The 2008 liquidity crisis in the Middle East and then the Arab Spring did much to scare off UK firms. Now, a faster than expected recovery is drawing them back to Abu Dhabi, Qatar and particularly Dubai - which is seen as the business hub for the region

Dubai Cityscape - the emirate’s version of Mipim - was held recently and, for some, a worrying project was being trailed. Dubai, which built the world’s tallest tower, wants to build a replica of India’s Taj Mahal called Taj Arabia. It will be three times the size of the original, says its main financial backer. It will also be themed as the “new city of love”.

One reader of a Dubai news website was compelled to comment about the proposal. “Here we go again,” he said. “Now that the financial crisis is bottoming out, Dubai re-enters the silly and false boom era again.”

Jack Pringle, principal of architect Pringle Brandon Perkins & Will, is one man convinced the reader’s fears are misplaced. He opened an office in Dubai two years ago and was, he says, branded as mad for doing so. “When we opened, people said ‘Jack’s finally lost it,’” he remembers.

Pringle, a former RIBA president, ignored the criticism and stuck at it. He thinks he made the right call. “Dubai is recovering, much against everyone’s predictions. The mood music in Dubai is distinctly different to Europe. Dubai has a critical mass of schools, houses, hotels, restaurants - it is a place where people want to live.”

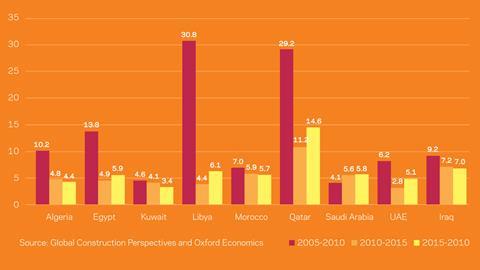

Dubai, it seems, is back. And, following the serious disruption surrounding the Arab Spring, so are large parts of the Middle East and North Africa, with Graham Robinson, director of think tank Global Construction Perspectives estimating there will be some £2.8 trillion worth of projects in the region to 2020. Growth sectors include housing - with an estimated one million homes in Saudi Arabia by 2014 - as well as energy, water, transportation and port infrastructure. The question is, with Qatar and Abu Dhabi thriving, and Dubai an ideal base for working around the much-changed Middle East, is it time UK firms were in on the action?

Cautious optimism

The 2008 liquidity crisis that engulfed Dubai in particular led to dozens of projects stopping virtually overnight, with abandoned cars at the city’s airport the symbol of the disaster as foreigners, previously deaf to the possibility of losing everything, lost a lot and fled home.

Pringle thinks there will be a bit more realism now. “It will have called time on some of the real lunacy that was going on. Wibbly wobbly buildings, rotating buildings, buildings underwater - as commercial property for offices they are just ridiculous.”

One firm that looked at Dubai as a base for the wider Middle East was demolition contractor Keltbray. It set up shop back in 2009 hoping that its track record over here - it brought down the unloved Pricewaterhouse Coopers towers that made way for the Shard at London Bridge - would help it over there. But 12 months ago the firm pulled out of what was its first overseas venture, citing a lack of work.

“The market was too flat, building sites were stopping,” says chief executive Brendan Kerr. “I wouldn’t rule out going back but there have to be more opportunities. We’ve got no work interest in the Middle East at the moment.”

Others, though, are less chastened. David Barwell is the chief executive of Aecom’s Middle East arm, which includes north Africa, where he is in charge of nearly 3,500 people from his base in Abu Dhabi. He has been there for four years after spending the previous 14 in Australia. Projects like Taj Arabia may create a sense of over-excitement, he says, but what they do show is that the Dubai market is returning. “Our view is that it’s cautiously recovering from a fairly low base. Dubai is a hub and business wants quality product.”

Abu Dhabi and Qatar - the great hope of the region given that it is staging the 2022 World Cup and spending billions of dollars in the process - are more cautious. Buildings tend to be less flashy in Abu Dhabi, Dubai’s richer but more conservative neighbour, while Qatar is building a new airport and metro and rail link to help it cope with holding the world’s biggest single sport event.

Infrastructure such as schools and hospitals are also needed, and Barwell says so acute is the schools problem in Qatar - children of oil and gas workers get first dibs on places - that ex-pats are flying in from Dubai or Abu Dhabi to spend the working week there

before flying back for the weekend. “The planes home on a Thursday night are chocablock,” he says.

Tony Douglas is, like Barwell, a relative newcomer to the region. In 2010 he left his role as chief operating officer at Laing O’Rourke to become a client again - he had previously been Heathrow airport’s managing director - by taking charge of the Abu Dhabi Ports Company. He has just overseen completion of the $7bn Khalifa port.

He thinks consultants have the upper hand when working in the Middle East. “They can limit the risk and they can put people in fairly quickly. They don’t have the same mobilisation costs as contractors.”

During his time at Laing O’Rourke he was out in the Middle East a lot - the firm had a joint venture with Abu Dhabi property developer Aldar - and says contractors need to identify a client and form a good relationship with them in order to get a steady flow of work. “The trick is for contractors to pick their targets, geography and clients wisely. In the heady days of 2006, 2007 they weren’t too careful.”

The last point is particularly pertinent due to the high number of contractors and consultants who went unpaid when the 2008 crisis struck. Terry Tommason, EC Harris’ head of property and social infrastructure in the Middle East, says: “Many professionals had bad experiences in the region when they got caught up in the 2008/2009 crash and will be understandably more cautious when considering opportunities in the region in future. Due diligence on clients is now a crucial factor in determining whether to bid or not.”

For Douglas, cosmopolitan Dubai is still a key, perhaps the key, market in the Middle East. “Dubai has disproportionately benefited from the Arab Spring because in the past the upper middle class from places like Egypt and Libya would move to the US or London. It’s very difficult to get in to the US now and London is very expensive. Dubai has benefited as result.”

Abu Dhabi, he says, takes things more slowly but is worth the wait. Saudi Arabia is booming, he adds, a point echoed by Aecom’s Barwell, which is working on the King Khalid Medical City in Dammam. “Saudi has a growing population and a need for infrastructure,” says Barwell. Headhunters, Douglas adds, are having difficulty finding people to run contracts there.

But Douglas warns that the upsurge in work in places like Dubai and Saudi Arabia, with the promise of more to come in Qatar and Abu Dhabi, means others around the world are eyeing the same opportunities. On Khalifa he worked with UK firms Halcrow and Atkins but he also worked with Korean, German and Australian companies and a host of local contractors.

“It’s not the world of five or 10 years ago. The amount of firms out here, it’s like the United Nations. If I tendered a 1bn dirham (£170m) contract a few years ago, I’d have got 40 bids but only three who could do it. Now three-quarters of the 40 could do it.”

Opportunities beyond Dubai

However, opportunities aren’t only to be found in the Gulf. Firms are using the stable Gulf states as bases to look for work in the wider region. From Dubai, architecture practice Pringle Brandon Perkins & Will has tabled bids for residential and hospitality schemes in the Lebanon and housing in Iraq. Both countries are firsts for the firm.

And Aukett Fitzroy Robinson, the UK’s only listed architect, has just moved its Middle East boss to Dubai from Abu Dhabi. Chief executive Nicholas Thompson says the firm is working in Syria and Iran as well, but is not sure about north Africa, the part of the region that saw the most dramatic changes as a result of the wave of revolution that began in December 2010. With shareholders to answer to, he has more reason than some to act cautiously. “In north Africa we will have to wait a little while,” he says. “We’re not big enough to have a position in every market and we prefer to be in markets we understand and that are more stable.”

Talk of north Africa tends to revolve around oil-rich Libya - the consensus is that French firms have the upper hand in places like Egypt, Tunisia and Algeria. “Libya is about timing,” says Douglas. “I wouldn’t rush in tomorrow morning, but it will become a serious opportunity in the next five years. I remember flying there with Laing O’Rourke in 2008 and the projects we were looking at were based around tourism, villas and hotels.”

But before the tourists come, the country needs stability and infrastructure - roads, bridges, ports, hospitals, schools. “Libya is a beautiful country but for various reasons has not presented itself as a destination in the way its neighbours like Tunisia and Morocco have done in the past,” says Tommason. “Libya will present opportunities but not for another two years.”

Barwell thinks stability in north Africa will return but it will be a slow process. “The instability has been driven by poor quality social infrastructure. People can build their way out of it. Housing, hospitals, schools - all of this is needed.” He adds: “Morocco and Tunisia are pretty small markets, Egypt is disorganised. Syria? Not for a long time. When you look at Libya it does have the oil wealth but it needs to organise itself.”

North Africa clearly has potential, but most opportunities are still some way off. However, there are definite signs of some sort of recovery in the Gulf region. And Dubai, which according to EC Harris, saw its economy grow 3% last year and is projected to grow 4.5% in 2012/13, is helping to lead that recovery.

The UK economy, by contrast, is expected to shrink by 0.4% this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. Jack Pringle knows where he would rather be. “Europe is stuck in the mud because of the euro which is a huge anchor dragging it back,” he says. “In the Middle East, they’re getting on.”

Return to Libya?

When contemplating working in Libya, top of companies’ agendas is the safety of their employees. “My company is taking the risk side of it very seriously,” says David Bucknall who has just stepped down as the chairman of Rider Levitt Bucknall. “You don’t want to be subjecting people to risks that you wouldn’t take yourself.”

Some companies, Bucknall says, will go in early to take advantage of the high rewards associated with greater risks but he predicts many will be more measured.

Aecom had more than 100 people working for it in Libya before the country was plunged into civil war. The firm ended up getting its staff on the Royal Navy frigate, HMS Cumberland, which picked up British citizens from Benghazi last year. “It was an evacuation,” says David Barwell.

“North Africa is characterised by government instability. It’s not an easy place to work. We have to have a guarantee of safety and commitment of payment.”

1 Readers' comment