A growing urban population with complex buying behaviours will require a dynamic and agile logistics network from UK retailers keen to make the most of this fast-moving market

01 / The retail distribution centre market

The UK’s retail sector continues to grow. The Office for National Statistics predicts that retail sales will increase by 1.9% this year and 1.7% in 2017. Much of that increase comes from online sales, and this trend is set to continue, with some analysts predicting online will account for 21.5% of the UK’s total retail sales by 2018 – the highest online retail share in the world.

Despite this, consumer spending patterns will be unpredictable, fluctuating from month to month as buyers respond to short-term offers and price cuts. High-profile promotions like Black Friday will continue to have a big impact as buyers hold off spending until those sales open.

Online sales, while growing, will be competitive and so retailers will need to differentiate themselves with USPs such as same-day delivery and free returns.

The challenge for retailers will be how best to establish a cost-effective logistics network that is agile enough to meet the needs of an ever-demanding client base.

This, in turn, will have an impact on the size, specification and number of distribution centres that they require.

02 / Distribution centres: What and where?

Efficient logistics depends on two key factors: warehouse spaces and the infrastructure connecting them.

In 2015, the demand for high-quality warehousing was outstripping the supply. By the end of the year, the market had reacted, with speculative facilities springing up around the country – a trend that has continued into 2016.

Retailers are also moving away from building massive regional distribution centres, instead favouring smaller facilities of between 5,000m2 and 25,000m2, close to population hotspots. It is in this market that we are seeing a growth in speculative developments.

This may be a sensible strategy. The UK’s population is forecast to rise from 65 million in mid-2014 to 75 million by 2039, with most of that growth in cities. The demand for distribution centres around these major conurbations will be intense.

The omni-channel challenge

Logistics networks to feed the new distribution centres will need to be flexible and dynamic. Retail habits change quickly. ”Omni-channel” shopping – where customers visit stores to investigate products, and then go online to make their purchase, often benefiting from cheaper deals and fast delivery – is on the rise.

Distribution centres will have to serve stores but also accommodate customer deliveries, requiring adjustments to layout and new docking arrangements to suit a different fleet.

Retailers looking to gain a competitive edge are also making it easier for consumers to return products. This in itself is a logistics issue, but, if managed correctly, offers the chance to create a second-tier consumer market system.

Returned products may not be able to go straight back on the shelves, but the volumes involved mean they still have significant value.

Managing returns, sorting and onward sales present a huge opportunity for retailers.

More trains, fewer lorries

What about infrastructure, that second critical factor? In order to support a lean and flexible logistics network, the UK government needs to ensure that the country’s road and rail networks can sustain the physical movement of goods in the UK. Pressure on the roads has to be alleviated by an improvement in the rail network.

This, in turn, will drive the location of distribution centre hubs in prime strategic locations. It’s a nice idea – but, even with Network Rail’s £9bn worth of enhancement to the rail network planned between now and 2018/19, it still feels a long way off.

The client’s view

Steve Cole, development programme manager at John Lewis and Waitrose, offers a client’s view of the retail and logistics market.

The move from traditional, store-based methods of selling to true omni-channel retailing is fundamentally changing the needs of our distribution estate, both for our department store and food store businesses. Large deliveries into shops are now supplemented by far more frequent deliveries to customer homes. Online ordering leads to an increased volume of returned stock, which needs to be quickly turned around again for re-sale. New products and innovative selling channels continue to launch, with accompanying demands on the estate and infrastructure.

To support this in an efficient and productive way while maintaining customer service requires a different shape to our estate and transport network.

Larger central distribution facilities are now being supplemented by smaller regional hubs, offering faster and more agile service to customers and reducing transport mileage. This space needs to be designed to be as agile as possible to allow it to adapt quickly to market, product and packaging changes.

The additional operational cost of customer delivery requires us to develop our estate as cost effectively as possible, but also to the highest quality to ensure minimal ongoing maintenance cost.

So, innovation in design, construction or delivery processes continues to be essential in order to minimise energy demand and design with end-user productivity in mind, not only to meet the John Lewis Partnership’s responsible development vision, but again to keep running costs down.

03 / Design

Simon Rispin from SMR Architects questions whether speculative distribution centre developments are of value to retailers looking to expand their distribution centre estate. SMR Architects is a Yorkshire-based architectural practice working with national clients on logistics and supply chain facilities for developers and operators.

The fact that developers are confident enough to build space speculatively is good news. Confidence in the market is great, and agents are always keen to tell us there isn’t enough space available given known occupier demands.

But with operations becoming more specialist and requirements therefore more bespoke, how do we design to meet such a potential wide range of needs? What are the implications for institutional standards?

A false economy?

Take a typical retail spoke facility: goods come in from a national hub and deliveries go out direct to customers. With a number of these facilities across the country, retailers really only require limited space, as the operation is largely transient. In this situation, typically a dock per 10,000ft2 is loosely institutional – but for a retailer with a large fleet of smaller delivery vehicles, this will be inadequate.

The occupier has limited options: incur considerable costs adapting an existing speculative build to suit their requirements, or roll out a new build to their bespoke requirements.

Getting the design brief right can also be difficult. Floor-based operations don’t need the eaves height developers want and funders expect. Dock heights vary across smaller-vehicle fleets, so assuming a height for the yard becomes tricky. Employee numbers are lower in automated facilities, so office space can be reduced.

Thus the speculative build sits empty. Facilities like this then become of interest only to smaller companies, with fewer exacting requirements and a more flexible operating model. But developers will, no doubt, argue the rents are not comparable.

Flexibility designed in

As architects working for both developers and operators, we see both sides. The key is to provide as much flexibility as you can.

Speculative warehouse spaces could simply exclude any ancillary space, but have modular units planned in.

These would be tailored to the operator, and installed as part of the fit-out – but changeable if the operator changes or requirements grow. A structural frame and grid that allows external dock pods to be installed, and yards flexible enough to meet a growing range of fleet vehicles, are other possible innovations.

People brave enough to build speculatively also need to be flexible enough to get the very best possible tenants. They need to offer something different too. BREEAM and sustainable measures are now commonplace, and should be standard. Operators are looking more and more at the whole building lifecycle, both in costs and in ease of operation. So offer a building model with full FM capability, recording maintenance regimes, with product data for ease of replacement and such like.

At the moment, none of this features in discussion around institutional standards. Perhaps it’s time those standards changed.

04 / Cost influences

Distribution centres are, for the most part, simple, functional buildings. Major cost drivers will tend to relate to the size and arrangement of the building.

Substructure and superstructure

Wall-to-floor ratios will be driven by the building’s layout on plan. In particular, eaves height must be able to cope with requirements such as high bay storage and automation.

For steel-framed buildings, costs will be around the column centres and overall height. Requirements for mezzanine floors and service loadings will also have an impact.

Ideally, floor slabs should be designed around the operational requirements, otherwise they risk imposing restrictions on the distribution centre’s operation.

Floor slab specification should include requirements for:

- Floor loading, ranging from 25 to 50 kN/m2 UDL, as well as point load requirements for rack legs

- Level, vertical tolerances and applied finishes

- Speed of construction

- Layout of movement joints, corresponding to racking layouts.

If amenity blocks are required at both ends of a warehouse, considerable runs of drainage will need to be factored in.

In general, modern methods of construction such as the use of prefabricated or modular components will minimise construction time, and may be more cost effective.

Contractors should look to minimise disposal of materials off site. Waste can be used in landscaping and infill, instead of importing materials to do this, emphasising natural contours wherever possible.

Finally, abnormal site factors, such as existing ground conditions, site drainage requirements or Section 278 work, all need consideration as they could have significant impacts on the costs of development. Investigations up-front may add some time to the programme but will save expensive remedial works later on.

Office space and fit-out

Distribution centres generally require office space, although the office-to-warehouse ratio needs careful consideration. Typically, the office gross internal area equates to 5% of warehouse gross internal area. The cost of building office space is disproportionate to that of the warehouse, so if the ratio goes up, it will increase the overall building cost per m2 significantly.

The institutional standard is to deliver office space to an agreed Cat A specification, which includes the basic MEP and fire services, raised floors, suspended ceilings, with the operator then completing the Cat B office fit-out.

A clear interface between the Cat A fit-out and the operator fit-out is essential to avoid abortive costs and the potential stripping out of newly installed finishes. Ideally, those interfaces would be discussed when deciding on the facility’s procurement method.

Yards, warehouses and docks

Yard-to-warehouse ratios will depend on whether the distribution centre is single- or double-sided, and whether the facility requires a yard all around the building, such as in a through-flow and cross-dock solution. The depth of the yard also needs consideration – this will be dependent on the fleet and the parking facilities required.

Specifications for docks depend, again, on fleet requirements and whether the manufacturer is linked to an approved supply chain/maintenance agreement on other facilities. A general guide for an institutional facility is one dock for every 1,000m2 of warehouse.

Fire protection

The BS EN 12845 (2015) TB 234 standard introduced limitations and protection requirements for different storage configurations, including options to deal with excessive ceiling clearance of more than 4m. This should be considered at the design stage, with special focus on the category of product stored, the zones where products are stored or are transient, and the height of storage.

Retailers should also seek to minimise end-user insurance premiums. This, potentially, affects the selection of the cladding materials and the capacity of the basic sprinkler infrastructure.

Fit-out works will then take into consideration the sprinkler systems, fire compartmentation and the provision of duplicate systems, which are all needed to provide vital disaster recovery capability for the distribution centre.

05 / Procurement and construction

There tend to be two main routes for procuring a distribution facility.

In the developer-led route, the developer constructs the shell based on an institutional standard and then either enters into a lease agreement with a tenant or sells the facility.

The tenant identifies enhancements to the shell which are practical to procure with the shell build, rather than retrofit. These are either factored into the lease agreement or covered by a capital contribution. The tenant then procures a main contractor to complete the fit-out, once they have taken possession of the building. The advantages of this route are, first, that the building fabric is delivered by developers who are experts in building these facilities; and second, capital contributions may be reduced, depending on the lease and financial arrangements of the deal.

In the self-build route, the tenant procures a main contractor to complete the shell and fit-out, which is funded by a capital contribution.

The advantage of this procurement route is that the build can be tailored exactly to the tenant’s requirements. However, if funding is sought from third parties, they are likely to want to protect their investment by insisting on institutional standards such as consistent eaves heights, and so on.

Economies in programme and cost can also be achieved by combining the shell and fit-out works into a single contract.

One or two stages?

In both of these options, the favoured contractual route is single-stage design and build, due to the simple nature of the construction works. However, in other sectors, the market is shifting towards two-stage tendering. Whether those major contractors who specialise in warehouse facilities will seek to re-address the risk profile by moving towards two-stage tendering remains to be seen.

06 / Fiscal incentives

The relatively highly serviced nature of distribution centres, when compared to more basic industrial properties, can generate significant and accelerated levels of tax reliefs on costs incurred.

This is likely to be primarily via plant and machinery allowances which, based on our cost model, could generate relief equating to a cash value of between £1.25m and £2m. The allowances are claimed at rates of 8% and 18% on a reducing-balance basis and will be relative to the expenditure incurred on services installations, furniture, fittings and trade-related equipment such as dock-levellers and traffic controls.

Furthermore, any expenditure incurred on qualifying energy and/or water-efficient technologies could accelerate the relief to 100% in the year of expenditure, or a 19% payable credit for loss-making UK companies.

End-user fit-outs are likely to attract considerably higher levels of allowances, with between 60% and 75% of the cost incurred potentially attracting relief, as this would focus on the occupier’s bespoke services installations, fixtures and trade-related equipment. Contributions made to an occupier’s costs can therefore yield relief to the contributor.

Depending on the particular aspects of a development, Research and Development relief may be available if an innovative construction approach is utilized (including addressing particular site challenges, improved material technologies and construction processes). The rates of relief are generous, particularly for SMEs which can claim a 230% super-deduction of qualifying costs (or a 14.5% payable credit for loss-making firms). Large companies can currently deduct 130% of qualifying expenditure, but from 1 April 2016 this will be fully replaced with the Research and Development expenditure credit (RDEC), providing an 11% “above the line” credit.

Capital projects can also benefit from 100% capital allowances for Research and Development Allowances (RDA) where it is trade related. This potentially enables a full recovery of the construction costs for taxation purposes.

Finally, on brownfield sites, UK companies carrying out site remediation works may be able to benefit from Land Remediation Relief (LRR). This provides a 150% super-deduction against corporation tax, where the taxpayer is not the polluter. Again, for loss-making UK companies, this can be surrendered for a 16% payable credit.

07 / Sustainability

While much of the construction sector has looked to integrate sustainability issues such as energy efficiency into the design and delivery of buildings, the distribution centres market has not seen the same level of take up. Cost and speed tends to trump green buildings.

Nevertheless, the larger corporate retailers have company-wide sustainability policies in place, as part of their corporate social responsibility, which are starting to influence the logistics and distribution centre network.

Tenants/clients are starting to realise that energy-efficient measures not only deliver long-term benefits in terms of running costs, but also improve the value of the asset in general.

In terms of actual “green design” features, institutional standards surrounding airtightness and levels of insulation are being challenged and developers are incorporating these requirements within their shell builds.

Tenants/clients are also looking to reduce the carbon footprint of their distribution centres, specifying features such as triple-skinned, factory-assembled roof lights, optimised natural light to the warehouse, rainwater harvesting for reuse in non-potable applications, low-flush appliances, and energy-efficient office lighting (LED).

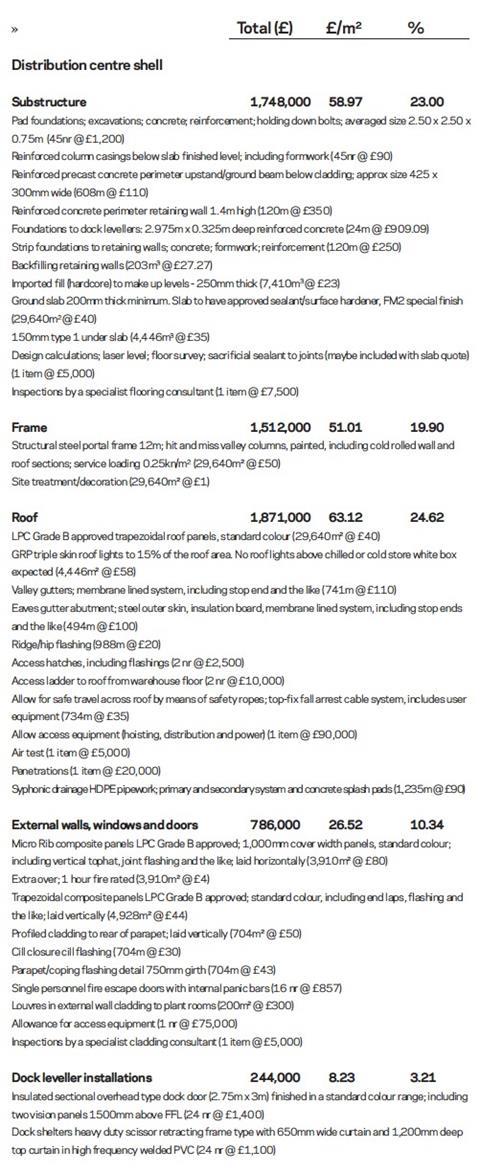

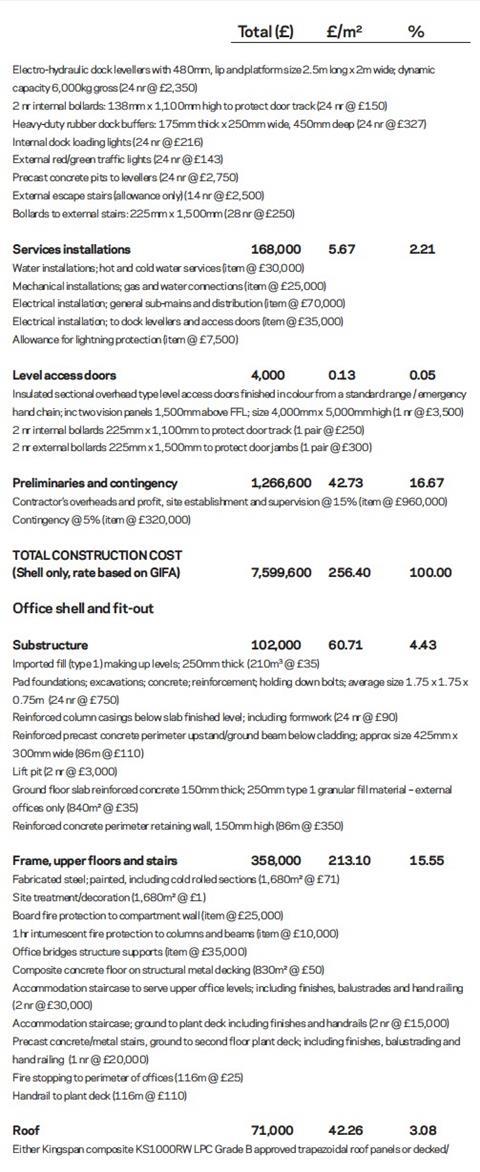

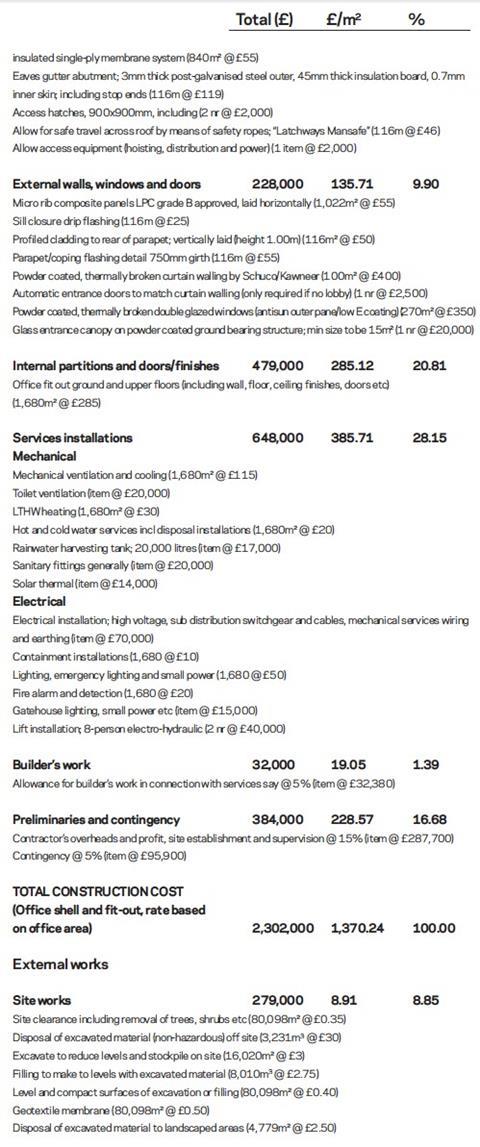

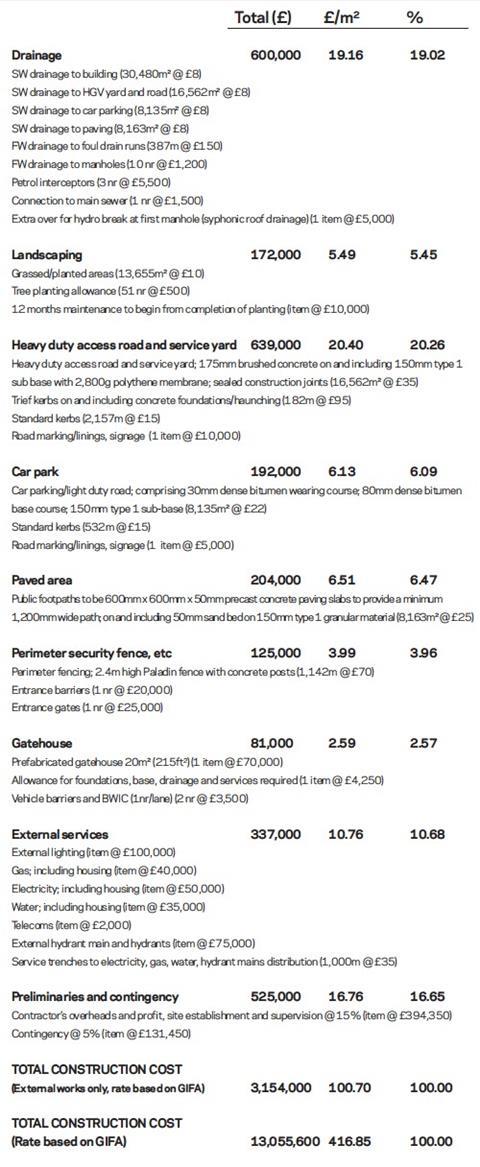

08 / The Cost Model

Aecom’s cost model is based on a single-storey, rectangular-shaped warehouse new building (12m height to haunch) with a two-storey office, with gross internal floor areas of 29,640m2 and 1,680m2 respectively. The development is on a brownfield site, which has previously been cleared. Any land remediation has been undertaken as part of a separate contract. The building has a reinforced in-situ concrete ground-bearing slab, a steel portal frame with reinforced concrete pads, and an aluminium built-up cladding system to roof and walls. External works consist of access and circulation road, car parking, service yard, pedestrian areas, landscaping areas and gatehouse. Unit rates are derived from competitive design and build tenders and are current at first quarter 2016, based on a West Midlands location. The building-only (shell and core) cost of £417/m2 compares with lower-quartile costs collected by the BCIS of between £329 and £799/m2 for new-build industrial units with a GIFA of 10,000–30,000m2 in the West Midlands.

The costs exclude the warehouse fit-out, the Cat B office fit-out, non-fixed fittings, tenants’ specified work, enabling works and demolitions. The costs of professional fees and VAT are omitted. Unit rates should also be adjusted for location, site conditions, programme and procurement route.

No comments yet