As we prepare for the Diamond Jubilee, Ike Ijeh takes a look at the influence the Queen, some of her forbears, and last, but by no means least, her eldest son, have had on British architecture

Over the next four days Britain will celebrate only the second Diamond Jubilee in almost 1,300 years of British monarchy. Today, the monarchy is still deeply embedded into the collective subconscious of British society and culture. From the Queen Elizabeth II Olympic Park to the Royal Assent that will be required before construction of the HS2 rail link can begin, its institutional influence is felt right across our urban fabric and national infrastructure.

But the Queen as an individual has never struck her subjects as being particularly interested in the realm of architecture. Despite being the world’s largest titular landowner (6.6 billion acres at last count) her long reign has provided scant evidence of anything more than a passing interest in the built environment. Constitutional discretion of course prevents the Queen from being vocal about anything, an inheritance that, for the time being at least, her eldest son appears to have disowned. But Prince Charles aside, one might be forgiven for assuming that architecture and the monarchy have very little in common.

Think again. The Queen may be a reluctant builder but throughout history her ancestors have utilised the unique concentration of power, privilege and patronage they enjoyed to reshape their kingdom and our environment in their chosen image.

Obviously over more than a millennium, architectural interest among various monarchs has varied sharply. Before he went mad, George III fancied himself as a gentleman draughtsman and even prepared designs for a country house under the tutelage of his favourite architect, Somerset House designer Sir William Chambers.

At the other extreme, despite having a large portion of the globe’s civic buildings and civil infrastructure named after her and presiding over the biggest urban and industrial upheaval this country has ever witnessed, for much of her long reign Queen Victoria herself exhibited little interest in anything other than grieving for her beloved dead husband.

Therefore to celebrate the Jubilee, Building has selected the three British monarchs who have arguably had the biggest personal and direct impact on our architectural heritage and compared their influence to that of our current Queen.

King William I

Reign: 1066-1087

Legacy: Tower of London, Windsor Castle, New Forest, 20+ castles, Lincoln, Durham, Chichester & Ely Cathedrals

To your average autocratic monarch, dictator, tyrant or property developer architecture serves as a useful physical manifestation of symbolic power. However, William the Conqueror was a calculating tactician and understood that architecture could also serve a clear strategic function: defence.

After overcoming the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Hastings, one of the king’s first policy decisions was to ensure that no other invader could do the same to him. So he set out building an impregnable phalanx of castles across the land and in so doing hard-wired the concept of fortification into the DNA of English architecture for the next 500 years.

Ironically, in the centuries that followed, much of the militaristic apparatus of this strategy, such as turrets, battlements, drawbridges and moats, became inextricably linked with an idyllic, highly romanticised view of medieval England whose mythological allure enthralled Victorian culture and still manages to captivate historians and Hollywood producers alike to this day.

In the frenzy of church and cathedral building the king initiated in order to cement his power among his newly appointed bishops, the king also introduced Romanesque architecture into England from the continent. Its English variant, the Norman style, gave life to some of Europe’s most spectacular ecclesiastical architecture and laid the foundations for the glories of the Gothic age that followed.

Finally, for relaxation the king liked hunting so ordered the planting of extensive woodland in Hampshire. Unfortunately for him two of his sons were killed there. Fortunately for us the New Forest is the largest remaining tract of unenclosed pastureland in crowded south-east England.

The Battle of Hastings has become a part of English folklore. William the Conqueror’s contribution to the fact that England has never been successfully invaded since 1066, and his transformation of our physical, as well as our political, landscape deserve a place there too.

King James I

Reign: 1603-1625

Legacy: Queen’s House Greenwich

The Stuarts were an incredibly cultured bunch. Charles I amassed Europe’s greatest art collection and had plans to transform Whitehall Palace into the biggest palace in the world (which were interrupted by the minor inconvenience of his beheading).

Between siring an estimated 18 illegitimate children, Charles II commissioned Wren to rebuild St Paul’s Cathedral and, in bequeathing several of London’s royal parks to its citizens established the libertarian principles for which the capital’s public realm has since become famous. Towards the end of the period, even William III, who was a military obsessive and considered every minute not spent pounding Frenchmen on a battlefield wasted, transformed Tudor Hampton Court into England’s royal version of Versailles.

But it was James I who changed the course of British cultural and architectural history forever. In 1616 he commissioned legendary English architect Inigo Jones to design a small palace for his Danish queen. The building Jones created came to be known as the Queen’s House in Greenwich and it was the first classical building in Britain.

To Jacobean eyes the whitewashed walls, unadorned roofline and orthogonal proportions of the Queen’s House might as well have been an extraterrestrial visitation. While our own royals may actively nurture a reputation for conservatism, it is incredible to think that 400 years ago it was the king who was at the forefront of pioneering futuristic and radical design.

It is hard to overstate the impact of the Queen’s House. In the early 17th century England was still clinging stubbornly to renaissance variations of what was essentially still the Gothic style while the rest of Europe was surging ahead with classicism. By the time the first brick for the Queen’s House was laid St Peter’s in Rome was already 110 years old. The Queen’s House dragged England kicking and screaming into the classical age and ultimately the modern world.

King George IV

Reign: 1820-1830

Legacy: Buckingham Palace, Trafalgar Square, Marble Arch, London’s West End, Regent’s Park, Brighton Pavilion, Regent’s Canal, London Zoo, King’s College, National Gallery

George IV was decadent, dissolute and debauched and led the kind of hedonistic, extravagant lifestyle that makes today’s oligarchs and celebrities look like choirboys. During his long stint as Prince of Wales and later Prince Regent he was the ultimate caricature of the playboy party prince and his enormous appetite for profligacy, gluttony and licentiousness enraged parliament, delighted satirists and allegedly earned him a monumentally regal 56-inch waist.

But despite the king’s best efforts, there was more to him than wine, women and gambling. He was not only a prolific patron of architecture and the arts but a paragon of fashion, style and taste. Moreover, in the Regency, he leant his title to one of the most enduring cultural movements of the 18th and 19th centuries and helped found both the National Gallery and King’s College. Even the famously irascible Duke of Wellington - far more at home on a battlefield than in a ballroom - dubbed him the “First Gentleman of Europe”.

Critical to the king’s architectural influence was his friendship with and patronage of the great Regency architect John Nash, arguably the most successful public private partnership in British construction history. Together they created Buckingham Palace, London’s Regent’s Park and its spectacular terraces, Regent Street and Brighton Pavilion and laid the foundations for an unbuilt summer palace that eventually became London Zoo.

By developing crown and commercial lands in central London the duo forged much of the urban character of the West End today and transformed London from a renaissance capital into an imperial metropolis. Paris is often considered the epitome of the formally planned classical city. But the sweeping urbanism of Haussmann’s Grand Boulevards was directly inspired by the parks, streets and terraces of Regency London produced 50 years earlier.

When the king died The Times, with barely concealed euphoria that today’s Murdoch-press would never dare emulate, declared: “There never was an individual less regretted by his fellow-creatures.” What they couldn’t possibly know at the time was that, despite his deep personal flaws, George IV had arguably had the biggest direct impact on English and European architecture and urbanism of any British monarch before him or since.

Queen Elizabeth II

Reign: 1952-present day

Legacy: Queen’s Gallery, Prince Charles

The Queen’s architectural skirmishes have been so few and far between that it is astonishing to consider that it was only her great-grandfather Edward VII who created the iconic urban backdrop to modern royal pageantry by commissioning Aston Webb to design Admiralty Arch, the current Mall and the East Front and balcony of Buckingham Palace.

In 1998 she appointed John Simpson to prepare suitably neo-classical designs for the new Queen’s Gallery, the first major extension to Buckingham Palace in almost 150 years. In 2006 she bowed to understandable pressure from tourism chiefs and TV networks by allowing Buckingham Palace to be illuminated (albeit dimly) every night by 59 low energy bulbs. Modernist architects were briefly galvanised when proposals for the restoration of St George’s Hall were invited after the 1992 Windsor Castle fire. But the mouth frothing ceased when an inevitably traditional design was chosen.

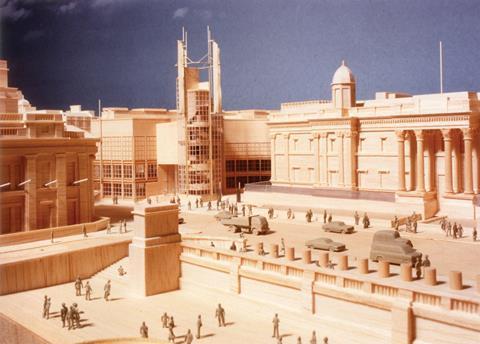

In fact the Queen’s biggest contribution to architecture may well prove to be her progeny. Prince Charles has become a towering, if divisive figure in British architectural politics over the past 40 years and has already had a significant impact on Britain’s built environment. He helped torpedo plans for Chelsea Barracks and the “carbuncle” once envisaged beside the National Gallery. Were it not for the nineties recession there is every chance that Paternoster Square today would look like the neo-classical oasis for which his active support helped gain planning permission.

Through his Prince’s Foundation he has promoted environmental awareness and a return to traditional architectural values. And in his developments at Poundbury and Sherford he has passionately resurrected the role of royal developer last occupied by George IV. Love him or loathe him, the Prince of Wales has honoured the memory of his forbears by proving once again that in the realm of architecture, monarchy still matters.

No comments yet