Rust is the chink in a tank’s armour, so King Shaw Associates made sure there was no condensation in the Tank Museum’s new exhibition space

King Shaw Associates decided to keep things simple in its services design for the new Tank Story exhibition space at the Tank Museum in Bovington, Dorset.

The museum is home to the largest collection of tanks in the world. Like so many British military attractions, there is a somber and respectful tone, alongside tongue firmly in cheek. A commemorative statue stands outside reminding visitors of the human cost of warfare, close to the children’s play area.

However, arrive at the right time of day and you could find yourself greeted by a massive Chieftain tank circuiting the tank arena, pirate flag billowing in the wind to the strains of the Phantom of the Opera. It’s a unique experience.

The museum was set up in the 1920s and has proved a lure for tank and warfare enthusiasts for decades. However, as times have changed the museum has found itself in need of a more competitive footing. The vehicles themselves were never built for posterity, leaving the museum owners with the added concern of preserving the exhibits beyond their natural lifespan.

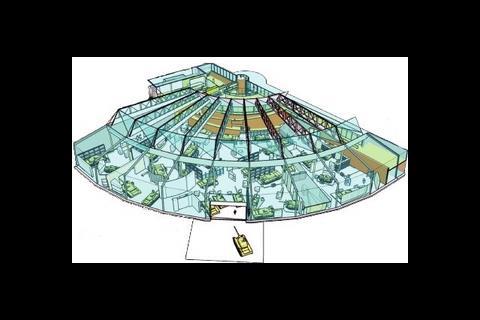

With so many vehicles and limited space, the museum trustees decided improve the museum facilities, the crowning jewel of which would a brand new exhibition space designed to showcase and preserve these military treasures.

The exhibition centre began life over a decade ago. Museum director Richard Smith says: “The Discovery Centre was home to the main collection. It’s basically an old tank shed that’s had things tagged on to it over time. The tank geeks absolutely adore it but it is very 1970s. Exhibit plus explanatory plaque. We had so many vehicles that it had a bit of a car park feel to it.”

The Discovery Centre has that old vehicle museum feel to it -an intense smell of diesel, flat florescent lighting and the feeling that you’re about to bump into a busload of school children armed with handouts and packed lunches.

The centre was full of vehicles, while others have languished in equally crammed sheds or out in the open protected only by tarpaulin. Something had to be done to improve the visitors experience and ensure these vehicles survived.

Bovington has been a base of military operations since the Great War. Legend has it that the museum was inspired by writer Rudyard Kipling. He was reported to have seen a collection of tanks left rusting in a Bovington field and suggested that something should be done to retain them for posterity. There is no way to verify the myth, and the story has probably been embellished over the years in the telling, but according Smith, the date and the story is good enough for them.

Back in the early fifties, the public was admitted for free, and the collection was operated by the Ministry of Defence. This continued up until the 1980s and according to Smith there has been an ongoing process since then of clarifying the relationship between the museum as a body and the MoD. The museum had to obtain the lease for the land before it could upgrade the facilities.

Smith says the move towards a more commercial visitor's experience has been an attempt to raise the museum's game as a tourist attraction, and making the museum more self sustainable.

Smith says “It's no longer just an army collection, it's a visitor attraction. We have to compete with more attractions and because we charge we have to make that an appealing experience to potential visitors.”

After obtaining the lease, the museum applied for funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, which was granted in 2005. The museum received a capital grant of £9.6m.

King Shaw Associates became involved in the project in 2002 as the masterplan was still being compiled and with an eye for how they could preserve the entire collection.

Doug King says: “We wanted to benefit every tank in the collection. We did a complete stocktake of all the tanks and their decay. There was a back log of 30 years’ maintenance, and there were some wrecks.”

King identified early on that the chief problem would be the visitors themselves, more precisely the condensation they would fill the room with by merely breathing.

King says that the firm’s approach the problem was instinctive, rather than looking for the “least worst option”.

“The right solution will appear if you think about the problem long enough,” says King. “We spent ages crawling over the museum and understanding what was going on and what we saw were bad examples of bimetallic corrosion.”

We argued for months that these are outdoor fighting vehicles and that is how they should be seen. We believed this could be achieved with daylight using the roof design

Bimetallic corrosion is an electrolytic reaction between dissimilar metals. Painting the tanks had prevented the steel vehicles from rusting, but where brass fittings were attached there was bimetallic corrosion. The solution King identified was to prevent this reaction from happening at all, by heating the tanks above dew point.

“It all suddenly made sense,” says King. “To preserve these vehicles in the new space, we needed to stop condensation getting on the tanks. How do we do that? We make the tanks warm so they don't get below dew point. You've got big tanks and a big room, so using air conditioning wasn’t going to do it. The only way was radiant heat.”

The new exhibition space was designed with a system of overhead radiant heating panels. These raise the surface temperature of the tank hulls above dew point and ensure that condensation, and therefore corrosion, does not occur. The panels also provide energy-efficient heating for the space, especially useful in the winter months when the temperature, and energy consumption levels, can be reduced.

Displacement ventilation carries the moisture in the air away quickly. Fresh air is introduced via large underground concrete ducts. These ducts were designed specifically so they could carry the massive load of the tanks on the display hall floor.

Steve Caulfield, director at King Shaw, says the practice designed the system to be adaptable, to match visitor numbers.

“When you have a heavy visitor flow,” says Caulfield “you have to ventilate for more people. We also put heating batteries on the underground vent system to enable the air to quickly heat or adapt the environment. There’s constant heating from the radiant panels at high levels and this quick response system from the under floor heating that acts as ventilation and another form of heating, with the fresh air coming from the underground ducts.”

Another key aspect to the design of the space is the use of light. Unhappy with the “flat lighting” in the Discovery Centre, King Shaw worked closely with architect Kennedy O’Callaghan on the design of the roof. However, he did have to fight the exhibition designers on how to light the space.

Kings says: “There was no sense of depth and these are tactile objects. Originally the exhibition designers wanted complete black out and complete control over the lighting, but that would have cost a fortune just to light the space. We argued for months that these are outdoor fighting vehicles and that is how they should be seen. We believed this could be achieved with daylight so we asked for the opportunity to work with the architect to design the roof properly.”

The narrow roof apertures create directional light, which is diffused by interreflections from the soffit. The roof form is aligned so that the sun is always shining on the backs of the roofs rather than in through the lights, apart from later in the day and after visitor hours. King claims that whatever time of day or year it is, the quality of light is always the same.

According to King, 60% of the light is directional light and 40% is diffuse light. Which is roughly the same as a moderately sunny say outside. He claims this gives the tanks much more of a dynamic presence.

King says “We originally considered a glazed barrel vault. The problem with that is when the sun reaches the apex and the sun shines in. We designed a series of reflectors that would sit inside the barrel vault each one angled slightly differently. This would have mean that wherever the light came in, it would be reflected in the same direction to replicate these narrow aperture roof lights. That was some serious design and it would have been superb. The first time anyone used variable pitch louvres to take diffuse light and turn it into directional light. Maybe we’ll keep it on reserve and use it another time.”

King Shaw also upgraded the ancillary buildings which house the Tank regalia. These were reclad, insulated and made airtight. This was particularly important for the archives, which houses everything from regiment flags and swords to uniforms and excavated pieces of machinery. King Shaw put in a climate-control system which keeps the humidity levels up in order to preserve the archived materials.

Some of this regalia is now on display throughout the Tank Story exhibit itself, something that was not possible with the limited floor space of the Discovery Centre.

According to King, the Lottery Funding was dependent on the conservation of the tanks being an ongoing process. The Tank Story has freed up space in the Discovery Centre, space that could be occupied by vehicles in the storage sheds.

“It’s a continuous tide of tanks,” exclaims King. “This was key to the Heritage Lottery Funding. They like access and ongoing conservation. This is an expensive building but there is scope to move more tanks from the sheds and into the display areas.

King believes that while the design of the Tank Story is the best system and the most sustainable solution it may not achieve a top DEC rating when the first year of readings are available next year.

“The exhibition space is mechanically ventilated and we found out that DECs are purposely biased towards natural ventilation. That’s a real bugbear with me, because in this context mechanical ventilation was the best solution. Clients want option appraisals that offer them the sexy option in today’s market, what is seen to be green today. Anything that we judge as sustainable today has to still be operation in 2050. I am confident that the Tank Story will be.”

Rescued from rust

Bovington has been a base of military operations since the First World War. The story goes that the museum, which was set up in the 1920s, was inspired by writer Rudyard Kipling. He was reported to have seen a collection of tanks left rusting in a Bovington field and suggested that something should be done to retain them for posterity.

In the early fifties, the public was admitted for free, and the collection was operated by the Ministry of Defence. This continued until the 1980s and, according to museum director Richard Smith, there has been an ongoing process since then to clarify the relationship between the museum as a body and the MoD. The museum had to obtain the lease for the land before it could upgrade the facilities.

It then applied to the Heritage Lottery Fund, which gave it a grant of £9.6m in 2005.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet