While the DETR prepares to release guidelines on flood defence, insurance companies are sorting through claim-forms and planning future policy. Their costs are still being counted but estimates are already huge – the Association of British Insurers says claims will be between £400–500 million.

As a result, the Halifax, Britain's biggest home-insurer, has said it will not spread flood-costs among its 1.6 million policy-holders. This is good news for some, but for the 12 000 claimants who suffered last November, premiums could rise by as much as £1000.

This seems increasingly likely when a consensus view is growing that the storms were not freak weather events, but the effect of global warming. Even back in 1996, the DETR's global atmosphere division was predicting a global rise in temperature of 0.20C per decade and sea level rise of 50 mm per decade. The national picture is set to become clearer this year, when the Hadley Centre publishes the first computer predictions showing specific effects of climate change on the scale of the UK.

Even without that, experts warn that severe weather conditions in Britain will become more common: annual precipitation will be 5% higher by 2020 and 10% higher by 2050. The frequency of gales will rise by 30% by 2050. All this puts the onus on developers and local authorities to reduce the threat of flood damage.

Sadly, the places where Britain's flood defences worked went largely unnoticed as the media focused on submerged high streets. Yet only 8500 properties of 1.8 million at risk across Britain were badly affected. "Miraculously we didn't have too many breaches over the last two months, we got by by the skin of our teeth," said Dr Geoff Mance, the Environment Agency's Director of Water Management.

This was especially true in York. At the height of the crisis the river Ouse rose an unprecedented 17ft 8in above its normal level pushing defences to the absolute limit – some flood walls had a margin of less than two inches. But in total only 350 houses were damaged compared to 900 in the less serious flooding of 1982.

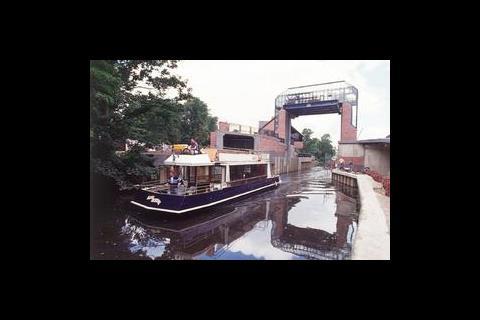

One reason for this success was York's flood defences. The Environment Agency spent £8 million on measures that included concrete retaining walls, flood plains and river gates. The bulk of the project was simple civil engineering, but there were also substantial building projects that had to be tackled. Flood gates were erected in North Street and a pumping station at Holgate Beck. The two technologies used in these projects came together in 1986 with the building of the £3.34 million Foss Barrier.

This huge facility is a moveable barrier system, a 6.5 tonne 'turn and lift' gate that is lowered to isolate the Foss from the Ouse. It will keep the level of the Foss at 6.5 m (above ordinance datum) and stop water from the Ouse surging into the Foss and then through York city centre. When closed the gate prevents water flowing naturally from the Foss into the Ouse.

“House builders cannot go on acting like ostriches, making profits with their heads in the sand. The Government shouldn’t stand for it”

Dr Geoff Mance

Eight pumps, each rated at 236 kW ensure water can still be moved. These shift flow from the Foss around the closed barrier and then into the Ouse. Each pump can move water at 3 tonnes/s (or 32 m3/s). During November 2000 the barrier was put to its greatest test yet – a record seventeen days of successful operation.

The Environment Agency estimates that without the £3.34 million barrier there would have been £10 million-worth of damage.

With spending in Yorkshire proving that the devastation of flooding can be limited, the Environment Agency is arguing that there must now be considerable funding for other projects. Dr. Geoff Mance told the House of Commons Agriculture Select Committee that £100 million is required each year to make-up for the years of under-investment. In some places this has already begun. In Maidenhead an £84 million, 11.6 km relief channel is nearly finished.

The debate over building on flood plains is one that has been difficult to settle. In the last twenty years 400 000 properties have been built in risky areas, 28 000 of those since 1996. It is a practice that looks set to continue, 350 000 out of four million proposed new homes are to be built on flood-plains.

The Government has been fairly cool about this. Speaking in December, the Countryside Minister Elliot Morley said there were no plans to stop the developments. But there is formidable pressure from the Environment Agency, which is hoping the Government will grade flood-plains in order of risk.

The DETR is to set out an agenda in February, but already the Association of British Insurers has made several recommendations in its September 2000 flood report. It says one reason structures are vulnerable is that there is a lack of knowledge – 50% of homeowners in flood-risk areas are unaware of their situation.

The Environment Agency's strategy is to reverse this trend. In December they went on-line with an impressive set of maps indicating worst-case flood scenarios. Based on historical flood records and geographical models these maps show exactly how local areas might suffer. Initially the website was too successful to cope with demand – 10 000 hits in the first three hours made the server shutdown.

The ABI report also outlines how buildings might be made less vulnerable: "Buildings could be designed or modified, often at little or no extra expense, to make them more resilient to flood." The report suggests raising floor levels, keeping kitchen appliances off the ground and setting plasterboard sheets horizontally instead of vertically. Electrics should also be kept high — underfloor wiring should be avoided and power sockets fixed half-way up walls.

Further reading

Surveying flood damage to domestic dwellings: The present state of knowledge. RICS Research Foundation, 11/2000. Wetmore F, Retrofitting for flood protection: a status report. In Natural Disaster Reduction, 1997. B.Govind Rao and Sharm A K, Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering for Protection from Natural Disasters, 1980. The BRE has a number of reports on drying out buildings and dealing with flood damage. The most useful documents are the Good Repair Guides.Source

Building Sustainable Design