The project was divided into three distinct phases, beginning with the Jumeirah Beach hotel, then the Wild Wadi Aquapark, followed by the Burj Al Arab hotel. Construction management was chosen as the best way of ensuring effective cost control and speed of building which meant the work was broken down into manageable procurement packages, each of which was tendered separately.

The scheme has generally been completed to British Standards with National Engineering Specification used for the mechanical services. For example, the fire protection sprinklers in the Burj Al Arab were designed to NFPA codes as these were considered to be more appropriate.

Under Dubai law, an entirely foreign conglomerate cannot carry out projects, so all contractors are required to have a local company as a partner or sponsor. In general, this emphasis on partnering worked well throughout the project. Design work on site began in January 1994 and piling for the Jumeirah Beach hotel began later that year. By mid-1995 floors were being completed at the rate of one per week.

Throughout the project the British engineers had to get to grips with a climate that was very different to the one that most of them were used to. British Standards applied to most of the project, so safety precautions such as boots and safety hats were required despite high humidity and summer temperatures of up to 45°C.

These conditions affected materials, and the concrete in particular was very different from that used in the UK. It also had to be sprayed constantly to prevent it setting too quickly.

From the outset there was a major emphasis on maximising local input, from the 4000 strong labour force to the specialist technologies and equipment. The religious requirements of the workforce had to be accommodated in the scheduling, however, as there was a high percentage of Muslims, all of whom stopped work five times a day for prayers.

Jumeirah Beach was built adjacent to the existing Chicago Beach hotel, which was later demolished to make room for the Wild Wadi Aquapark. Its style was inspired by the Arabian seafaring tradition, with an external shape echoing the form of a huge breaking wave. This was achieved by curving the building in both plan and elevation views, combined with the use of shimmering blue glazing and cladding.

The structure is essentially concrete and steel, having used 45 660 m3 of concrete and 5831 tonnes of reinforcing steel. At its highest point the hotel reaches 92·5 m and is 298 m long stretching along the shore from east to west. The length is contrasted by a width of just 14 m, giving the appearance of a slim and delicate structure from a distance.

This has the advantage that every room has a sea view because there is a single row of suites offering panoramic views through floor to ceiling height, low emissivity double glazing.

Jumeirah Beach has 600 guestrooms and suites, nine themed bars and restaurants and a number of other facilities. These include a three-storey conference centre offering 2500 m² of function space with state of the art exhibition and banqueting facilities and 19 richly decorated Arabian Villas with a six-star luxury rating. These are sited in Arabic landscaped gardens, each villa having its own private pool. There is also a two-storey sports centre and health suite with a range of facilities, a 53 hectare marina with a seafood restaurant and a themed beach restaurant. Children can occupy themselves in the 'Kid's Club', with three swimming pools, seven tennis courts and an adventure play area.

An Arabian tower

Nevertheless, the Burj Al Arab is, without a doubt, the star of the show and forms the main focus of the whole resort.

"When I arrived in 1993 I was confronted with the architectural wild west," recalls W S Atkins project architect Tom Wright. "Buildings were being designed by architects from India and Europe in very funny styles. We had to design a building that would become a symbol not of Dubai's past but of its future." This was to be the sail-shaped Burj Al Arab as a "symbol of luxury yachting of the future".

Wright also decided to locate the hotel 290 m out to sea, on a triangular, landscaped artificial island to avoid casting a shadow on the Jumeirah beach and the adjacent beach. "It also answered another part of the iconic brief; another bit of wow factor," he comments.

"Forming the island created a considerable challenge," said Ian Heijne of W S Atkins Water. "The area is host to the Shamal, a seasonal wind quite capable of generating dangerous waves. The island had to be high enough to stay dry but not so large as to detract from the tower." There was also some concern about how the island might affect the coastline and whether sand might build up into a spit joining the island and the shore. To answer these questions information on wind and wave behaviour was fed into a nearshore spectral wave model to predict the effects of wave climate on the island. A 1:50 scale model built by H R Wallingford was used to test for erosion and overtopping.

Covering an area of 6000 m2, the island was constructed in 18 months using 2·7m thick reinforced concrete, supported on 250 bored piles founded on the underlying carbonate rock 45 m below sea level. As the building design also called for three basements, substantial excavation of the seabed was necessary before the construction of the structure could start.

The choice of concrete was critical because there are high concentrations of chlorides and sulphates in the Arabian Gulf coastal regions, as well as large temperature swings between day and night, and wide variations in humidity. Consequently, high quality, dense, low permeability concretes were specified with 60 mm or 75 mm reinforcement. Below ground, silica fume reinforcements and membranes enhanced durability.

The island is protected by special hollow concrete armour units, called SHED units, approximately 1·3m3 with a large void. These present a perforated sloping surface to the sea that absorbs the impact of the waves without throwing water onto the island. Although Dubai itself does not have a high earthquake risk it is adjacent to an area of moderate risk and the Building Research Establishment supplied recommendations on earthquake loadings.

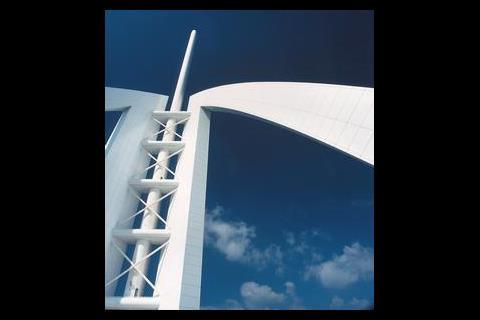

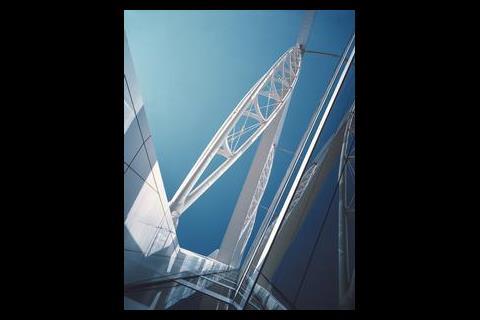

The building itself is also triangular, with two wings spread in a V from a vast 'mast', while the space between them is enclosed in a massive atrium by a curving 'sail' of Teflon-coated fibreglass. The 'sail' facade, measuring 54 m x 180 m, was the first structure of its size to be made of a double-skinned, Teflon-coated woven fibreglass screen (see factfile).

The Burj Al Arab is taller than the Eiffel Tower, the Post Office Tower will fit in the atrium and the mast is larger than a Saturn V rocket.

A massive steel exoskeleton steadies the tower against seismic loads and the wind. This V-shaped frame wraps around a second V, the reinforced concrete tower containing the hotel rooms and lobbies. The two structures connect along a shored, reinforced concrete spine at the base of the V, and at two points along the curving atrium wall.

Each of the pea-pod shaped diagonal trusses on the side of the building is 85·6m long (the length of a football pitch) and weighs 120 tonnes – equivalent to 20 double decker buses. The highest truss took a day to lift into place.

The trusses were built 15 km from the site and brought by road on huge 80 wheel lorries, which had to be specially imported from South Africa. One of the few advantages to working in a remote area some way from the city centre was the ability to close the six-lane main highway for a day to achieve this.

It is different, stylish, unique and makes a strong statement about where Dubai is going and what it aims to be: modern and vibrant. It makes an equally strong statement about the standards of British engineering.

Thermal fabric wall

The thermal fabric wall is two skins of ptfe coated fibreglass separated by an air gap of approximately 500 mm and pre-tensioned over a series of trussed arches. These arches span up to 50 m between the outer bedroom wings of the hotel which frame the atrium, and are aligned with the vertical geometry of the building. The double-curved membrane panels take positive wind pressures by spanning from truss to truss and negative wind pressures by spanning sideways. The trussed arches, which can extend out from the supports by up to 13 m, are supported vertically at the 18 and 26 floors by a series of 52 mm diameter cross-braced macaloy bars. Girders at these floors transfer the load to the core structures. The macaloy bars are anchored at level one to a substantial entrance girder, which is tied to the lower basement structure. The resulting form is entirely appropriate for the building and its function with the fabric reducing solar gain into the atrium and providing an effective diffused light quality. by David Dexter, W S AtkinsSource

Building Sustainable Design