With the popularity of global sporting events continuing to grow against a background of economic uncertainty and the need for reducing public expenditure, Hein le Roux of Davis Langdon, an Aecom company, examines the pros and cons of using temporary venues for sporting events

Introduction

Major sporting events occur across the globe every year (Summer Olympics, Winter Olympics, Commonwealth Games, Pan American Games, Fifa World Cup) and bring with them significant benefits; but do these benefits justify the cost? Do major event organisers still believe they must build iconic venues and facilities and will these permanent venues necessarily provide the lasting legacy required? The eyes of the world will be watching, and event organisers must ask themselves if they want to be remembered for iconic facilities, such as Beijing’s Bird’s Nest, or for failing buildings as were seen in some recent events? Alternatively, can a temporary venue provide a better solution, or do they represent a false economy? Is there more to a temporary venue than meets the eye?

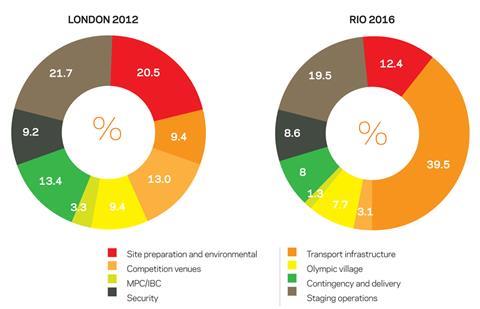

Construction works for major events represent significant capital expenditures, which are primarily funded by governments. For example, the total expected government costs for the London and Rio Games are approximately £8bn and £9bn, respectively.

The pressure is on to reduce the capital expenditure given the current economic climate. Recently, the 2013 Mediterranean Games were re-awarded to the city of Mersin in Turkey, as a result of the financial crisis in Greece.

Tarragona in Spain, the host for the 2017 Games, has already indicated significant investment cuts given the austerity measures in the country. One option is to incorporate the use of temporary venues - a strategy already adopted by London 2012 and Rio 2016.

This article explores the underlying drivers that are pushing organisers towards either permanent or temporary solutions for major events and considers the wider context in which organisers must deliver appropriate solutions.

Catering for size and scale

Mega-events are extremely complex in that they must cater to thousands of people, in a proximal location, while utilising significant areas of land. The land demand is high, with a typical Commonwealth Games or Olympics requiring anything in the order of 200ha to 1,500ha - and that is typically only the main park and athletes village. The Sydney Olympics utilised 640ha, Beijing 1,200ha and the 2012 London Olympic park is 245ha. The proposed main Barra da Tijuca site in Rio de Janeiro, while only 118ha, is only due to host 31 of the 61 Olympic and Paralympic events, meaning an additional three parks are required.

Once a location has been selected and the broad infrastructure requirements determined, one can begin to consider the venues in greater detail. Determining the appropriate combination or ratio of permanent to temporary venues can be a demanding and challenging exercise. In fact it’s more complex when you consider all the potential options for each venue:

1) New permanent

2) Refurbish existing

3) Convert existing

4) Half-permanent/half-temporary

5) All temporary new

6) All temporary existing

7) Part new permanent/part refurbish or convert/part temporary

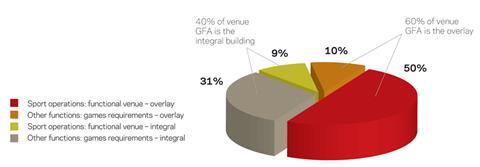

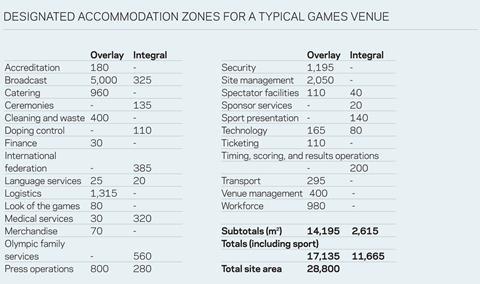

Then there is the overlay, including temporary works to support venues, other temporary facilities specific for the event, other temporary infrastructure and permanent enabling infrastructure. In terms of venues and facilities, the overlay could contribute up to 60% of the games’ total accommodation (gross floor area) requirements and could physically occupy up to 10% of the overall site area. The proposed overlay design for Hambantota in Sri Lanka’s 2018 Commonwealth Games bid occupies in the order of 21ha (or 6%). This, in itself, is an extremely complex arrangement requiring careful planning and analysis. For example, the Commonwealth Games manual advises on 17 varying categories of items required ranging from portable toilets to a complex field of play including space for officials, judges, press and monitoring equipment.

Overlay requirements typically include provisions for sponsors: temporary venues for entertainment, accommodation, food and beverage facilities, parking and VIP facilities, viewing areas, exhibition space, and temporary services like power, water, waste.

Trends in major sporting event growth

Major sporting events like the Olympics have seen significant growth over the years, with sponsorship deals ever increasing in value.

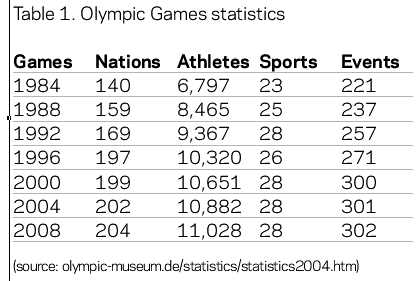

Table 1 summarises this:

It is this growth that underpins the extent to which major events receive media interest and, subsequently, sponsorship funding. According to Dmitry Chernyshenko, chairman of Sochi Olympic Winter Games 2014, the Games has achieved approximately $1.2bn in sponsorship to date, thus exceeding the levels achieved for the Beijing Olympics.

Other major events, like the Fifa World Cup and Uefa Champions League, are equally popular as exemplified by their continuing growth. According to FootBiz, the Uefa Champions League games attracted €179m (£154m) in television rights in the UK alone during the 2009-2010 season. The total across 14 countries amounted to €562m (£484m). Similarly, the 2010 Fifa World Cup attracted revenue of $2.4bn (£1.5bn) through TV rights and drew an average of 49,600 spectators to the 64 matches, according to its financial statements for the period 2007 to 2011.

As major events become more popular, there will be even more pressure on host cities to provide more infrastructure and venues. Thus, the necessary quantity of temporary venues will greatly increase, but host cities will continue to find alternatives to venues that hold little or no legacy prospect.

The Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympics illustrates a possible trend; on the Barra da Tijuca site, of the 14 competition venues (excluding the practice field of play, the International Broadcasting Centre and the Media Press Centre) at least five will be temporary and two or three existing venues will be refurbished, meaning there will only be six completely new venues. Of the new venues and refurbished ones, all will feature prominently as part of a proposed Olympic Training Centre, developed as part of the legacy vision.

Event vision versus legacy vision

A key objective for the host city and country is to align the vision for a mega-event with the country, region or city’s long-term needs and objectives. In other words, establish if there is an ultimate legacy requirement that will take priority. This legacy need could stem from a myriad issues.

Taking Rio 2016 as an example, the Olympic Training Centre is a key part of Brazil’s sports development strategy and national pride, as it will provide high-performance training facilities for athletes. Additionally, venues such as these can be used to address national health issues, such as obesity or alcoholism.

There may be a desire to kickstart the regeneration of an area, as is the case in London 2012, or a plan to create an academy to improve medal standings.

Assuming various requirements can be articulated and aligned with the necessary venues and facilities, there are questions to be asked, including: does the business case exist and can it be financed? Can it be packaged in a way so that it will become mainstream (if not, it won’t become a catalyst for change)? Will the community support it? Specialised sport venues may provide great legacy in theory, but if the sports they are intended to host are not indigenous, why would local people use them after the event?

If none of these questions can be answered positively, should this lead to a temporary solution being sought rather than a permanent one?

At the recent International Olympic Committee (IOC) meeting in Lausanne, Switzerland, Sebastian Coe, head of London’s organising committee for the 2012 Olympic Games, offered his advice on avoiding such “white elephant” facilities to the 2020 prospective host cities, stating: “The legacy thinking has to be enshrined in the beginning. Where legacy is a problem, it is because it has been an afterthought.” Thus host cities must carefully consider what to do with the venues, infrastructure and facilities after the Games.

With this in mind, to what extent could a temporary venue be dismantled and recycled? This is a great notion in theory and, while a facility may have to be downscaled to reduce its cost and complexity, is technically possible. However, there is a threshold at which a venue’s design is driven by the demands of the event itself.

Consider a stadium hosting the Fifa World Cup final. Historically, the overriding requirement is a venue with a minimum capacity for 60,000 spectators. Larger venues have not been discouraged, such as Berlin (74,500) or Soccer City Johannesburg (94,700). Similarly, the Commonwealth Games requires seating for 40,000 for athletics and ceremonies.

At this scale, it becomes increasingly difficult to create “temporary” elements that can a) fulfil structural demands; b) still be more cost efficient in terms of material, labour, manufacturing, transportation and installation than a permanent version; and c) remain sufficiently modular and/or generic to have a market value post-Games. Without adjustment to the events’ demands, it is unlikely that smaller venues will be acceptable in the short term.

However, perhaps a shift is possible - the latest edition of Fifa’s technical recommendations and requirements does not state minimum capacities, but includes statements like: “Capacities should be decided after discussion with the legacy stadium management to project event seating potential.” It also states: “There are no known formulas for determining a stadium’s optimum capacity. It is a choice for those in charge of its development.”

Fifa also supports modularity. Green Point stadium in Cape Town had 68,000 seats during the World Cup - it was meant to downscale to 55,000 in legacy, which has not yet happened. On this basis, is it naive to think that a country could actually provide demountable venues that get shipped to emerging nations after an event?

Perhaps not, but one has to consider the overall context too - how does one get the millions of people to and from the events?

Infrastructure and transport

Major events require extensive investment in infrastructure and transportation, which is vital to their success. For certain events these surpass all other requirements. Nevertheless, one must not forget that the venues remain the destination - and are the drivers of the subsequent development to a greater extent.

However, where is the logic in building a temporary venue if permanent infrastructure must be provided to support it? If the temporary venue is removed after the event and replaced with a permanent one, then this might be justified, but this requires further consideration around the legacy of that venue. If there is no legacy for expensive infrastructure, then does this equate to a temporary solution with temporary infrastructure?

The sheer cost, technical requirements and regulations for temporary solutions could vastly outweigh the benefits. In theory, a temporary railway line could be laid, but the material, labour, time constraints, technical constraints and regulations would be no different from a permanent solution - hence no real benefit plus the additional cost of removal.

This brings the issue back to planning and being able to provide for the games and the future use with a single solution. Host cities must be responsible for this to ensure that unnecessary infrastructure is not constructed to destinations that will only exist for two or three weeks and conversely, that no venues are constructed without the means to access and operate them in the future.

Proximity, safety, travel times and distances are important issues for the games. Organising bodies place significant emphasis on the proximity between villages and event venues as well as villages and practice venues. Some athletes may travel to and from practice venues more than five to 10 times, yet will only compete once. Proximity to the main city is important too, not only for athletes who may want relaxation time, but for also the legacy use of the village.

Certain events will be more popular than others, which will influence transport patterns, location, spectator capacity and, ultimately, the permanent or temporary nature of a venue. Delivery agents and host cities must ensure that the relationships between the games village and the key venues are in accordance with spectators and the organising bodies’ expectations, both for the games and the legacy use.

Environmental protection and sustainability

Cities face the dual challenge of managing the major investment and infrastructure development necessary for an event to be a success, while making sure that it is undertaken in a sustainable manner.

Cities desire hosting major events because they can be a catalyst for major redevelopment and improvement. To do this responsibly requires the implementation of an environmental programme that addresses the requirements of host cities, while meeting the expectations of organisations like the United Nations Environmental Programme, in the case of Olympics and affiliated events. Host cities must also consider their obligations for reducing greenhouse gas emissions (including CO2), renewal energy targets and the energy-in-use demands of the facilities.

It should be noted that while most major events are short, from two to six weeks, the main impact is primarily seen in the three to five-year period beforehand (during construction and development) as well as the 10 to 15-year legacy period afterwards. Temporary alternatives still have to be manufactured somewhere, and therefore contain embodied energy and carbon, but at least their impact can be controlled and minimised to a greater extent.

A healthy, pollution-free environment is of paramount importance for athletes and the creation of such an environment benefits the wider community. Sustainability targets will mean

the benefits continue after the games.

Additional considerations relate to the meteorology of the host city. In many instances it is necessary to implement venue environmental control systems. This might mean that venues need to be heated (such as in the Winter Olympics) or cooled (such as in Athens 2004). Modern venues must also incorporate the most energy-efficient options and renewable energy solutions to ensure that a host city’s carbon footprint is kept to a minimum, greenhouse gas emissions are reduced and pollution targets are sustained.

One could also consider omitting roofs or facades. However, the benefits must last during and beyond the games and support the long-term legacy use of the buildings. If there is no planned legacy use, or a building cannot be run efficiently, serious consideration should be given to whether or not that venue becomes temporary and dismantled post-games.

It is essential that political support and stakeholder buy-in are accomplished through every stage, from design through procurement and implementation. Without this, venues cannot be adequately incorporated into the long-term planning of communities and neighbourhoods.

Accomodation demands from stakeholders

Organising bodies like the IOC, Commonwealth Games Federation and other international federations, alongside the press operations, all contribute to the design and functionality of a venue. Thus, the complexity of the venue does not diminish by virtue of its temporary status and the functional requirements are as onerous as for a permanent equivalent version. Hence, the demands on servicing, accommodation needs, space requirements, seating, lighting, field of play and security are still significant cost drivers. However, the key issue is to understand what portion of that venue would be necessary after the event to enable its legacy use and what portion is necessary to host the event, which could be provided as overlay in part.

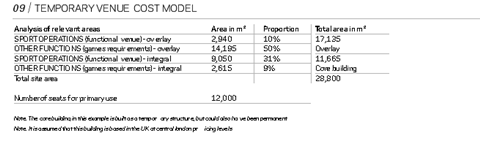

Chart 1 represents a typical multi-use venue with a 12,000 seat capacity (about 29,000m2 GFA including the seating area of 5,000-6,000m2), and illustrates the proportion of functional venue space (termed “sports operations”) versus other functions (the collective games requirements). Forty-one per cent is allocated as sports operations, split as follows: 31% is integral to the building itself and incorporates the event field of play, athletes’ changing facilities, competition management, equipment storage, athletes’ amenities and the seating bowl. The other 10% is provided as “overlay” and incorporates warm-up field of play.

Capital expenditure finance options

Finance is obviously a major issue for cities to consider when bidding to host a major event. Although venues typically account for a relatively small portion of the overall budget, the actual quantum is still significant. Right are the relative proportions of spend on the London 2012 and Rio de Janeiro 2016 Olympics.

Numerous financing arrangements and options do exist, but leading on from earlier questions - if there is no business case for a venue and minimal return from ticket revenue, venues become extremely difficult to finance. It is not surprising that organising bodies like the IOC require applicant cities to provide national government guarantees to finance any shortfall. With such pressure on host cities, surely temporary solutions would be the key favourite? Or is the cost of a temporary venue so high, that it makes no difference?

Until now we have considered some of the high-level issues facing host cities such as size and scale, games versus legacy demands, technical factors, infrastructure and transport issues, environmental issues and stakeholder accommodation requirements towards the detailed micro end. Finally, we will consider the holistic cost of a temporary venue.

The following cost model highlights the hidden complexity and the underlying cost drivers - thus taking cognisance of the infrastructure as well as the operational aspects, the planning, design, construction, acquisition, operations, maintenance, renewal and rehabilitation, depreciation and replacement or disposal. Below are some of the key characteristics of a world-class temporary venue that will influence the cost and design:

- Versatility: it must be capable of hosting multiple events

- Adaptability of the structure: it must be capable of changing its functionality in under 24 hours and in extreme cases, less than 12 hours

- Adaptability of the field of play: it must be capable of converting the playing area to cater for sports with different dimensions

- Capacity: the venue should be able to house a minimum of 10,000 spectators to ensure alignment with typical ticket sales forecasts and demand for particular sports or disciplines

- Material selection: two-thirds of the materials used in the construction are recyclable or reusable. Whatever is not absorbed back into the local market must be capable of being recycled.

Downloads

Temporary venue cost model

PDF, Size 0 kb

No comments yet