With vertical glazing or cladding, solar reflection is usually only a problem if there are large areas of glass or if the sun is low in the sky. Reflection of low angle sun is unlikely to be such a problem for motorists as they will be expecting the glare from the sun as they drive around. Similarly, facades that slope forward, so that the top of the building forms an effective overhang, are unlikely to cause difficulties.

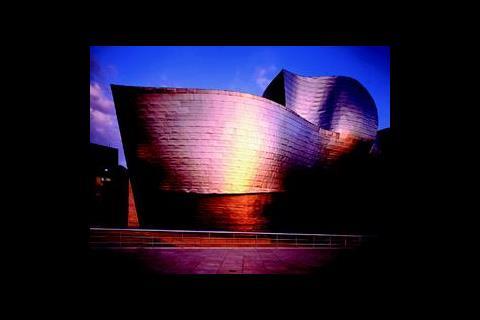

A facade that slopes back from the vertical is likely to be more of a problem, as it can reflect high angle sunlight along the ground. Where the reflecting surface is close to the vertical, it will reflect sunlight back along the ground, so areas to the south of the building will be more at risk. Where the reflecting surface is nearer to the horizontal (figure 1) it will reflect sunlight onwards, but at a lower angle. In this case, areas to the north of the building could experience reflected sun.

BRE have developed a method1 to calculate the times of day and year when sunlight can be reflected from a facade (sloping or vertical) towards a point near it. This can be used to assess the likelihood of glare occurring.

Large areas of reflecting material are more likely to cause problems than small areas. With a small area of glazing or shiny cladding, the likelihood of solar reflection to a particular point decreases. Also, motorists or pedestrians only have to move a short way for the reflection to stop.

Glare

The Commission Internationale d'Eclairage (CIE) defines two types of glare2. Disability glare occurs when a bright source of light impairs the vision of other objects. A typical example is when an oncoming vehicle at night dazzles a driver and makes it impossible to see the road.

Discomfort glare, as its name implies, causes visual discomfort without necessarily affecting the ability to see. An example could be over bright lighting in a workplace.

Discomfort glare can cause distraction, and be unpleasant if people are working for a long period

Outdoors, disability glare is easily the more serious problem, as it can affect motorists' ability to drive safely. For this reason, guidance on limiting solar reflection in Australia3,4 has concentrated on disability glare.

Cochran4 has developed a technique to assess disability glare from reflective facades. Disability glare occurs when a bright source creates a veiling luminance in the eye. This looks like a bright veil over the visual field, making it harder to see everything else. The veiling luminance is proportional to the illuminance at the eye due to the light source, so it depends on the specular reflectance of the glazing or cladding.

The veiling luminance is also proportional to the inverse square of the angle between the glare source and the observer's line of sight. This is important; it means that glare sources off to one side, or above the observer, are less likely to cause disability glare.

Usually, glare sources at more than 25° to the line of sight can be discounted5. It is necessary to consider what sight of the building motorists and pedestrians will have. If, for example motorists are directly facing a reflecting facade at road junctions or pedestrian crossings, the risk of reflected disability glare could be important.

The impact of the veiling luminances depends on the overall brightness of the lit scene. A veiling luminance at night (caused by car headlights for example) will have a bigger impact on visibility compared with the same veiling luminance during the day, when objects are brighter and easier to see.

Discomfort glare can cause distraction, and may be unpleasant if people are working for a long period, but it does not affect the ability to see. Outdoors, on a bright sunny day, there can be many sources of discomfort glare. Windows, street furniture, building cladding and vehicles can all give reflections which may be uncomfortably bright but are acceptable. Discomfort glare can be more of a problem if workers (perhaps in buildings or kiosks opposite) have to spend a large proportion of the day facing the building, and the geometry is such that the sun can be reflected towards them.

Downloads

Figure 1

Other, Size 0 kb

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Reference

References

1Littlefair, P J, 'Solar dazzle reflected from sloping glazed facades' BRE Information Paper IP22/89, CRC, Garston, 1989. 2'International Lighting Vocabulary' CIE Publication 17/4. Commission Internationale d'Eclairage, Vienna, 1987. 3Hassall, D N H, 'Rogue solar reflections' University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, 1986. 4Cochran, L, 'Solar glare events from glazed curtain walls' Proc ANZSES conference, Brisbane, 1988. 5Schreuder, D A, 'The visual cut off angle of vehicle windscreens' Lighting Research and Technology, 17 (4) 192-193, 1985.

Postscript

Dr Paul Littlefair is Associate Director of BRE's Environmental Engineering Centre. For information about solar dazzle or solar gains call: 01923 664874 or e-mail: littlefairp@bre.co.uk