Josephine Smit looks at progress on the upgrading of Britain’s existing housing stock

Homeowners have got off lightly, for now. The government has postponed proposals in the revised Part L of the Building Regulations to require existing homes to be made more energy efficient when they are refurbished, extended or converted. Such a move would be a step too far in the present political climate.

The need to upgrade the housing stock remains pressing, though, and no one knows more about the challenges ahead than the registered social landlords (RSLs), owners of much of the UK’s 7 million social housing units. The affordable housing sector is still working on an earlier government-initiated programme called Decent Homes. It involved relatively simple measures to bring homes up to a standard of comfort and modernity, comfort being provided by central heating and double glazing and modernity by new kitchens and bathrooms. But the upgrading of the 3 million homes deemed to be “non-decent” is still not completed nearly a decade on.

Now consider the prospect of making good the government’s pledge that carbon emissions from existing homes be cut by 80% by 2050. Or meeting the Greater London Authority’s requirement that housing stock in its boroughs should meet a 60% carbon reduction target by 2025.

The Peabody Trust, a London housing association, asked De Montfort University in Leicester to put a price on meeting the 2025 target for its stock of 18,000 homes. The answer was £100m-£150m. The cost of upgrading all existing housing, both private and affordable, for the 2050 target could be as much as £500bn, a Housing Forum working group reported earlier this year. How such a sum can begin to be raised in a recession is the subject of much debate.

“Decent Homes has paved the way in making large-scale improvements to properties, but the carbon target is potentially much bigger in scale and cost,” says Nicholas Doyle, project director at one of Britain’s largest housing associations, Places for People. It is a founder member of the Existing Homes Alliance, which campaigns for low-carbon refurbishment of the housing stock, and is also comparing experiences with other “retrofit pioneers” in the sector. Projects completed so far have shown that the average cost of a green retrofit for a house is £20,000-£25,000.

Doyle says: “About 20% of our stock, or 8000-10,000 homes, are ‘hard to treat’ and would require fairly extensive upgrading, but we could do a lot more to a lot more properties. The SAP rating on our stock is fairly high, but we still have substantial numbers of homes to upgrade.”

Common approach

Environmental upgrading solutions may vary according to homes’ construction methods and location, but Doyle says there can still be a common approach: “First, you can improve the thermal performance. Second, you can improve the way you manage energy, that is the heating and hot water. Third, you can look at where you get your energy. Each of those areas costs about £8000-£10,000 to bring you to the 80%.”

Alistair Sivill, technical director with social housing contractor United House, says it is a matter of getting the value right. “If you go to a higher energy saving level, the cost goes up tremendously. You can give three homes a 50% carbon saving for the cost of producing a 70% saving from a single home.”

United House has a methodology for green upgrading that helps to assess value. It is carrying out Decent Homes work on 6000 council homes in Islington, north London, under the country’s largest housing private finance initiative project.

A demonstration project resulted in a 70% carbon saving alongside a Decent Homes refit. United House achieved this by an approach it calls Value Carbon, a matrix that allows it to assess what measures to incorporate and what to leave out for a target carbon saving. The best six improvements it specified for the 600ft2 Victorian ground-floor flat in Aubert Park produced a 50% carbon saving and cost £7000 (see tables in graphic, below).

United House is conducting research aimed at making its green upgrade run as smoothly as the Decent Homes upgrade. Sivill says: “Our intention is to do this work in five days or so, with the tenant in situ.”

Newbuilds are designed for theoretical occupants with perfect green lifestyles, but existing homes have residents who may not behave in line with a computer model. Although United House chose some new technology, it kept the products simple for cost reasons, for practicality as the location rules out many renewable energy options, and for ease of use for residents. “This is about doing what’s cost-effective and doing the basics well, and then pushing the boat out just a little,” Sivill says.

Drum Housing pushed the boat out more than a little when it worked with the consultant ESD (now Camco) to upgrade six homes in Hampshire two years ago. The aim was to halve tenants’ energy bills and cut carbon emissions by 60%, and it trialled a range of technologies including ground source heat pumps, photovoltaics and waste water heat recovery.

Drum found that residents struggled to make the most of some of the technology. Paul Ciniglio, sustainability manager at Radian Group, says: “We had to do an awful lot of work in explaining to residents how to use ground source heat pumps.”

BRE monitoring of the homes has found that the CO2 reductions often exceed expectations but the halving of running costs is not always achieved. “A lot of the benefit appears to have been taken up by residents in thermal comfort,” says Ciniglio.

Tenants may be able to enjoy warmer homes for now, but that comfort could be short-lived if energy bills soar in the future. As Nicholas Doyle says: “We can’t get to the situation where tenants have an affordable rent but can’t afford the heating and hot water for their homes.” Fuel poverty may be a more powerful driver for change than the Building Regulations.

Project 1: Woodfields, Kingsley, Hampshire

(See picture, top)

The project: Drum Housing upgraded three 1950s three-bedroom semi-detached houses and three two-bedroom bungalows with:

- cavity wall insulation

- 300mm loft insulation

- double glazing

- mechanical ventilation with heat recovery

- waste water heat recovery

- ground source heat pumps – 3.5kW for bungalows and 5kW for houses

- solar photovoltaics – 1kWp systems producing 800kWh per array

- low-energy lighting

Average cost of upgrading per unit: £23,000

Target CO2 reduction: 60%

Actual CO2 reduction: 49-83%

Project 2: Aubert Park, Islington, London

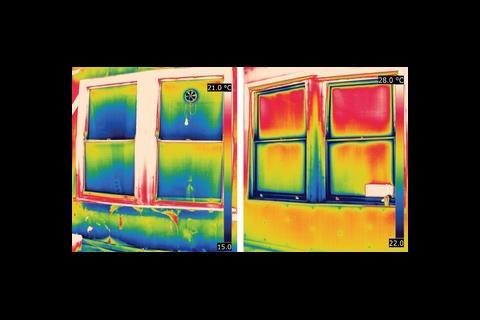

(See pictures, top right)

The project: United House upgraded a one-bedroom ground-floor Victorian terraced conversion flat with:

- Baxi micro combined heat and power unit

- Aerogel insulation to external and party walls

- vacuum glazing in existing sash windows

- Vent-Axia mechanical ventilation with heat recovery

- low-energy lighting

Cost per unit: £22,000 for the 18 measures that produced a 70% CO2 saving. Further measures, including monitoring by BRE, produced no extra carbon saving and raised the cost to £30,000.

CO2 saving: 70%. United House did not have a target figure and instead sought to get the maximum carbon saving for money spent.

Six things you should know About upgrading homes

1 80% is the target CO2 saving set by the government for existing homes by 2050, but not all of that saving will have to come from the actual buildings. Decarbonisation of the electricity supply could mean that the ultimate saving from the home is 60-70%.

2 The target is for “overall” emissions and so includes domestic appliances. Energy use should be reduced inside the home as well as by it.

3 It has been estimated that government needs to inject £2bn a year to kickstart a housing refurbishment programme.

4 Although many projects are already being carried out around the UK, they are relatively small scale and so the sector is not yet exploiting economies of scale and does not yet have the skilled workforce required.

5 Projects carried out to date are showing that simple actions are best. The biggest successes are from insulation, low-energy lighting and light pipes.

6 Residents are finding it difficult to use new technologies to best effect. Project teams are writing simpler user guides. Should manufacturers make their products easier to operate?

Downloads

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet