From April 2018, landlords will no longer be able to let buildings with an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating of below E without demonstrating that all cost-effective measures to improve energy efficiency have been implemented. Adam Mactavish and Richard Quartermaine of Sweett Group and Charles Woollam of SIAM examine the implications of this policy

01 / WHAT IS PLANNED?

Under the Energy Act 2011 the government is set to introduce regulations to drive take-up of cost-effective energy efficiency measures in both domestic and non-domestic sectors. Landlords will have to comply with these regulations before letting their properties.

The regulations are still in preparation, but the briefing on the topic from the Department for Energy and Climate Change states: “… from April 2018, private rented properties must be brought up to a minimum energy efficiency rating of E. This provision will make it unlawful to rent out a house or business premises that does not reach this minimum standard.

“This requirement is subject to there being no upfront financial cost to landlords. Therefore, landlords will have fulfilled the requirement if they have either reached E or carried out the maximum package of measures funded under the Green Deal and/or ECO (even if this does not take them up to an E rating).”

The government estimates that about 18% of UK non-domestic properties are F or G rated. SIAM’s analysis of more than £3.5bn of investment-grade property suggests that about 13%of capital is invested in these buildings.

Owners of F or G-rated buildings will need to undertake measures to improve the performance of their properties until they achieve at least E ratings or until they can demonstrate that further measures are not cost effective. In this context, “cost effective” means that the energy efficiency measure would meet the Green Deal’s “golden rule” that the net savings over its life would be sufficient to at least repay a Green Deal loan.

These regulations will form part of a suite of measures aimed at driving greater energy efficiency in buildings - others include the CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme and planned changes to the consequential improvements elements of Part L.

There are significant benefits arising from such regulations in the form of energy savings and reduced carbon emissions, but here we are more concerned with the impact on investors in non-domestic properties.

02 / IMPLICATIONS

The increasing focus on building performance reflects the widely accepted view that the property sector can make significant and cost-effective energy efficiency improvements, thereby reducing demand for heat and power in line with the national energy strategy. Once the Green Deal “carrot” is on the table, landlords can face the threat of being unable to let their properties if they refuse to eat it!

While the Green Deal lends itself well to owner-occupiers, it is more complex in situations that involve a landlord and a tenant. Under current convention, it is the tenant who would benefit from energy savings without necessarily being prepared to take on the cost of improvements carried out before the start of their lease. This would leave landlords with all the costs and none of the savings, and it is far from certain that they will be rewarded with higher rents for more energy-efficient properties. Even if landlords are able to pass on the costs of Green Deal-backed investments to occupiers, they will remain liable to maintain payments during any periods when the building is vacant.

Owners of F or G rated properties, which are common in most portfolios, will need to consider the impact of the regulations on their assets and in particular the relative performance of their buildings compared with peers.

Some of the key questions are:

- Which properties within their portfolio are currently F or G rated, or have the potential to become F or G rated before 2018?

- What measures are likely to be required to achieve a higher rating?

- How much might it cost to implement these measures?

- Will the costs be absorbed in a general refurbishment or at marginal additional cost?

- What are the lease terms for these buildings?

- Will some of the measures be covered by dilapidations?

- Are there clauses that enable the landlord to pass on costs for compliance with legislation?

- Are the impacts on your building likely to be any more or less significant than for other similar buildings in the local market?

- What impact might different improvement options have on the value of the building and its appeal in the local market?

These factors may also be a significant consideration in the acquisition of assets and should be included as part of the due diligence process as any significant expenditure may need to be reflected in transaction prices.

Since the extent of the obligation to make improvements is linked to energy savings and there is no direct correlation between energy costs and property values, the new regulations will affect some buildings more than others, and could even become a blight on some types of buildings.

03 / KEY RISKS FOR LANDLORDS

For many properties, if not most, the investment required to meet a minimum E rating will be negligible in the context of overall asset value. However, for properties where current energy performance is poor, it may be possible to make significant improvements that are cost effective under the golden rule but nonetheless require significant capital investment.

These poorly performing buildings are typically those with a little history of investment in maintenance or plant replacement, in part because the business case for doing so is weak. In these cases, mandatory investment in improvements that might otherwise have been deferred indefinitely may have an impact on asset value.

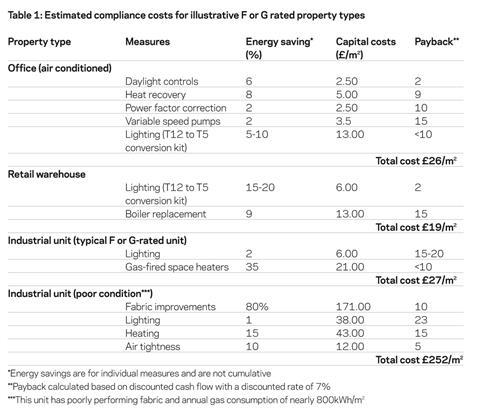

To assess which buildings are likely to be most significantly affected, we have estimated the potential compliance costs for which a landlord might be liable for different types of property (see Table 1). These costs are based on the energy consumption of an F or G rated property of each type and an assessment of the measures that would need to be implemented to either improve the building’s performance to at least an E rating or, if this rating cannot be achieved, implement all the measures that are consistent with the golden rule.

Cost data is taken from Sweett Group’s research and is based on real buildings and EPC modelling of the impacts of different measures. The findings are only illustrative but provide a good indication of the nature and costs associated with measures that might be required by regulations on minimum energy standards.

Table 1 (below) shows that for some buildings there are real opportunities to make large cuts in energy consumption and associated carbon emissions. Associated costs are in the range of £19-£27/m2 for three of the buildings assessed. However, in some instances, the costs involved can be much higher, for example, where the current building fabric has poor thermal performance.1

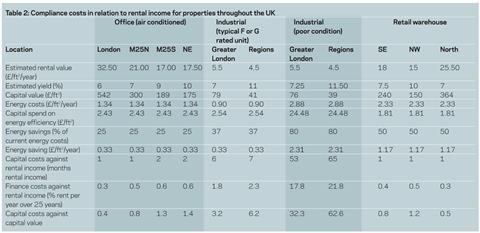

The materiality of these costs for landlords relates to the rental income they can expect from each property. As a rule of thumb, compliance costs equivalent to more than, say, six months’ rent may be considered “significant” and costs of more than one year’s rent would be a serious consideration.

Table 2 presents these compliance costs in the context of current rents achievable for buildings of this sort in different parts of the UK. The results show that for buildings that can secure higher rents (for example office and retail space) and that do not require significant fabric replacement, the impact of regulations may be relatively minor. However, for asset types where rental levels are lower, the implications are more significant - in this example, industrial units in lower rent areas.

For industrial buildings that are in poor condition, with ageing fabric, the impact of regulations could be significant. In these units it may be necessary to invest the equivalent of up to five years’ rent or incur finance costs of about 20% of rental income.

Occupiers of F or G rated buildings will benefit from significantly reduced energy costs, but may still be unwilling to contribute towards repayments if they have the option of choosing an equally efficient building without Green Deal financing. This is because a key impact of the regulations will be to enforce action on energy efficiency that was not previously being driven by market forces owing to a lack of interest in (and availability of) data on energy costs. Landlords with inefficient properties have often been able to secure rents comparable to those with lower energy consumption. They will now have to make investments to improve their performance, but may find it difficult to pass these costs on to occupiers. Those landlords with buildings with EPC ratings of E and above in 2018 will be able to maintain their returns and will benefit from a level playing field.

Although the regulations do not come into force until 2018, it is likely that impacts will be seen much sooner. There is already greater risk attached to F and G rated buildings and, in some cases, current values will be adjusted to reflect the new risk.

Little information has been released about how the government will frame the detailed regulations, but the uncertainty is already sufficient to make it unwise to buy or lease F and G rated buildings without investigating the full implications of the proposed regulations.

Properties let on long leases will not be immune as tenants that are unable to dispose of surplus accommodation without incurring compliance costs may argue at rent reviews that rents for F and G rated buildings should be less than rents for better rated buildings which, until now, have been of equal value.

1 For the industrial unit, fabric performance is less relevant for the 35-40% of these buildings where the main warehouse area is unheated

04 / IMPACT ON THE CONSTRUCTION SECTOR

The Green Deal, together with the inability to let F or G rated properties, will impact on the nature and scale of refurbishment projects.

Where investment in energy efficiency is required to achieve compliance, landlords may choose to bring forward larger scale refurbishment activities to achieve savings by doing both at the same time.

However, for most building types the measures required to move a building above an F rating involve upgrades to HVAC plant, lighting and controls. It is therefore likely that the main beneficiaries will be manufacturers, suppliers and energy contractors rather than the wider construction sector.

Exceptions may be seen in buildings with very poor fabric performance and associated high energy costs. In these cases there may be a need for investment in new cladding and roof systems to achieve the necessary improvements in energy performance.

05 / SUMMARY

A significant proportion of buildings in the private non-domestic rented sector have EPC ratings of F or G. For many of these buildings the costs of improving performance will be absorbed within planned building improvements and replacement cycles and for many others, the costs of compliance will be negligible in the context of overall rental income.

For still more, the cost of compliance will be met by occupiers (who will receive compensating benefits in the form of lower energy bills). However, there will be some properties, including heated industrial units in areas with relatively low rents, where significant costs will sit with the landlords. This may undermine the appeal of some F and G rated buildings as investment propositions.

The buildings that will be most significantly affected are those where there is a supply of more energy efficient properties in the locality, as owners of these buildings will find it most difficult to recover the additional costs incurred.

However, we should remember that, until now, owners of these properties have been able to take advantage of occupiers’ lack of interest in energy performance to secure the same rents as owners of more efficient buildings.

The use of EPC ratings to enforce minimum standards on the private rented sector is a huge step in the management of existing buildings. Landlords should also keep in mind that the UK’s energy and climate change targets are unlikely to be met simply by addressing F or G rated properties and further measures (perhaps restrictions on renting E-rated properties) can be expected in the future. They should also remember that a building rated as D today may be rated as F when its energy performance is next assessed in 2022.

Many investors and their tenants do not yet assess sustainability-related risks to their property portfolios. This is because the financial impacts have been difficult to quantify and are uncertain. The Energy Act introduces a tangible risk and all owners and their occupiers should now consider the implications for their properties. In most cases they will be able to heave a sigh of relief (for now), but a few are in for a nasty surprise.

1 Readers' comment