John McAslan’s 8,500m2 Western Concourse at King’s Cross is transport architecture on an epic scale, returning the station to the grandeur of the golden age of trave. Just a shame about the glazing …

Next week a long-awaited new chapter in the history of King’s Cross station will begin. John McAslan + Partners’ new Western Concourse will finally be revealed and with it a significant milestone in the station’s massive £500m redevelopment programme will have been reached. The ambitious rebuilding project began in 2006 with refurbishment works at its brick eastern range, and has proceeded through several phases, one of which has included the restoration of Lewis Cubitt’s original train sheds, also set to finish this spring.

The entire project will complete next year when the 1972 “temporary” concourse is finally dismantled and replaced with a vast 7,000m2 public square designed by Stanton Williams Architects. But as by far the biggest and most ambitious new piece of architecture added to the station since it opened in 1852, it is the Western Concourse that represents the pinnacle of King’s Cross’ slow and painstaking rebirth. It is also the one component that holds the promise of rekindling the pioneering spirit of spectacle and grandeur with which the station was originally built.

At a mighty 8,424m2, the new concourse is over three times larger than the existing one

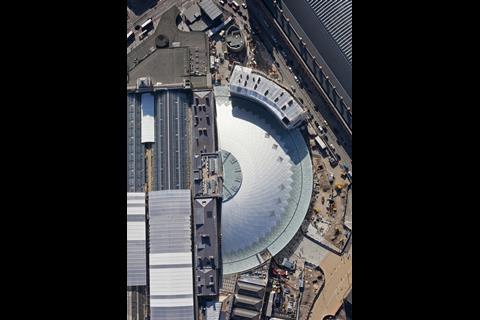

The Western Concourse is a gigantic semi-circular atrium that abuts the historic western facade of the station, filling a space previously occupied by a ramshackle assortment of railway service annexes and goods yards. Its curved footprint incorporates the rear arc of the adjacent Great Northern Hotel and is derived from the layout of the old semi-circular service route that was formerly located on the same spot.

At a mighty 8,424m2, the new concourse is over three times larger than the existing one. Its sweeping granite-floored, clear space is framed by the western facade on one side and a radial wedge of retail units on the other. The curved outer rim of the dome fills its remaining perimeter. A mezzanine level has been installed above the retail wing complete with cafes, lounges and a bridge link into the main train shed.

But the crowning glory (quite literally) of the entire composition is the swirling 130m-wide half-dome that forms the roof, the largest single-span station structure in Europe. Dotted along the curved edge of the concourse are 16 steel “tree” columns which bloom at their summits into an intricate tracery of beams that radiate across a sprawling shell of white perforated acoustic panels, reaching 20m high.

Across a precipitous uninterrupted span of 52m, the beams gather once again as they reach the concourse epicentre. They then peel away from the roof to converge as a webbed vortex “funnel” that plummets back to the ground. Daylight gushes in through the funnel via a gaping ocular skylight and also seeps in through a continuous band of glazing woven into the edge of the dome like a lace frill.

This is transport infrastructure on a spectacular scale. The swirling dynamism of the structure and space creates a steel whirlwind charged with an exhilarating force of energy and movement. It is an unashamedly theatrical and melodramatic set-piece, but one whose power lies in the rationalism and naked expressiveness of its structural form. Conceptually therefore it represents a stupendous futuristic reinvention of the Victorian ethos of civic grandeur through engineering prowess.

Strangely, despite its monochrome tones and geodesic roofscape, the new concourse is also an intrinsically organic space. The beams from the tree-like perimeter columns creep hungrily across the roof like a vine. And there is something womb-like in its curvaceous forms, the protective steel exoskeleton and the mezzanine bridge that snakes like an umbilical cord towards the main train shed.

This is transport infrastructure on a spectacular scale. The swirling dynamism of the structure and space creates a steel whirlwind charged with an exhilarating force of energy and movement.This organic quality reaches its climax in the retail wing. Entirely clad in a reptilian skin of 5.5 million tiny ceramic glazed tiles, the hooded structure crouches at the edge of the concourse as if about to pounce indignantly at the historic facade opposite. With its flowing curves, bulging profile and retro feel it also recalls the naturalistic sculptural forms of Eero Saarinen and his iconic sixties airport terminals.

This is transport infrastructure on a spectacular scale. The swirling dynamism of the structure and space creates a steel whirlwind charged with an exhilarating force of energy and movement

In fact, the congregational aspect and cavernous scale of the concourse make it feel more like an airport terminal than what we have come to expect from a train station. Its dramatic and aspirational character perfectly captures the sense of arrival, anticipation and celebration that was largely absent from the insipidly institutionalised transport infrastructure of much of the late 20th century, but helped craft the sense of wonder and romance that defined the golden age of travel that preceded it.

However, for all its bravado, the Western Concourse is at heart a building that has forged a sensitive relationship with the heritage that surrounds it. The concourse’s surging roof stops close to but not quite against the facade, allowing a tantalising tension between new and old that is reverential without being submissive.

The western range itself has been lovingly restored, with its brickwork cleaned and its interiors extensively refurbished.

The new ticket office, accessible directly from the Western Concourse, is a 360m3, five-bay, double-height hall with a magnificent row of spectacularly ornate cast iron brackets set below a gallery at its rear. Although there is an unfortunate anodyne pallor to the uniformly white-painted walls and ceiling, this remains a soaring, well-proportioned space that deftly recalls the classical grandeur of the original station.

Beside it, an undercroft complete with ticket barriers and new concrete piers has been carved into the block to provide direct level access from the concourse to the main train shed and platforms beyond.

The issue of access and circulation is the final piece in the new King’s Cross jigsaw and it is one handled with remarkable sophistication and efficiency. The concourse is almost fully permeable, with multiple entrances to the Underground station below and to the street outside, including one that will link to the new square. This equilibrium of access goes against the notion of a “main entrance”: powerfully, it is the concourse itself that becomes the symbolic “gateway” to the station and the destinations beyond.

This strategy also weaves a series of “accidental” spaces into the overall concourse volume, giving different personalities to individual areas. One of the most charismatic of these is the access to the suburban platforms just beyond the “umbilical” footbridge. This awkwardly shaped mini-concourse nestles underneath the protruding “skirt” at the edge of the dome and therefore allows the sprawling roof structure to swoop precipitously close to commuters below. This in turn creates a sense of intimacy and enclosure that is critical in helping to humanise a building conceived on a monumental scale.

Regrettably, however, there is one unavoidable fly in this rich ointment: the shortage of glazing in the concourse roof. Only 15% of the roof is glazed with the remainder comprising white perforated acoustic panels. McAslan explains that the amount of glass was determined by required daylighting levels and the need to mitigate excessive solar gain.

Environmentally prudent as this arrangement may be, it grievously undermines the concourse’s spatial impact and visual integrity. It is simply too difficult to believe that in this day and age it is technologically impossible to mitigate solar gain in glass buildings without covering them in louvres or replacing the glass.

Had the concourse roof been formed from a masonry structure, such as at the retail wing, then a more solid composition may well have been appropriate. But to create a skeletal, perforated structural frame of such exquisite geometric and aesthetic complexity and then submerge 85% of it underneath a metal case seems as mean and disingenuous as painting over stained-glass windows.

After being overshadowed by its glamorous neighbour St Pancras for so long, King’s Cross finally looks set to emerge as a revitalised 21st century terminus with a powerful new architectural identity of its own. With the hopeful promise of Euston being exorcised in the near future, this once drab corner of central London risks once again playing host to Europe’s most dazzling concentration of railway architecture. The Western Concourse is central to this transformation and it is without question a majestic space. But its oddly constricted glazing sadly stops it short of being a great one.

Project team

Client Network Rail

Architect John McAslan + Partners

Main contractor Vinci

Structural engineer Arup

Cost consultant Network Rail

Glass half empty?

Could more glass have been used on the roof of the new Western Concourse without irretrievably compromising its environmental performance? For Max Fordham, founder of the pioneering engineering consultancy that bears his name, the answer is an unequivocal yes. “It’s simply a question of passion and priority,” he explains. “The designer must prioritise what is important about the nature of the space and how much natural light it needs to work.” At King’s Cross he maintains that the amount of glazing is disappointing. “There are dozens of technical solutions available that could have dealt with glare and overheating without resorting to covering the glass in louvres. The concourse dome is 20m high, even if full glazing meant higher temperatures nearer the top; it’s only the conditions closer to ground level that people experience. Generally, there needs to be more room for invention when it comes to environmental design; that’s how natural daylight can give spaces the magical quality they need.”

1 Readers' comment