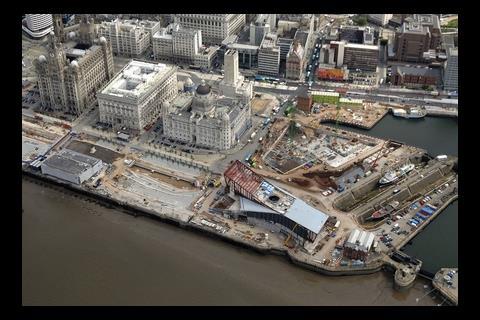

There is just one thing about 3XN’s Museum of Liverpool on which everyone agrees: it will offer fabulous views of the Mersey. Thomas Lane looks at the construction challenges behind the city’s most controversial new structure.

The new Museum of Liverpool is turning out to be a love it or loathe it kind of building. The fans like its long, low, sleek lines, reminiscent of its Danish architect 3XN’s Copenhagen Opera House. The detractors moan that this piece of streamlined Scandinavia has nothing in common with its upright looking neighbours, the Edwardian Three Graces next door. But now that the structure is up and the cladding is going on, it’s definitely here to stay.

Whatever locals think, it’s an undeniably arresting building. Just three storeys high, the top floor is a clearly defined, long box, cantilevered over the floors below at either end. For further emphasis, the box slopes down from the ends towards the middle. Two large, fully-glazed galleries at each end

of the box offer stunning views over the Mersey towards Birkenhead on the opposite bank and the Three Graces in the other direction. “We wanted to have a lens on the river rather than a museum in a big black box,” says Sharon Granville, the museum’s executive director. Visitors will be able to access the two main galleries via two large ramps on either side of the building as well as at ground-floor level.

Building this unusual structure was far from straightforward. The construction team had to devise innovative solutions for the foundations and the frame, and these, in turn, affected how the cladding and internal elements had to be built.

Underground

One reason the foundations required a special solution was that the building sits right over the Mersey Railway Tunnel on top of a reclaimed dock. “We normally would have gone for a piled solution, but because of the tunnel we came up with a cellular raft foundation,” says David Taylor, Buro Happold’s structural engineer. “We also had to maintain the existing dock walls for archaeological reasons.”

Effectively, the raft foundation comprises a giant 100m-long and 49m-wide beam that bridges the tunnel and functions like an I-beam, with an upper and lower flange separated by a web. The foundation slab has a 400mm-thick lower flange with a 300m-deep upper flange, and the two are separated by a series of 3.5m-high cross walls.

This design presented the contractor, a joint venture with Galliford Try and Danish contractor Pihl, with several challenges. For a start it had to ensure the loads over the tunnel remained constant, so the soil had to be removed carefully and replaced by concrete of the same weight. “We had to construct symmetrically to ensure we loaded the tunnel evenly,” explains Christian Lundhus, project manager for Pihl.

Another issue was the complex arrangement of cross walls within the foundation. The top-floor box is a parallelogram rather than a simple rectangle, and as the cross walls replicate the structure above, they are not square either. This meant the formwork had to be specially made where it met at the corners.

On the surface

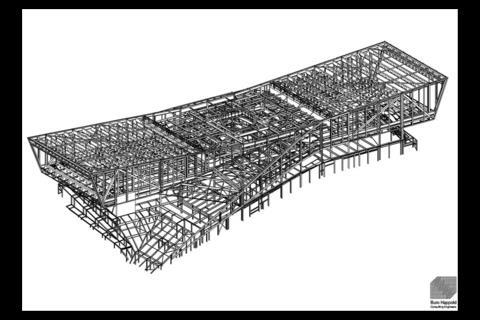

The huge, cantilevered galleries on the top floor span up to 27m. The box cantilevers 9m over the lower part of the building on the north end and 5m on the south end.

As the top floor has no internal columns, building it required a complex steel frame that weighed 2,100 tonnes – its size meant it had to be split into three sections to accommodate thermal movement. The frame needed temporary propping while under construction, which proved awkward.

We would have gone for a piled solution, but because of the tunnel we came up with a cellular raft foundation. We also had to maintain the existing dock walls for archaeological reasons.

David Taylor, Buro Happold

“It was tricky on the north side, because one of the support towers was located right where the canal is,” says Lundhus.

The solution was to build a bridge over the canal to support the temporary prop. This rests on the new foundation at one end, but piles had to be put in to support the other. With the props in place, the steel could be erected and the concrete floor slabs cast. These were allowed to cure for 28 days before the props were removed to allow the building to settle to its natural position. When the props were removed, the building dropped 10mm at each end and Lundhus could then start on the facade and the roof.

Inside

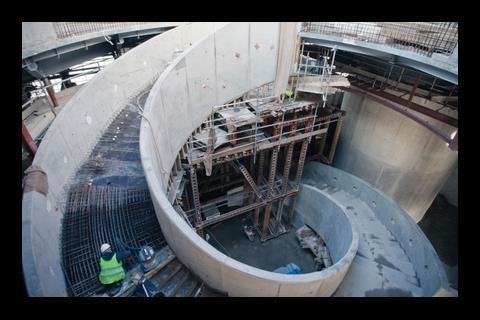

Internally, the centre of the building features a large spiral staircase that is only supported at its base and the intermediate floors. It functions as a kind of curled up, H-section beam and is constructed from insitu concrete. “Because the staircase is such a special structure there is no standard formwork so it had to be specially made,” Lundhus says.

The whole structure is very complex, he adds, with just about enough room to fit a crane in the centre of the support structure. When the staircase is completed, the concrete, again, has to be allowed to cure for a nail-biting 28 days before the supports can be removed. “Now we can see it is achievable, it is a relief,” Lundhus says.

Outside

Externally the cladding is progressing well. This was originally to be travertine marble but is now Jura limestone. “It was felt that Jura limestone would be a better long-term solution in terms of weathering and standing up to the elements, as the building is by the Mersey and the sea,” explains Kieran Brennan, Galliford Try’s commercial director.

He says the facade was also a key area for value engineering the building. It was originally £4.1m over budget, but as Pihl was also a cladding contractor, it helped drive down costs. The facade was originally going to be made from precast concrete sections, but it was changed to a rainscreen design. “It saved money,” says Brennan. “There were buildability issues with the precast concrete, plus the new design helped with the programme.”

The limestone is delivered to site fitted into a galvanised steel frame, which is simply bolted on to fixing points. Brennan says these steel-framed panels are lighter and easier to replace if damaged during construction.

The rest

The main challenge remaining is logistics. Lundhus says the interior is relatively straightforward but co-ordinating all the external works is going to be complicated. “It’s my biggest worry as there is a lot to be done,” he says. “We don’t allow two subcontractors to work in one space at one time, so I need to work out the programme for the drains, cladding and the glazing. People will have to jump around a bit, but it means it will be safe.”

Galliford Try and Pihl hand over the building in the middle of next year for a £15m fit-out and the building should be ready to welcome the public a year or so later. By then it will have had enough time to get used to the building and may be ready to welcome it as a part of a revitalised Liverpool.

Postscript

Photographs by Peter Corcoran

Original print headline "Museum of Liverpool: A lens on liverpool"

No comments yet