But many companies in building services have begun to deal with these questions, and are successfully tackling the major business challenge of changing the way they work.

BSJ went to visit S&P Coils (SPC), a small manufacturer based in Leicester. Not perhaps the most glamorous place to go looking for the secrets of managing change. However SPC has done all these things gradually over the course of around four years, and in doing so has doubled profits, cut delivery times by 75%, reduced stock by 33% and been able to invest in the latest production equipment as a result.

Operations director, Kelvin Davinson, says: "I joined the company about five years ago. It had been doing quite well in terms of profit. But the directors wanted to move the company forward." Davinson says that SPC was a traditional manufacturing company, with a traditional way of working. "We really relied on the supervisor level on the shop floor to make all the decisions about what was manufactured and when. That was how it was done, and at that time we probably didn't have the level of control over our manufacturing that we would have liked."

The first task when looking to improve is to find out where you stand now. As far as SPC was concerned their position four years ago was one shared by many UK manufacturers: large amounts of stock; lots of work in progress on the shop floor; and things being done because they had always been done that way.

"We made some decisions based on our whole business strategy. One was that we wanted to make to order. To do that we had to make items quicker, especially during our busy periods," says Davinson.

He began by looking at the strengths of the organisation. "One element we are particularly strong on is staff job knowledge. We just had to harness that information and make people review what they were doing, not simply accept that this is the way they have worked for so long.

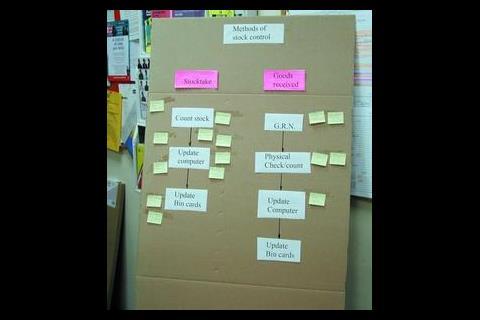

The company used the technique of process mapping. This involves examining each business process step-by-step and, in the case of SPC, literally creating maps of the way things are done.

We had to challenge people to think about what they could do better. We needed to involve people in the changes, to give them the opportunity

Kelvin Davinson

Davinson says that the process maps were particularly revealing: "People's perception of what's actually going on and happening is often different to the reality of the work. When we started doing the process maps it was quite surprising."

He cites the example of the ordering process where the account number was checked on three occasions by different members of the team. This was immediately cut to one checking process.

One other method Davinson employed was the creation of action teams. "These were made up of people from across the company, not just the shop floor so they were cross-functional. The idea of action teams is that they're not just talking shops. Each one is presented with a problem, finds the solution and implements it. The teams make it happen."

One of the most significant steps for SPC was to change the layout of the organisation, including the shop floor. At this point, the company introduced other aspects of Best Practice such as kanban and just-in-time manufacturing. "We began working on lean manufacturing principles – taking out non-value-added activities where we could. Our lead times have now been reduced by a good 33% from where we started three years ago," explains Davinson.

Changes to production methods meant changes to the way many of the staff worked. "Our supervisors used to have to make sure everyone was working on the correct components, at the right time. Once we introduced just-in-time, the only components available were the correct ones. So the whole emphasis of the supervisors' job changed."

Now the supervisors' role is not one of managing the manufacturing process from start to finish. They are involved in management meetings, where daily targets are agreed. They also organise the workforce overtime requirements because, as Davinson points out "they know best what is required."

For those employees on the shop floor, the new way of working has meant further training. The emphasis is on multi-skilling, so that workers can easily be moved from one task to another as workflow demands. "We have put a lot of effort into training, and most people on the shop floor now have between three and five key skills," says Davinson.

Davinson says that SPC has changed its relationship with clients as a result of this culture shift. "For our unitary products, we can now say that if we are 24 hours late in dispatching we give them away. I think the initial response from clients was that they still asked for products way ahead of their own deadlines because they don't think the industry can do things on time. But more customers are leaving their orders till later."

Significantly, one of SPC's largest customers was already using best practice techniques, and had created a league table of its suppliers. Davinson says that over the course of three years, SPC made its way from 'near the bottom' right to the top.

At the other side of the manufacturing process, SPC's relationship with its own suppliers has changed. "We visited all our suppliers when we started this process and explained what we wanted to achieve going forward. We said to them that if we're more profitable and busier, they can gain too. The majority have joined in without any real problems," says Davinson.

Cultural change: some key points to bear in mind

Changing the way an entire company thinks is one of the most difficult management tasks. The lessons learned by S&P Coils (SPC) could apply to just about any organisation. 1. Before you change, find out where you’re starting from. Process mapping proved very revealing – do you really know what happens when customers phone in?2. Involve everyone. Unless the entire staff can be engaged, there will be no commitment to making change, which will probably be viewed as just another management ploy. 3. There must be commitment at the top. The directors can sometimes be the most difficult to manage when it comes to new thinking, unless they can really see a benefit. “The directors of SPC wanted the business to move forward, and realised that they had to change culture and process to achieve this,” says Kelvin Davinson SPC’s operations director. 4. Remember that there is no finishing point. Change is continuous and once improvements start to be made it should become an organisation-wide habit. 5. Talk to suppliers and customers about what you aim to achieve. They may have been through the process themselves, or be willing to join in making changes which will assist you.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet