At only 15m wide, you certainly wouldn't expect to find a building which contained not only classrooms, admin offices and dressing rooms, but also three theatres, workshops, large rehearsal rooms and a cafe. And there are only four floors.

The first thing which strikes the visitor is that in spite of its size, the RADA building doesn't feel cramped. The main entrance and stairwells are naturally lit, making full use of a central courtyard to maximise the daylight available. There is also a sense of the old rubbing shoulders with the new. While busts of venerable playwrights and theatrical tzars stare down from enclaves in the stairwell, the cafe bar is as modern in design as any other you'll find in West End London.

But once the architect had made as much of the available space, it was down to building services consultants Roger Preston & Partners to fit in all the services; and make them work effectively. Consulting engineer Martin Wood, explains: "The original brief to the architect could have ended up with the Academy moving to another site. But as they could not find another suitable location they decided to maintain their presence on site, although it's very compact."

Layout

On the ground floor there are administration offices, and a cafe. Beneath this is a large loading area, accessed from the rear of the building, along with two workshops containing woodworking, welding and scenery painting facilities. A large service elevator has been installed, big enough to contain theatrical backdrops.

The school has around ten classrooms, including small 'rehearsal' rooms which are kept relatively bare. Other facilities include a laundry room with washing machines and tumble driers; costume storage spaces; and downstairs in the old vaults the space has been converted to dressing rooms.

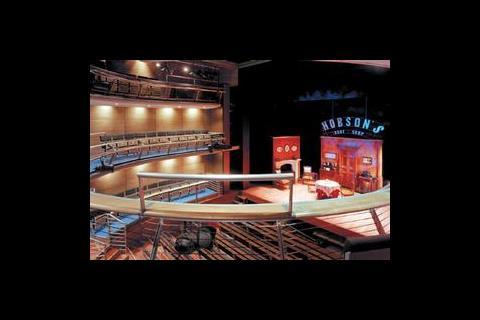

There are three theatres. The John Geilgud studio seats 60; the George Bernard Shaw seats 100; and the Jerwood Vanbrugh which has capacity for 200. All are open to the public.

The challenges

The services engineers faced a number of challenges on this job, all of them impacting on the design and installation of the various services.

Firstly, the small size of the building limited the number of services which could be installed, and their positioning. Throughout the project Wood and his team were faced with the problem of keeping ceiling areas clear to maximise the floor to ceiling height so that props and backdrops could be moved about easily.

Starting in the basement area, all the services were put to one side on the wall. These include drainage; power; communications; fire alarm; compressed air for operating workshop equipment, and sprinklers. "This is where scenery is built for the theatres, so we couldn't afford to lose any clearance at the top," says Wood. Also in this area are workshops where students learn how to make scenery and props. This involves, among other things, woodwork, welding and painting.

Beneath the loading area is a 120 m3 water storage tank for the emergency sprinkler system. There was simply nowhere else to access the water, and nowhere else to store it.

Moving upstairs to the George Bernard Shaw theatre, this is the first of the entirely enclosed areas. Again, because of requirements for stage sets, the ceiling area had to be kept clear of services. Pipework runs along the wall where possible. In control rooms for sound and light, at the back of the theatre, space is at a premium. The rooms are so small, and the lighting/sound technology so bulky that there's no space to run services along the wall. They are instead routed across the ceiling and left exposed.

Secondly, much of the RADA building is completely enclosed. This applies to the workshops and theatres in particular. Before the refurbishment, there was no mechanical ventilation, making some areas very uncomfortable to work in. Better ventilation and cooling were major client concerns.

The lack of windows did have the advantage of reducing solar gains, but in a theatre there are other considerations: "Solar gain problems don't really apply to this building, as so much of it is enclosed. But there are heavy lighting gains because of the theatrical lights. The biggest gain is over 120 kW. So the main problem is therefore ventilation." Natural ventilation wasn't a practicable solution for the RADA building. "The whole design team including the client were keen to adopt an environmentally sound solution, but a variety of constraints and objectives meant that it wouldn't really have made any difference as so much of the building is enclosed, and not much can get in the way of natural ventilation. It's mainly corridors and staircases which are open, rather than the occupied spaces. So natural ventilation is not going to make a great deal of difference to the overall energy use of the place," explains Wood.

They used to show productions in the theatre with the full lighting, and no ventilation at all

The plantroom containing the air handling unit is situated on the top floor of the building, two 220 kW, R407c chillers are situated within the plantroom on a mezzanine level.

Internal design conditions were set at 22°C for the summer and 21°C in winter, although there are allowances for temperatures to rise in the theatres for short periods when lighting requirements are at their peak.

Fan coils for heating and cooling are also present in each classroom or office area. Two 320 kW gas-fired boilers are installed to provide the heating requirements throughout the building.

With the average outside temperature in London being in the region of 12°C, and most performances being in the evening, 'free cooling' is often sufficient for the building requirements. Wood adds that in the case of the RADA building, the benefits would be minimal.

The third main challenge was noise pollution, as a number of the classrooms and other areas open out onto the street and central courtyard. And in the case of this building, noise pollution works both ways. "The other problem to overcome is that the building next door is accommodation for nurses. This means the neighbours are sleeping during the day as well as the night. The RADA students could be singing, shouting, maybe even screaming in their rehearsals and classes. So we had to keep noise in, as well as out." On the exterior of the building, the traditional sash windows have been retained in keeping with the building's original appearance. Double glazed secondary glazing has then been installed on the inside. The windows can be opened from inside, but this is intended to be for cleaning, not ventilation purposes.

Particular attention had to be paid to to the acoustic insulation for the theatres and control rooms as well as the sound studio suite and recording control rooms, which required additional sound insulation.

Finally, the building's multi-functionality posed a real challenge for service design. The building is used not only as a school, but also includes workshops for teaching woodwork and welding; as well as the theatres.

Also, RPP had to take into account the building's change in status. "Before the refurbishment, only those in the school and private guests were invited to the building. But because the refurb was partly paid for with money from the National Lottery, RADA had to agree to invite members of the public to performances," says Wood. "This meant of course that we had to comply with rules on public safety, and regulations on lighting, temperatures and so on." Wood adds that when he first saw the building, he found a couple of fans in the basement, which no one had dared turn on for fear that they would 'blow' the whole system. "They used to show productions in the theatre with the full lighting, and no ventilation at all. They could do that because they didn't have to comply with regulations as it was purely private." Naturally, as a school RADA also has to look to its budgets, so costs had to be minimised, both in terms of capital outlay and long-term running costs. This is one of the reasons why RPP did not recommend full air conditioning, which would have been a more expensive option all round – although the lack of space also dictated against this.

Conclusions

The client in this case did have the option of moving to new premises, but elected to retain its central London location. This is understandable, given the Academy's purpose of training students for work in theatre, film and television. However, this did leave the engineers with limited space in which to design the services. Anyone seeing the roof spaces and ceiling clearances available, would be surprised to learn that RPP did not resort to bespoke equipment, specially manufactured to fit the space.

The building has been occupied for less than a year, so it's not possible to give feedback on the efficacy of its cooling and heating. Also, as Martin Wood points out, testing the overall performance of the building would be difficult due to the many uses of its different areas.

That said, the building felt comfortable, draught-free and there was a relatively stable temperature from one area to the next. In the large Jerwood Vanbrugh theatre, with lights on, the space was well cooled. Considering this wasn't previously ventilated at all, it can only be an improvement.

None of the windows in the building had been opened on the day of our visit, which indicates that occupants were happy with mechanical ventilation. Whether this continues to the height of a London summer is another question.

A particularly challenging aspect of the work on RADA is that none of the services design was repeatable. Each space has a different purpose. The theatres are all different sizes, and completely different in layout.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Credits

Client Royal Academy of Dramatic Art Project manager Buro Four Project Services Construction manager Laing Architect Avery Associates Building services consulting engineer Roger Preston & Partners Acoustic consultant Paul Gillieron Acoustic Design Theatre systems Theatre Projects Consultants Structural engineer Ove Arup & Partners Quantity surveyor Davis Langdon & Everest M&E contractor Rosser & Russell Building Services

No comments yet