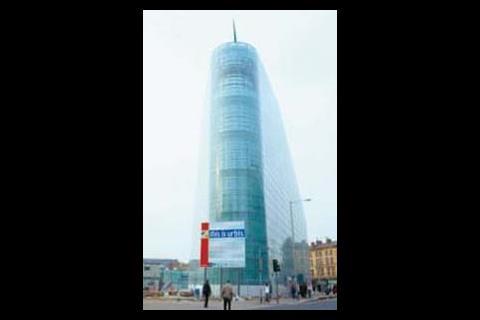

Canary Wharf too has a number of schemes on the drawing board and under construction, including the new headquarters for Barclays Bank. The 33-storey building is the UK's first high-rise to be designed and constructed since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Centre. Known as BP1 it stands out due to the measures taken to protect it against terrorist attacks and other emergencies. Enhancements include incorporating more and wider escape stairs than standard to improve evacuation times and locating half of these in the central core. There are also refuge rooms within the concrete core on each storey capable of housing all the occupants for an individual floor. So can we expect this to become a blueprint for future tall buildings? A lot seems to depend on whether the development is speculative or client driven. Speculative developers rarely want to spend more than the bare minimum, while owner/occupiers might have a specific need for a higher spec building.

Terrorist attacks and natural disasters can never be totally ruled out but office buildings with all their associated life safety systems are still amongst the safest places to be – you are probably 20 times more likely to die in a domestic fire than in an office fire.

The situation in Hong Kong, which has one of the highest concentrations of tall buildings in the world, is different. Here strenuous codes of practice on the means of escape for high-rise towers have been in place since 1996. Designers are obliged to to incorporate refuge floors placed every 15-20 storeys when the building is in excess of 80-storeys. These floors, served by high speed lifts, and are open to the elements to prevent them being put to any other use.

This might be considered forward thinking but there are drawbacks. "It adds significant cost onto a building so it's a case of persuading developers to have a whole floor which does nothing," says Miller Hannah, principal of Hoare Lea Fire Engineering. "It would have to be a legal requirement for them to do it."

Changes in legislation are often instigated by disaster. "You need something that will act as a catalyst to change," says Hannah. But designing a tall building to withstand an attack such as that on the World Trade Centre would be, if not impossible, hugely expensive and require a significantly beefed-up structure.

Simon Russett, lift engineering principal with Hoare Lea raises the point that full evacuation isn't always desirable, if a fire breaks out on the tenth floor of a 50-storey building it doesn't result in the entire building being evacuated. "If it is a bomb scare and you're not sure where it is you don't want to evacuate people in case it is in front of the building." Similarly there is little point evacuating a building during a typhoon if it has been designed to withstand such forces.

You can run down 20 storeys to safety in a few minutes, but 60 storeys, with people-packed stairwells, is a different matter.

In the event of an emergency such as a fire the standard procedure is to evacuate by foot rather than using the passenger lifts. Lift shafts connecting all levels present a major path for fire and smoke, the piston effect generated by the movement of lifts may increase smoke spread and the loss of power to the lifts as well as the potential for lifts to be called to fire floors due to adverse effects on the controls are all dangers. Others however see scope, in Europe and the US, for using conventional passenger lifts to speed up evacuation times, particularly given the trend for increasingly high buildings. Proposals put forward include having drivers for each lift car who could take control of the public lifts during an emergency to direct the evacuation procedure. Lifts could then be used as shuttles ferrying passengers from the refuge spaces to ground level, targeting the most vulnerable floors first. Additional safety features would include designing the lifts to be fire and smoke proof and having back-up power supplies along the lines of BS5588 Part 8 for escape lifts.

Psychological aspects also come into play. "Most people want to go down when there is a fire alarm," says Rusett. "People are not that likely to run up, even if there is an evacuation floor three storeys above." In practice this means that most occupants will naturally start heading for the escape stairs. "If you are at the top of a 20-storey building and and run down the stairs you'll be down in a few minutes," says Russett. "But if you're at 60-storeys that's a long way down and if the stairs are packed with people it becomes a slow moving queue and that's what worries people." The Hong Kong codes mean nobody has to descend more than 15-20 floors by foot.

Scenarios have been played out on tall buildings to ascertain just how much time it takes for evacuation. A typical 50-storey office block of around 110 000 m2 can take between 45 minutes and one hour to evacuate using the stairs, compared with around 10-12 minutes using the passenger lifts.

With the drop off in the commercial sector a number of the big developers are beginning to move into the high spec, high-rise residential market. Hoare Lea is currently working on a number of residential schemes including one of 16-storeys and another of 23. Residential buildings in the UK must meet the functional requirements of the Building Regulations, including Approved Document B or other relevant guidance documents such as BS 5588. Alternative methods of compliance are acceptable, but are not common given that the burden of proof is placed on the design team However with commercial developers moving into the residential market, and tenants looking for better value for money, this situation is beginning to change in order to justify the premiums demanded for upmarket schemes.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet