When family-run businesses are handed down from one generation to another, all manner of issues come into play, not least of which is ownership. Roxane McMeeken looks at how to keep a construction dynasty going

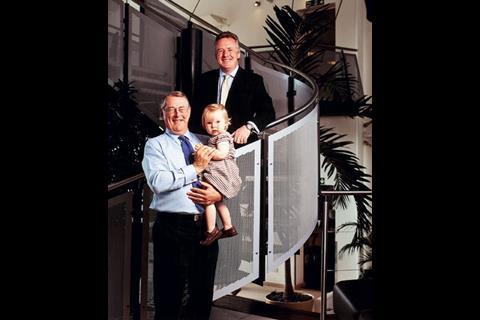

It took a long time for Paul and Philip Hodgkinson to buy back all the shares of Simons Group, their family business, from extended family members and former executives. Paul, the contractor’s chairman and chief executive, says: “At one point, there were 40 shareholders. My brother and I have spent the past two decades buying them back.”

Keeping control of the business is a struggle that many family-owned companies face. Family firms are affected by a range of unique issues, including losing control of shares as a result of divorce settlements, the decision to appoint family members to run the business and transferring the company between generations. Although all firms face financial and strategic issues, when a business is family-run, emotional histories become an added complication – witness last year’s public feud in the Miller family over selling a large chunk of that business. With construction being such a bastion of clans – think McAlpine, Miller and Wates – the potent mix of love, money and power affects many in the industry.

So how do you keep a construction dynasty going? Building spoke with the heads of some of construction’s biggest family firms to find out what problems they’ve had and how they overcame them.

Keeping a business solely in the family is something few of them achieve, according to BERR, the Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform. It recently found that 77% of small and medium-size family businesses are controlled by the first generation, 10% by the second generation and 6% by the third. As the business is passed down it becomes increasingly likely that it will be sold or closed.

Andrew Osborne, group corporate development director at Osborne, is part of the second generation running his concern. He says passing the business down to the second generation was relatively easy, but it gets more complicated after that. So it’s vital to prepare well in advance for the transfer to the third.

Osborne says: “My dad, Geoffrey Osborne, started the business in 1966. He died three years ago and left four children imbued with his values. But it’s when the third generation comes into play that it gets difficult. That’s when you get battles between cousins competing for control of the business, or trying to sell their share to outsiders. If you don’t get the right legal structures in place to guard against this, you will have major issues.”

So what is the current ownership structure of Osborne? The firm is 90% family-owned, with the shares split between Andrew, his brother and sister and their mother. “I hold a slightly larger stake because I’m the one working in the business,” he says.

The remaining 10% is owned by current and former directors. Osborne says the family is prepared to sacrifice some shares to non-family members because that gives them an incentive and reward. The total stake outsiders can hold is capped at about 10%, however. “We don’t want to have a load of mini shareholders,” says Osborne. “The more shareholders you have, especially if they are distant from the business, the harder it is to balance all their demands and avoid difficulties.”

Also, distant shareholders who are not working in the company tend to focus only on dividends, whereas those involved in running it focus more on long-term investment.

But how will the Osborne family handle a transfer of the business to the third generation? Andrew is only 41, so any transfer is likely to be some way off, but the family recently agreed a handover structure. He says this is both in case “I get run over by a bus” and because getting the whole family to agree on how it will work well ahead of time should stop a feud erupting further down the line.

Osborne declines to reveal the handover plan in detail but says that a family forum was set up in autumn 2007 to agree a plan. The family was helped by the Institute for Family Business, which advises and promotes family firms, and has many members in the construction industry, as well as the usual lawyers and accountants.

The Osborne handover plan is not yet concrete, since the five members of the third generation – all of whom are under 25 – have yet to decide if they will get involved in the business. But the plan makes clear how shares will be passed down and how family members who want to get out can dispose of their holdings – presumably without selling them to non-family members. The point, says Osborne, is to plan as far in advance as possible.

If a divorcing couple are forced to split their assets, it can cost a huge pile of money for the family to buy back shares from the ex in-law.

Huw Davies, The IFB

There is no stock market to value the shares of a family business, so working out what they are worth is difficult. Paul Hodgkinson says the problem is more acute when someone holds shares but doesn’t work in the business; for example, when a former director’s spouse holds shares. “Because they’re less familiar with the day-to-day realities of the company, they tend to have an inflated idea of what their shares are worth,” says Hodgkinson.

Osborne’s solution has been to develop a rough formula for valuing shares – again, it is about planning in advance and not leaving things to chance. “Our formula is based on the share prices and dividend yield of other construction firms, plus our net assets, but it’s not entirely scientific. I do it myself – I am an accountant after all – and present the figure to the individual receiving the shares. If they didn’t feel it was fair, then we would get an outside party to agree a reasonable price. So far this has happened only once.”

But what if rebel family shareholders threaten to sell shares to non-family members? This can wreak havoc on the family members who are still working in the business. We saw this recently at Miller Group. The family, which is 110th on The Sunday Times Rich List at £730m, had a public row towards the end of last year. Keith Miller, chief executive of the group, faced a group of family shareholders wanting to cash in their shares. His cousin James, the firm’s former chairman led a group that wanted to sell their holdings, totalling 60% of the company, to non-family members.

The spat was resolved in April when Miller sold a stake to the Bank of Scotland. Keith Miller says he went through a tough time and describes the family rebels as “toxic”. But he says he is happy with how things have turned out. He won’t reveal the size of the stake taken by the bank, but now all the remaining shares are held by just four family members – Keith, his sister and two cousins.

The issue of involving non-family members also needs to be thought through. Andrew Wates, who has just retired as chairman of his 111-year-old family business, says the secret is to bring in outsiders if they are the best person for the job. The Wates family decided this in 2000.

Andrew says the family came to the brave admission that they were not the best people to be at the helm when the firm went through a tough patch. “We had delivery problems at the time,” he says. They brought in Struan Robertson, a BP man as chief executive, and the company’s fortunes improved. The firm has continued to thrive under Paul Dreschler, and Andrew says today, the Wates family focus on being owners, not executives. “In this business, people get to where they are based on merit.”

Other family businesses will go to extreme lengths to stop outsiders getting involved in the firm. For example, it is rumoured that the McAlpine family has put a clause into its family constitution stating women are not allowed to hold shares in the company. Sir Robert McAlpine declined to comment, but the family appears to have seen a few divorces, which could have inspired the alleged clause. For example, Alistair McAlpine, a former director of Sir Robert McAlpine, is on his third marriage.

Huw Davies, development director at the Institute for Family Business, says: “Families are increasingly keeping shares within the family, but this is easier said than done.” First, prenuptial agreements are not legally binding. Second, if a divorcing couple are forced to split their assets, it can cost a huge pile of money for the family to buy back shares from the ex in-law.

So is there a solution? “Basically, no,” says Davies. The best you can do is ensure your family constitution doesn’t allow shares to go out of the bloodline, although even that can be legally challenged.” Careful planning can help avert the worst-case scenario. Andrew Wates believes that setting out plans in the form of a family constitution (see box left) is the best way to keep the business on track. He advises drawing one up as early as possible, ensuring all the family agree on its terms, but warns that it must be reassessed.

Wates drew up its charter in 1994, reassessed it in 2001 and, earlier this year, when it handed over to the fourth generation, another agreement had to be thrashed out. These processes can be painful, says Wates, but in the long term they could save your business.

The recent handover from third to fourth generation was a tense time. Tim Wates took over as chairman from Andrew, who has retired but remains on the board. It also involved ownership of the company being spread more widely, from three family members in the third generation (Andrew, Paul and Michael) to a further five (Tim, James, Johnny, Andy and Charlie) in the fourth. “It took six months to hammer out our recent handover process and there was really heated debate. It involved eight intensive away days where we discussed nothing else. But we all had to compromise and now we have a structure we all agree with.” But even after a successful handover, Wates says family businesses can remain tempestuous and he recommends “eternal vigilance”.

The Durtnell story

Founded in 1591, R Durtnell & Sons is on its 13th generation and is based at the Kent site where it was founded. The firm’s first-ever project, an oak-based house called Poundsbridge Manor near Penshurst in Kent, is still standing today. The firm has a turnover of £70m, employs 170 staff and is 100% family owned. The Durtnells appear to have mastered the art of keeping a family business going. How have they done it, and can they maintain it?

The secret to the amazing longevity of the business is simple – ownership has always passed from father to son, eliminating the problems of a widening base of shareholders.

However, Geoffrey Durtnell, the father of current chairman John, changed this tradition when he handed the company over to his three children. As a result, today there are three main shareholders: chairman John, his sister and his brother’s family. There are also six minor shareholders, who belong to the younger, 13th generation. All are family members and they have a growing brood of children.

Director Alexander Durtnell, son of John, admits that the family business has new complications. “Now we’ve got something to think about. In theory there will be six shareholders when we hand over to the 13th generation, but there could be more, and after that, who knows?”

The Durtnells drew up a family charter two years ago, which aims to smooth out the potential problems they face. “It’s not legally binding but it sets out the family’s views on how we want to run the company and what we expect in future – and we’ve all signed up to it.”

The charter says if someone wants to sell their shares they will be expected to sell to a family member. The value of the shares would be worked out by an independent expert.

Alexander Durtnell says: “We’ve not had anyone wanting to sell their shares yet, and I would say it’s unlikely. We’re a pretty happy family.”

A family charter should set out:

- Share ownership, valuation and transfer, and how dividend payments work

- Succession planning

- The obligations and rights of family members involved in the business

- Management structure

- Business strategy, objectives and values

- How disputes will be resolved

Institute for Family Business is a not-for-profit membership association that supports UK family-owned businesses through advocacy, education and research. Visit www.ifb.org.uk for more information.

Loosening the ties that bind

Although many family firms struggle to maintain control of the business, others are willing to let go entirely. This is what happened at Mansell, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. The contractor was owned by three families – Adams, Hill and Mansell – in 2003, when Balfour Beatty bought it for £43m. So how did they achieve such a dignified exit?

The firm was founded by Robert Mansell, who passed it down to his son Robert Freeman Mansell. Leon Hill, now 88, spent his entire career in the firm, which he joined in 1937 as a trainee surveyor. He and his colleague, Bernard Adams, worked their way up, each buying a growing number of shares, until the two of them owned shares which together were almost as much as that of Robert Freeman Mansell.

When both Adams and Hill, who had ended up as chairman, retired in the early nineties, the only person from any of the three families working in the business was Hill’s son, Christopher. Leon Hill says: “Nobody within the three families wanted to take the business on. My son had trained as a lawyer and that’s what he wanted to do, really.”

It was clear the business had to be sold, but how? “We had to think carefully about inheritance tax. We were not a public company so we couldn’t sell our shares on the open market,” says Hill.

The families thought about listing on the stock market, but the firm was not big enough (Mansell’s turnover was then £500m) to list on the main London exchange. The other option was to list on the Alternative Investment Market, but Hill was advised at the time that investors in that market preferred

fast-growing stocks, whereas Mansell’s performance was strong and steady.

Finally the families decided their best bet was to split the shares between their children and sell the firm wholesale. Leon Hill made about £4.5m out of the sale to Balfour Beatty. He says: “There weren’t all that many construction companies big enough to buy us, so we were lucky Balfour came along.”

Does he regret that the business is no longer in the family’s hands? “The family of the participants in a business are not necessarily going to be interested in running the company. They might not have the talent for it. It would be nice if all the family became accountants, but you have to accept it’s not always going to be the case. I still watch Mansell closely. It’s nearly on £1bn turnover now, which is very pleasurable to see.”

The shareholding structure at Mansell illustrates a different approach to family business than that of firms such as Simons Group. While Paul and Phillip Hodgkinson have painstakingly been concentrating shares in their own hands, the Mansell family encouraged two other people (Leon Hill and Bernard Adams) to build up shareholdings. “I suppose it was an unusual strategy,” says Hill. “But the Mansells only had one family member working in the business and they wanted to ensure our continued participation in the company. And for a long time it worked; it stopped us going elsewhere.”

Postscript

Original print headline 'Keeping it in the family'

No comments yet