The revised definition of “zero carbon homes” is eagerly awaited. Neil Jefferson looks at key areas of concern

The consultation period for the Department for Communities and Local Government’s proposals on the definition of zero carbon homes closed on 18 March. The consultation document followed a report from a task group set up by the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), which reviewed the definition of “zero carbon” in the government’s Code for Sustainable Homes. The UKGBC report said the current requirements for “zero carbon” could result in up to 80% of new homes being unable to meet the definition.

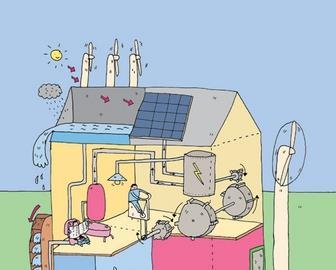

The Department for Communities and Local Government (CLG) consultation has been concerned with what is best described as operational zero carbon – the design and construction of homes that, in the course of their operation, do not add to the carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This includes emissions from space heating, ventilation, hot water and fixed lighting, but also unregulated energy usage (powering of appliances, for example), which is typically about 35% of a home’s total energy use.

CLG Proposal

The consultation proposed a hierarchical framework that first addresses the issue of “energy efficiency”. All new housing will have to be built to very high levels of energy efficiency, achieved by having an appropriate building form, good fabric insulation and good airtightness standards, and the consultation document suggested requirements similar to PassivHaus and Energy Saving Trust advanced practice standards.

Beyond the reductions achieved through energy efficiency improvements, there should be provision of on-site renewable technologies and/or direct connection to a district heating system that produces little or no carbon dioxide. This second level of the hierarchy is called “carbon compliance”, and the consultation invited views on the minimum level that should be achieved on-site, from a 44% cut in CO2 (compared with Part L 2006) to a 100% reduction.

The new concepts in the definition were “allowable solutions” to achieve zero carbon and a potential cost review in 2012 to provide increased certainty.

Put to the vote

The Zero Carbon Hub ran a series of eight interactive workshops at which more than 500 delegates gave their views on key consultation questions.

The opinions expressed at the work- shops showed the complexities faced by those trying to steer the definition. This is clearly a challenging time for the house-building industry and cost and delivery issues dominated the open sessions, along with concerns about how off-site provisions will be set and enforced.

In the electronic voting part of the sessions, a significant majority of the audience indicated that legislation was the right way to make buildings more energy efficient and that any standards should be introduced in two steps.

A significant majority indicated that the estimated additional costs for carbon compliance set out in the consultation were too low, and this response did not change appreciably among those builders that already had experience of construction to higher code levels.

When asked about carbon compliance levels, the workshop audience was split fairly evenly between the proposed 44% and 70% levels, with fewer opting for a 100% reduction. A large number felt that percentage levels for different dwelling types should vary. The majority of delegates voted to adopt the same approach for non-domestic buildings.

CLG is expected to publish its final report this summer. The government would like to see a three-step change to Building Regulations over seven years. This would be an unprecedented pace of change, with housebuilders and their clients having to explore new solutions rapidly without creating risks for new homeowners.

The industry will need to innovate with care, build in rapid feedback mechanisms, constantly reassure buyers and train those designing and constructing new homes to the highest levels.

more flexibility

Many sites may be unable to mitigate all their emissions by carbon compliance, so CLG is proposing a list of allowable solutions. These include:

Fulcrum says this is much more flexible than the Code for Sustainable Homes Level 6, which requires all technologies to be directly connected to the site.

Expert Opinion - Jules Saunderson

The definition of “zero carbon” outlined in the consultation document is a welcome departure from the thinking behind the definitions in the Code for Sustainable Homes or the stamp duty land tax relief scheme.

It is disappointing, however, that the government has failed to take forward the most enticing of the UKGBC’s recommendations – the creation of a Community Energy Fund.

Few can argue with the logic behind the hierarchical approach proposed in the consultation, but it becomes complicated when you get into the details. Setting the level of “carbon compliance” required is a crucial policy lever as current market forces do not incentivise on-site mitigation.

It is impossible to set a single standard for the entire industry as the level of mitigation that can be achieved depends on the specific site and the details of the proposed development.

For this reason the UKGBC task group proposed that the price of paying into the fund could be used as a market mechanism to incentivise developers to use on-site renewables without placing an undue burden on sites that were genuinely constrained.

The list of “allowable solutions” proposed in place of the fund are, according to the associated cost analysis, cheaper on average than on-site measures and therefore developers are likely to opt for these measures as soon as possible in order to save money.

We believe that the fund mechanism gave greater certainty to developers looking to make strategic investment while providing greater flexibility on what the fund could be spent on in order to maximise the kg/CO2 saved per pound of investment.

Expert Opinion - Dave Worthington

The zero carbon definition consultation document goes a long way towards addressing the urgent need for greater certainty on the regulatory requirements for newbuild development post-2016.

It has also prompted a much-needed wider debate about the delivery of green infrastructure and the decarbonisation of existing homes.

Given the pace of change in the development of low- and zero-carbon (LZC) technologies, it is understandable that some level of flexibility is required in moving forward, but CLG is trying to achieve a delicate balancing act and there are complex issues to be unpicked and resolved.

One important factor is that the refresh rate of housing is such that there is a need to “lock in” a level of carbon performance within newbuild developments that reflects the likely carbon emissions trajectory over the next 60 years.

This was reinforced recently in the government’s Heat and Energy Saving Strategy consultation document, which indicated that we need to aim for emissions in existing buildings to be approaching zero by 2050.

This suggests that we need to take fabric improvements beyond the currently accepted “best practice” standards regardless of any contribution from LZC measures, which may fall out of a carbon compliance target.

CLG should be commended for maintaining the fundamental principle of the policy to offset fully the carbon emissions of all new housing, but the challenge now is to narrow the list of “allowable solutions” to those that will provide real additional benefit over and above a long list of other regulatory and policy drivers.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Postscript

Neil Jefferson is chief executive of the Zero Carbon Hub, a public/private partnership co-ordinating the delivery of low- and zero-carbon new homes

No comments yet