This year’s striking schemes include AL_A’s imaginative extension to the V&A museum, Foster + Partners’ superlatively sustainable Bloomberg HQ, and Herzog & de Meuron’s triumph over chaos in Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie. Meanwhile, Cambridge university made a strong and surprising move to tackle housing undersupply, while uncertainty haunts the towers of the City of London.

V&A extension

London, UK

Architect: AL_A

Contractor: Wates Construction

2016 offered up two major cultural building openings in the capital, the Tate Modern Extension and the Design Museum. This year only really offered one, and it comes in the shape of Amanda Levete’s striking and eagerly anticipated extension to south Kensington’s world-famous V&A museum. This is not so much an extension as a reimagining, because Levete’s ambitious interventions repackage a significant portion of the museum’s existing historic fabric as part of the process of providing new accommodation.

The removal of the boilers from the eponymous yard that once housed them for almost a century is the catalyst for the scheme, and in its place Levete has created a generous new public courtyard fully connected to the public realm of adjacent Exhibition Road through the restoration of Aston Webb’s elegant screen.

Internal spaces are marked by a theatrically dramatic stepped descent into new subterranean spaces. Chief among these is the spectacular Sainsbury Gallery, a gigantic sunken vault whose trussed, serrated ceiling swerves across a cavernous 38m span and is lit by shafts of daylight that pour downwards from a handful of overhead portals.

The courtyard cafe sets the solitary discordant note, its abstract form and metal skin jarring with the ornamental Edwardiana surrounding it.

The scheme finally puts to bed Daniel Libskind’s aborted and hugely controversial Spiral proposals for the same site, which were finally abandoned in 2004.

Its position as the only major London cultural project on this list also emphasises the extent to which the sector has contracted since the heady days of the 2000s and early 2010s.

Bloomberg

London, UK

Architect: Foster + Partners

Contractor: Sir Robert McAlpine

Media billionaire Michael Bloomberg did not hold back when he famously condemned the outcome of the EU referendum as being “the single stupidest thing a country has ever done”, after investing an estimated £1bn building the headquarters of his media, software and data empire in the UK.

Eleven years ago this site was set to host a horrendous 22-storey glass pustule nicknamed “Darth Vader’s helmet”, which was then mercifully lanced by the credit crunch. While one half of the culpable design team – in the form of Jean Nouvel – shuffled off the stage, new site owner Bloomberg retained Foster + Partners to draw up a replacement scheme. The result is the vast corporate temple that opened this autumn, covering 3.2 acres in one of the most dense and historic parts of the City.

Cast from thousands of tonnes of bronze and encased in a hulking sandstone shell that allegedly emptied out a Derbyshire quarry, the new headquarters offers over a million square feet of some of the highest-grade office space to be found anywhere in the world. Highlights include a curving, cave-like foyer and a stunning vortex atrium through which one of Foster’s trademark ramps unfurls.

A host of superlative sustainability credentials include an innovative aluminium “petal” ceiling system that regulates lighting and acoustics and embedded breathable “gills” on exterior walls. The BREEAM score these features earned the development awarded it the title of “most sustainable office building in the world”. But what is perhaps most surprising about the Bloomberg building are three words that sadly in recent years seem less applicable to office building in the City of London: responsibility, sensitivity and context. Bloomberg himself deliberately eschewed the high-rise template allowed by local planning guidelines and instead sought a building that in its scale and materiality mimicked the historic character of London. Ironically, his efforts might suggest that the City needs as much protection from its planners as it might or might not do from Brexit.

City of London towers

London, UK

Various architects and contractors

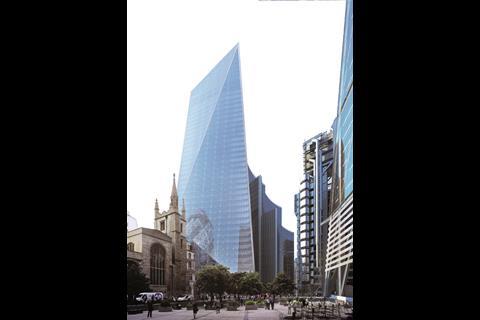

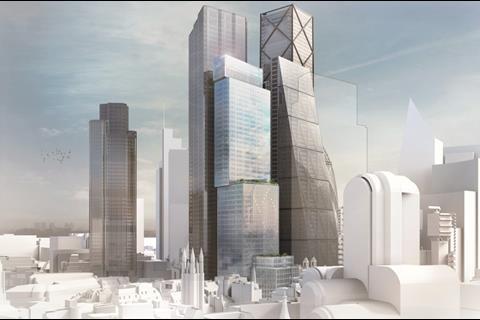

Eighteen months after the landmark EU referendum, no one is yet sure quite what its long-term impact on London’s commercial property market will be. One of the biggest bellwethers for change remains the development of tall buildings and major projects in the City of London, which for now is still Europe’s financial capital. In attempting to measure even just the short-term impact since the referendum, that picture is inconclusive.

On the plus side, a whole flurry of major projects that might have potentially been threatened by the decision to leave the EU are storming ahead. Among these are 22 Bishopsgate, the Scalpel (52 Lime Street) and 100 Bishopsgate, as well as a host of planning permissions for towers such as 6-8 Bishopsgate and 1 Leadenhall. On top of this, big banks including Wells Fargo, Deutsche Bank and even a Brexit-disparaging Goldman Sachs are ploughing ahead with the construction of their European headquarters in the City.

But on the other side, schemes such as 2-3 Finsbury Avenue and 40 Leadenhall are still on hold, 1 Finsbury Avenue has been significantly scaled back, and there has been a marked shift away from speculative development and towards pre-lets. Developer Peter Rogers has even bemoaned Brexit as the reason he currently has no pre-lets on his 22 Bishopsgate tower.

Office leasing levels released last month show just how difficult it is to glean any consistency about Brexit’s impact: while leasing is said to have hit a 10-year low in the City, demand in the West End is the highest for over a decade. Ultimately, Brexit’s long-term impact on London’s commercial development market will come down to one thing: jobs. If there is the jobs exodus that some fear, then demand will obviously crash. The Bank of England has already predicted up to 75,000 job losses in the UK’s financial sector as a result of Brexit. But considering that London employs close to a million people in this sector – compared with its next competitor Frankfurt’s 75,000 – then it is possible that demand for City towers will be as much a feature in the near future as it has been in 2017.

Eddington

Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK

Various architects and contractors

As Britain’s housing crisis endures, building on greenbelt land has become the political and societal hot potato that won’t go away. Throughout 2017 developers and increasingly planners argued that building on brownfield land was not enough and demanded a loosening of national planning rules protecting the land around cities.

It was seen as a missed opportunity when Hammond held back in last month’s Budget from taking steps towards freeing up greenbelt land for development. Such a move would have been intensely controversial, as there is no consensus on the issue – with cynics claiming developers are shirking from brownfield land only because it is generally trickier and costlier and to redevelop. But if greenbelt land is to be developed, then Eddington might be a model for the future.

The £1bn North West Cambridge development is situated on greenbelt land around the edge of the city and is a reflection of the rapid pace with which Cambridge is expanding. It aims to provide 3,000 private and affordable homes for Cambridge university staff and non-university residents alike. Its first phase, Eddington, opened in the autumn and offers a masterclass in design quality, public space and community development.

Various architects have been recruited to the scheme, and yet each building conforms to a subtle palette of geometries and materials that strikes just the right balance between consistency and diversity. Generous civic amenities have been included, such as a school, a supermarket, a town square and eventually, a hotel, each one revealing the developer’s core determination to anchor the development around a living community that extends far beyond the site’s boundaries.

But it is arguably the identity of the client rather than the greenbelt location that is most significant here. After all, if the green belt is to be developed, it is no revelation that high-quality development is the best way to do it. But the fact that the developer is the University of Cambridge itself proves that exceptional design is attainable through any development model, and it also broadens the pool of potential protagonists capable of addressing the housing crisis.

Elbphilharmonie

Hamburg, Germany

Architect: Herzog & de Meuron

Contractor: Adamanta and Hochtief Solutions

It is testament to the strength of German pride and the durability of its overseas brand that a host of disastrously mismanaged national projects have consistently failed to dent either national self-confidence or Germany’s international reputation for efficiency and organisation.

Were the horrendous catalogue of errors, delays and overspends that afflicted projects including Berlin’s Brandenburg airport and Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie ever to be visited on the UK, the scale of national hand-wringing and self-flagellation would be unbearable. But in Hamburg a Saxon shrug was sufficient to cast prior worries aside and bask in the glory of the new £662m concert hall that was arguably Europe’s most celebrated cultural opening of the year.

To say that getting here was not easy is putting it mildly. The architect was appointed – unusually for such a major scheme – without a competition, the budget ballooned tenfold, completion was delayed by seven years, a lawsuit stopped construction for two years, contracts were torn up and replaced with new ones, and the entire project was mired in acrimony.

The irony is that with the exception of its spectacular auditorium and rooftop piazza, the eventual finished product – a retained brick stump underneath a largely faceless glass block sporting a Simpsons-esque bouffant roof – seems an oddly underwhelming, if enigmatic, conclusion to such an impassioned furore.

Its impact, however, was felt even on these shores – in particular when the Elbphilharmonie’s artistic director claimed that London’s size and status merited a similar concert hall here. He thereby waded into the long-running debate about whether the British capital needed a new symphony hall in the manner of Hamburg’s Elbphilharmonie and Jean Nouvel’s 2015 Philharmonie de Paris. The recent appointment of US firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro to draw up plans for said venue seems to indicate that the project is finally under way. Let’s just hope it doesn’t suffer the same troubled gestation as its German counterpart.

1 Readers' comment