of control on both our product, and on the interface with the client. I think clients want the personal touch.”

Kenet says: “The biggest obstacle to these deals going ahead is convincing the staff. We’ve seen deals come apart for this reason. Basically, if staff members’ career opportunities are worse, then they will not support it and then there is no way the deal is going to work.”

Engineering and QS firms are traditionally structured as limited liability partnerships, where ambitious staff can aspire to owning a share in the business. Takeovers by larger firms often mean this opportunity is lost. Neill Morrison, a partner in Deloitte, left Davis Langdon to set up a new QS practice within the professional services giant shortly before Aecom’s purchase last year, taking a number of staff with him. “I think the demise of the equity partnership route will become an obstacle to some firms recruiting the best staff. I think an awful lot of ambitious young professionals have felt their career path has been taken away.”

And he’s seen the odd EC Harris CV in recent months, as rumours of the impending merger grew. “We’ve been having a bet in the office as to whether we’ll get more CVs from Davis Langdon or EC Harris,” he says. For Kenet, the fact that consolidation is at the same time provoking the creation of new, bespoke practices, is no surprise. “If you look at other markets that have consolidated,” he says, “you end up with half a dozen global giants, and the stimulation of a flourishing of tiny businesses, from those who for one reason or another decide to strike out on their own.”

Given this disquiet, it has actually been the lack of more start ups to rival Equals and Morrision’s venture at Deloitte that has surprised some. There are a number of reasons for this, not least the toughest downturn for a generation. Richard Jones, owner of QS Jackson Coles, says: “There haven’t been as many of these breakaways as I thought there might have been. The difficulty is that as a new firm you haven’t got the longevity - you haven’t got a track record to show people how serious you are and how long you’ll be around.

“Also, those used to the comfort of a corporate blanket with great facilities, might find it difficult to start from scratch with half a dozen employees in a little office.”

Start-ups could be particularly hamstrung in winning work from larger clients because their funders may require a consultant with a longer track record, or more secure financial covenant, in order to guarantee funding. The client may also require the consultant to take financial risk on the project, which again requires deeper pockets. Morrison said that it was this, partly, which led him to cast his lot with Deloitte after leaving DL, rather than set up on his own: “When I was at Davis Langdon I traded on that name as well as my own. Deloitte has as blue chip a name as any. But if I traded just as Neil Morrison Associates, clients might think, “will I get a grade A team?’”

Unsurprisingly, Jeremy Horner, chief executive at Davis Langdon EMEA, agrees that the actual fallout from consolidation will be limited. “Now is a very difficult time to set up a business,” he says. “But the main reason I think we haven’t seen a lot of these firms setting up is that clients have realised not a lot has changed with consolidation - they’ve still got the same guys working doing the same great job for them.”

Ultimately the official view from within the merged consultants is that the world as we knew it has changed - while multinational customers are increasingly demanding that their consultants are bigger, most other clients are happy to accept the change.

It’s worth remembering that Davis Belfield & Everest’s founder, Owen Davis, railed against the 1988 merger with Langdon Every & Seah that created Davis Langdon Everest, because it was going to create a 300-strong firm that was “far too big”. Times move on. However, for those brave enough to break out from corporate culture and start out on their own, there are still clients willing to reward them.

No comments yet