Pressure is on the Qatari authorities to do something about the working conditions of those building the World Cup 2022 infrastructure and venues, so what are the risks UK companies working there could face?

Last week Fifa president Sepp Blatter was forced to discuss the latest and biggest problem confronting what has become the most controversial World Cup in history.

Qatar 2022 - already hit by allegations of corrupt voting and questions over whether Qatar’s intense summer heat is appropriate for a sports tournament - is now under scrutiny on another front: the rights and safety of the workers building the venues and infrastructure the tiny Gulf state needs to host the World Cup.

Dedicated World Cup construction is yet to begin but the International Trade Union Confederation has warned it could cost the lives of up to 4,000 foreign workers under current practices in its booming construction economy.

Following a meeting of Fifa’s executive committee on Friday, Blatter expressed “sympathy and regret” over recent reports in the Guardian newspaper of high numbers of fatalities among construction workers in Qatar, including the revelation that 44 Nepalese workers died in the country between 4 June and 8 August this year, with more than half of these attributed to workplace accidents or heart attacks. Blatter called on the Qatari authorities to tackle this, but also put the spotlight firmly on European construction firms, “who are responsible for the condition of their employees”.

It is not only the health of workers and the reputations of the companies involved that are at stake. British solicitor Leigh Day is already examining the case for legal action against any UK construction firms found to be working on projects where labour laws are breached, and other lawyers are warning of further liabilities. So what are the risks for UK firms working there? And what action can British contractors and consultants take to protect themselves and the vulnerable individuals at the bottom of the supply chain?

Safety last?

On the face of it there is no financial reason why Qatar should have a poor safety record: it is the richest nation on earth by income per capita. But it also has an ambition to become a major regional power and the sheer rate of its transformation poses problems.

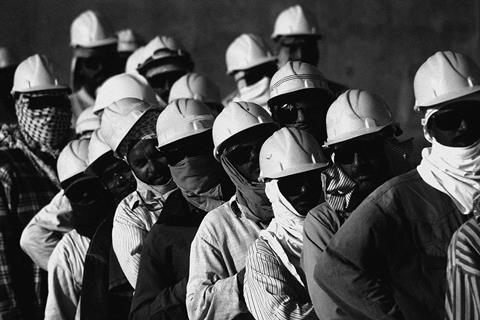

Qatar’s construction economy is forecast to grow faster than any other country - by 10% per year between 2012 and 2025 according to the most recent Construction 2025 report by Global Construction Perspectives and Oxford Economics. It is spending an estimated $100bn (£62bn) of its oil and gas wealth on infrastructure ahead of the World Cup and relies heavily on cheap migrant labour, with workers from some of the world’s poorest countries making up around 1.2m of its overall 1.7m-2m population and a staggering 94% of the entire workforce. Up to a million further foreign construction workers are expected to be recruited in the decade running up to 2022.

![]()

This, coupled with the so called “kafala” system - the nationally ingrained method of organising labour which hands the employer huge power over the worker (see box below) - helps explain a scenario that has been likened to modern day slavery. Combine that with temperatures which can top 50°C and the high fatality rate becomes still easier to understand.

A study carried out by Human Rights Watch (HRW) last year, Building a Better World Cup, found construction workers often lived in squalid conditions, struggled to get their meagre pay on time and in full, and had few means of redress. HRW’s report said the existing system “effectively traps many migrant workers in their jobs”.

“We don’t complain because if we complain for anything, the company will punish us,” one 18-year-old Nepalese worker told HRW.

One British engineer involved in the Qatar World Cup, who did not wish to be named, places most blame on unscrupulous foreign firms from developing countries working there.

“Qatar is actually the one country [in the region] that tries to help - in Abu Dhabi or Oman or Saudi, they’re just not interested in this - but … [the problem is] the Indian or Bangladeshi middle man who does a deal with his government [to bring the workers to Qatar].”

Keith Clarke, the former Atkins chief executive and now an adviser to the Qatari government on planning and infrastructure, stresses that the problems migrants encounter are “exacerbated by the magnitude and rapidity” of Qatar’s “enormous” population growth in the past five years.

“The labour issues are very real … There are [construction] sites I’m familiar with in Qatar which are world class in terms of health and safety but there are others which are not even close.”

Clarke believes there remains a clear economic case for the movement of labour into Qatar from poor countries, despite the risks. He says: “It is inexcusable to not pay people for their work, to not have people coming home after their work. But repatriation of money is unbelievably important. The money being sent home is a lifeline.”

UK firms

Qatar has made some efforts to improve the situation. Its labour laws, updated in 2007, do offer protection to workers but tend to be poorly enforced, according to all those spoken to for this article.

Hence in April this year, the powerful Qatar Foundation introduced a detailed set of mandatory standards for migrant workers on its projects, which go beyond the 2007 laws.

The standards set out by the quasi-governmental foundation - which is also a major construction industry client - cover workers’ welfare, the requirement that workers “receive equal pay for equal work” and a list of ethical principles including outlawing recruitment or placement fees and providing better information for them on what to expect in Qatar before they set out.

Crucially though, responsibility for compliance with the standards - which look likely to be adopted by other major clients in Qatar including Q22, QRail and Ashghal and » » could even become legislation - has been placed not with the client but with the main contractor. This potentially imposes on UK and other overseas construction firms a key enforcement role over issues such as the behaviour of recruitment firms in the worker’s country of origin, even though they may have little practical control over them.

Nick McGeehan, gulf researcher at Human Rights Watch, says: “I think construction firms are in a very awkward position in Qatar. Many cannot afford not to be there but it’s also an unregulated market and that poses reputational risks. What is going on there is pretty horrific and not something a reputable company would want to be involved with.”

What is perhaps even more alarming for such firms is the potential legal risk they face, which may even extend to criminal sanctions, experts are now warning.

Partner in Leigh Day, Daniel Leader, says the firm is examining whether UK-based contractors and project managers working in Qatar have breached the Qatari labour laws.

Though it has yet to launch any cases against British firms, it is offering its services on a conditional fee basis - an essential requirement for impoverished workers and their families.

“Construction firms have a duty to make sure they are operating in a manner compliant with Qatari law and with international labour standards,” Leader says. “They need to be sure of the way they are operating with regard to their own workforce but also be alive to the behaviour of subcontractors.

“Where the company - or a subcontractor - is employing workers who are being abused or exploited, there is potential liability.”

Other lawyers agree that the legal threat is real and growing. Jan Burgess, a partner in CMS Cameron McKenna and a solicitor specialising in health and safety, says cases could be raised against UK-based firms in the London courts based on Qatari law, breach of contract or even English common law.

“We very frequently have [international] cases raised in the UK,” she says. “It’s the law of negligence and the general duty of care, which applies to employees but also to third parties.”

While Burgess believes any compensation awarded would be low because of the wages involved, she advises UK construction firms working in Qatar urgently to check if their insurers would cover such claims.

It remains possible that external pressure on the Qatari government might prompt it to arrest managers of western firms based there under Qatar’s criminal laws, a scenario that could see individuals imprisoned.

“If I was a senior manager working for a firm out in Qatar, I’d be really quite nervous at the moment as this is becoming so highly publicised,” Burgess says.

“We may see some reaction from the authorities and that could be for them to go into big companies and arrest senior managers.”

Action

So what can such firms actually do to improve things given they are working in a largely unfamiliar system for often demanding clients who appear to hold most of the cards? The unnamed engineer says he has resorted to trying to design less technically demanding buildings in the knowledge these will be less dangerous to construct.

But not all feel that UK firms are so powerless. Despite the difficulties, many believe that all foreign firms - and especially Qatar World Cup programme manager CH2M Hill - can make a meaningful difference.

Keith Clarke insists firms can ensure decent conditions for workers, and is contemptuous of those that instead fret about getting sued. “You need to take reasonable measures to make sure people aren’t placed at risk,” he says. “If you are worried about legal action for killing people then the answer is to stop killing people.”

He adds that making sure the supply chain is paid is “fundamental” and believes consultants can play a role by specifying contracts including clauses covering health and safety. “I didn’t say it was easy to influence the client but it can be done and there is no excuse for not trying.”

A number of consultants working in Qatar spoken to by Building say they will raise the issue with their clients to help ensure necessary action is taken. A spokesperson for architect Grimshaw said the firm “will be discussing working conditions with our clients in the region as soon as we can, and reviewing what we, as building designers, can do to help.” Likewise Paul Dollin, executive director at WSP, said the firm would “continue to use our position in the Qatar supply chain to influence high standards of health and safety.”

Further to that, HRW’s McGeehan believes Qatar’s need for UK expertise can be leveraged through collective action to improve conditions that wouldn’t damage individual firms’ commercial position. He says: “I’d like to know whether there has been any collective action on the part of the firms to approach the Qatari government? Of course, that is difficult, so why not approach the UK government and ask it to approach the Qatari government?”

That idea may prove appealing to the firms involved. Given the growing profile of Qatar’s World Cup workers, it seems the only option UK firms can now rule out is to do nothing.

What the firms say

A spokesperson for Arup:

Arup is not a position to comment on the allegations raised. We are legally obliged by the terms of our appointment to refer any and all enquiries related to the Qatar 2022 programme to the client’s representative, CH2M Hill.

However, we are aware of efforts to address the issues noted in the article in The Guardian and understand that the Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee recently reiterated its commitment to the ‘Worker’s Charter’ in response to these stories about workers’ welfare.

As designers we do not employ or award construction contracts in Qatar. Therefore, any comment from us would be uninformed speculation.

Given the points above, I am sure you can understand why we cannot comment on this particular story.

For the record, Arup has clear policies relating to the working conditions for those employed by the firm. In addition, it is Arup policy to ask sub-consultants employed by us to meet ethical standards relating to anti-corruption practices, for example.

Around the globe, Arup is firmly committed to adhering to all the relevant labour, safety and ethical standards wherever the firm is engaged.

A spokesperson for G&T:

Gardiner & Theobald LLP is appointed by the Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee as Cost Consultant on the 2022 FIFA World CupTM Qatar, advising on venues rather than infrastructure projects. At present, the World Cup projects we are appointed on are in the planning stages and have not yet started on-site.

In common with every responsible firm involved with construction we are naturally concerned about safety on construction sites wherever we are appointed.

We will support the Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee as far as possible to ensure the health, safety, well-being and dignity of every worker that contributes to building these venues for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.

A spokesperson for Buro Happold said:

Buro Happold is currently delivering a flagship project in Qatar which works to internationally recognised health and safety standards at a level which is at least comparable to international best practice. Similarly in our work on New Doha International Airport health and safety was a key measure in the delivery process . As an organisation Buro Happold places great significance on health and safety as part of a high quality procurement process, on a par with the many other aspects that we use to measure performance on our projects. Roger Nickells, Managing Director Middle East

A spokesperson for Grimshaw said:

We are involved in projects in Qatar and are disturbed by recent reports in the Guardian, and produced by the ITUC, about the number of construction-related deaths. We will be discussing working conditions with our clients in the region as soon as we can, and reviewing what we, as building designers, can do to help.

A spokesperson for Aecom said:

We, with Zaha Hadid, are the design consultants for Al Wakrah Stadium. Construction of the stadium has yet to commence. Qatar has strict labour, health & safety laws, and the Qatar 2022 Supreme Committee is committed to ensuring these are met. Safety on our projects for our clients and staff is always our number one priority.

A spokesperson from Mace said:

The safety of our people comes first. We seek continual improvement on all projects across the world to create and maintain safe and healthy workplaces. For two decades we’ve worked with our clients, consultants and supply chain to support our vision that it is simply unacceptable for people to get hurt while at work.

Paul Dollin, executive director at WSP, said:

As a global professional services firm in the built environment we regularly interact with the construction industry and as such, take health and safety of anyone who interacts with our work very seriously. Health and safety is as much about corporate culture as it is legislation and while legislation changes from country to country our high standards are set by our global culture, which remains a constant. The conditions referenced in the ITUC’s report are appalling and we will continue to use our position in the Qatar supply chain to influence high standards of health and safety.

A spokesperson for Balfour Beatty said:

Balfour Beatty is not involved in any World Cup construction projects in Qatar.

At Balfour Beatty we take Health & Safety matters extremely seriously. We have clear policies & practices in place to improve safety throughout our business - in any part of our Group, including any partners, subsidiaries or sub-contractors working anywhere in the world on anything we do. Details of these can be found here.

What is the kafala system?

Kafala is a system of sponsorship used to monitor migrants working in Gulf Arab states. It has been criticised by human rights groups for placing workers at the mercy of their employer/sponsor and encouraging abuse.

Typically, a young man from a country such as Nepal, India or Bangladesh pays a hefty fee to a recruitment firm in his home country - meaning he is indebted from the outset.

Human Rights Watch last year interviewed 73 migrant workers and said all but four had paid recruitment fees of £450 to £2,270, borrowing from private lenders at often exorbitant interest rates. On entering Qatar, the worker’s employer - often a foreign company - may also then confiscate his passport.

Over the past few decades, soaring demand for cheap labour in the Gulf states has seen Arab migrant workers gradually replaced by South and South-east Asian migrants. In 2008, Bahrain became the first state in the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) to claim to have banned kafala. However, Human Rights Watch later criticised the authorities for doing “little to enforce compliance”.

No comments yet