Supply-only deals don’t normally go to adjudication but here’s one that did largely because neither side had a clue what the terms of the contract said

Pro-Duct (Fife) design, manufacture and install M&E ductwork. Recently it bought a lot of ductwork from key supplier, Specialist Insulation. It was for the project at Edgbaston Cricket Ground to keep the West Indies on their toes this summer. Notice at once that this is a supply-only contract. We all know that supply-only deals are not construction contracts at all, and so adjudicating a dispute is a “no-go”. Well, actually, this one did go to adjudication and, yes, it was a supply-only, and the adjudicator ordered Pro-Duct to pay up £86k to its supply-only supplier. Pro-Duct protested loudly. How come a supply-only deal went to adjudication?

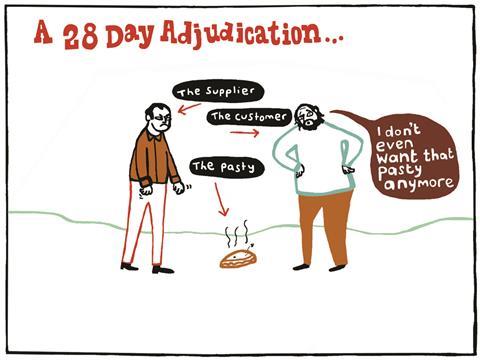

Easy really. It’s wide open for almost anyone to enter into a contract for almost anything and agree in their contract that a dispute can go to 28-day adjudication, just as though it was a construction contract. So, if the duct maker was also the installer, that would be a construction contract, and parliament says that “supply and fix” deals automatically include 28-day adjudication.

Anyone can enter into a contract and agree that disputes go to 28-day adjudication. If I supplied pasties, ping-pong balls or bagpipes I would want 28-day adjudication, like builders have

If the duct maker supplies ducts, it needs what we call an express term in the supply contract to bring in adjudication. And I have no doubt that if I was a supplier of pasties, ping-pong balls or bagpipes, I would want 28-day adjudication just like builders have. Give me a 28-day punt rather than a 28-month litigation trawl and 28-month bill.

Now then, in real life trading, most folk work on auto-pilot. Think about it in your firm. Every day you use pretty well the same pro-forma to bash out your bids. The pro-forma says “estimate” or “quotation” or some similar term. The form probably has small print on the back or signposts to some other form of contractual nonsense. If I asked you what the small print said, you wouldn’t have a clue.

The buyer at the other end is really only interested in the price and a discount. He doesn’t read your small print, either. His order form to you also contains small print and the buyer can’t recall what that says. So the order goes off and the duct supplier supplies his metal bits and sends his invoice. That’s more or less what I guess happened between Pro-Duct Fife and Specialist Insulation.

Then, of course, they fell out. Specialist Insulation was annoyed about money outstanding. Their lawyers looked to see what the rules are in the contract for managing disputes. As usual, the quotation said one thing and the order said another. You would expect Specialist Insulation to want to rely on their quotation rules and terms, wouldn’t you? They will have naturally been swerved to favour Specialist Insulation.

You spend most of your life trying to show that your clients’ terms apply. But here it’s the opposite

No, not this time. Instead they fancied relying on the buyer’s rules and terms printed on their order. Why? Because Pro-Duct’s small print contained a 28-day adjudication clause. Pro-Duct pulled a face. No, said Pro-Duct, our terms don’t apply, yours do. No, said Specialist Insulation, our terms don’t apply, yours do. That will bring a smile to all

those who have adjudicated disputes. You spend most of your life trying to show that your clients’ terms apply. But here it’s the opposite.

The adjudicator in this case was faced with having to fathom whether to go with Pro-Duct’s order with 28-day adjudication for “supply and fix” that was not “fix” at all, or go with Specialist Insulation’s plain supply-only terms which would deprive him of his job as adjudicator. He plumped for Pro-Duct’s terms and eventually ordered them to pay up the £86k. But they refused to obey the terms on their own order.

So, the Scottish Court ended up having to get to grips with all this and the Scottish judge agreed with the outcome of previous similar cases dealt with by English judges - an objective approach asks, of the words and quotations, orders and context, what do the documents convey as the common intentions of the parties?

In short, the words in his view did not intend 28-day construction contract adjudication to apply to this supply-only contract. So Pro-Duct need not obey the adjudicator. Instead, their supplier will have to take them to court. And in my humble view, litigation costs for an £86k dispute may prove that they would have been better off with 28-day adjudication.

Tony Bingham is a barrister and arbitrator at 3 Paper Buildings, Temple

No comments yet