Billionaire businessman Roger de Haan is reversing his Kent home town’s gentle decline into dereliction. Martin Spring found what he’s giving back – and if you turn up at his arts Triennale next summer, you can too …

Three years ago, Roger de Haan sold his family firm. He was 56 years old so his first instinct was to retire, but he decided to become a property developer instead.

An everyday story of small-time business folk, perhaps. Except that the firm was Saga and the sum de Haan and his family reaped from the sale was £1.35bn before tax.

Saga was set up by de Haan’s father in Folkestone in the fifties to provide holidays and financial services to the over-50s. It is now worth £6.8bn, employs 2,500 people and remains based in the Kent seaside town.

Not exactly a developer red in tooth and claw, de Haan takes an enlightened approach, informed by his experience at Saga. “My father and I strongly believed we needed to make Folkestone a successful place to live and run our business in,” he says. “We thought that the more successful Folkestone was as a town to live in, the more successful our business would be. So when I sold Saga, I decided to focus on regenerating the town.”

For a man ranked 78th on the Sunday Times Rich List, with a reputation for extraordinary drive, de Haan comes across as modest and unassuming in manner. He granted Building a rare interview at his office in an early Victorian house in a western suburb of Folkestone, a few hundred yards from Saga’s headquarters. Although small and unprepossessing from the street, the building’s interior reveals another de Haan passion – contemporary architecture.

Picking one’s way through the plastered front rooms, the visitor notices there is no back wall. Instead, a frameless glass screen opens onto a wide shingle beach a few steps away and the English Channel beyond that.

The house conversion was designed by local architect Cheney Thorpe & Morrison. For more ambitious schemes, de Haan has brought in such big-league architects as Foster + Partners, Pringle Richards Sharratt and Alison Brooks Architects. He also regularly works with cost consultant Davis Langdon and town planner Montagu Evans.

To regenerate Folkestone, de Haan homed in on the old town centre next to the harbour, which he says was “extremely rundown and fast turning into a slum” in 2004. He is also working to revive the harbour itself, from where the ferry service to France ran, before it was killed off by the Channel Tunnel in 1994.

De Haan takes a philanthropic approach to urban regeneration – more like a charitable organisation such as the National Trust than a private property developer. “Our first idea was to create an artists’ quarter and later we developed this into the Creative Quarter,” he says. “This entails buying rundown properties in the area, renovating them and leasing them at affordable rents to people in the creative industries.”

The big risk here is what de Haan calls “the Hoxton effect”, referring to the district to the north of the City of London, which was colonised by artists, designers and film-makers. “Often, artists are used to help regenerate an area and once it’s regenerated they’re forced out because rents are too high.”

De Haan’s solution is to retain the freehold of the properties and rent them directly to end users on 125-year leases and peppercorn rents. This is where his personal fortune plays its part. He is bankrolling two charitable trusts that plough the revenue generated by refurbished properties back into the regeneration pot.

The first is the Roger de Haan Charitable Trust, which buys properties, renovates them and retains the freehold. The second is the Creative Foundation, which has representatives from Canterbury Christ Church University and the South East England Development Agency as fellow trustees. The Creative Foundation manages the properties and stages arts festivals and other cultural events in the area. Its latest initiative is to launch the Folkestone Triennial, which bills itself as “a major three yearly exhibition in the public realm”.

The Creative Foundation grew out of Folkestone’s long-standing Metropole Arts Trust, which first called on de Haan and Saga’s support in the late nineties, when it was losing its grants and financial support. “So it wasn’t a great jump for me to continue and concentrate on supporting the town and its charities and institutions,” he says. It was also the connection with Metropole that led to the area’s revival being aimed at the creative industries.

Now, three years into the regeneration project, about £42m has been sunk into acquiring 65 mostly small-scale, properties in the Creative Quarter and refurbishing them. Many have been converted and let to a bubbling new community of fashion shops, hairdressing salons, small restaurants and a florist-cum-coffee-shop. A £4m performing arts centre designed by Alison Brooks has just started construction and will combine a flexible auditorium and business start-up units for creative companies. The next stage will be to unravel a tortuous one-way road system by working with the county and district councils.

So far, so good. “But these efforts would not be fully successful,” warns de Haan, “unless we looked at some of the broader issues. One of these is education.

“When we started this project, Folkestone had one of the worst performing secondary schools. This school served most of the people from the east end of town – the slum area around the harbour – so we built a city academy, which I sponsored.” The new academy, built to a highly original design by Foster + Partners, opened last week.

Often, artists are used to help regenerate an area and once it’s regenerated they’re forced out because rents are too high

Roger de Haan

“The other thing we did was to set up a university campus here.” This is an outpost of Canterbury Christ Church University, based 18 miles away, and London’s Greenwich University – but focused on the arts and media. The first phase of the campus – a conversion by Pringle Richards Sharratt of a derelict glassworks in the heart of the Creative Quarter – opened to 500 students last week. Next door, an adult education centre for Kent council is being converted out of a four-storey building.

“With the city academy, adult education centre and university, we think education in the town will be transformed,” says de Haan. “For the first time, our brightest kids will be able to stay in the town to do their degrees. Until now, we’ve had a brain drain.”

The campus project has not been without its headaches, however. “Two-thirds of the way through, the universities we were working with announced that the campus we were planning was only half the size it needed to be. It would now have to cater for many more students than originally planned,” he says.

“Then I heard the harbour was for sale and I bought it for the university campus. That led to the purchase of the rest of the seafront, which had a broken-down old funfair that closed a few years ago.”

Redeveloping the 16 ha seafront site is in quite a different league from the small-scale refurbishments of the Creative Quarter. “I bought it in a moment of madness to secure it for the university. Sometimes I wake up wondering what the hell I’ve done. I had a great battle with the adjoining landowner to acquire part of the site, but eventually managed that last year.”

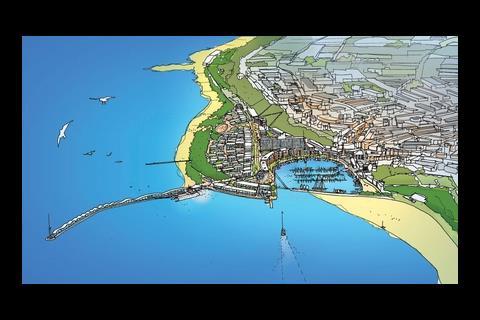

An ambitious masterplan has been drawn up by Foster + Partners for housing and a marina, as well as the second phase of the university campus. As a major commercial development, the seafront demands a more aggressive procurement strategy than a charitable trust can manage. “I’m beginning to meet builders and developers I could work with. I went to Eastbourne the other day to meet the team doing the marina there.”

Here, property price inflation will be encouraged, to make the scheme viable for commercial developers. To attract home buyers, de Haan puts his faith in the proposed high-speed commuter rail service to London, which will come on stream in 2009 if approved.

Despite the hard commercial decisions demanded by the seafront development, de Haan is determined to realise the architectural ambitions of Foster’s masterplan. “Part of my mission is to ensure that Foster’s additions to the public realm are actually delivered and that it becomes a place that people want to live in and visit.

“Over the past 60 years, Folkestone has become disconnected from the sea and Foster has taken great care to ensure that the boulevards will link the seashore to the town. I want to do my best to make sure that that is what gets built.”

The final plank in de Haan’s arts-led regeneration strategy is the Folkestone Triennale, which will take place next June. “We’ve invited some of the leading contemporary artists of the world. The idea is to produce works that are connected to Folkestone and reflect something of the place, its culture and its people.”

De Haan is hoping for something more than a few wan sculptures on pedestals. “It’s very much an open brief. Some of them will raise eyebrows and some are mobile works, which will be that much more engaging.”

The plan is for many of the public works to remain in place after the exhibition finishes. Two more triennials in four and seven years’ time will add to the collection.

“People will be attracted, not just to the shows, but between the shows. It’s got to be taken with all these other elements of our regeneration plans to go towards this concept of place-making.”

Three years into the six-year regeneration project of the Creative Quarter and one-third of the way through the building renovation programme, some 150 jobs have been created in retail alone. The Creative Foundation reckons it is on track to meet its target of 1,000 new jobs by 2010, half of which will be generated by the three new arts and education establishments.

All in all, de Haan’s success in urban regeneration can be attributed to his active engagement with the community and its institutions as much as to the fortune he is investing in it. Kent and Shepway councils both testified on their close working relationship with de Haan.

Ray Johnson, chairman of the local chamber of commerce, says: “With his financial ability, Roger could have built a massive great tower block and just walked away. But he is meticulous at getting things done well, so he has put time into consulting the local community. I can’t think of anyone who has knocked his plans in principle. His development projects really are for the people, not for Roger.”

9 Readers' comments