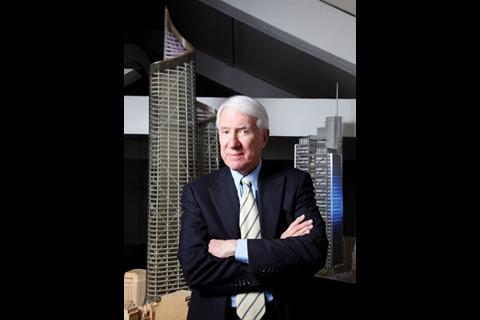

When the London office of Kohn Pedersen Fox was split in two by the departure of Lee Polisano in September, founding partner Gene Kohn did what any self-respecting 79 year old would – he moved from New York to London to sort the whole mess out himself. He tells Emily Wright the full story

With his shock of white hair and impeccable manners, meeting A Eugene Kohn feels like being transported back in time into an old black-and-white film. “Well, good morning to you,” he smiles, showing off a set of perfectly white teeth. “It is a real pleasure to be meeting you today.”

Kohn’s old school approach to meeting and greeting should come as no surprise. Best known as Gene, Kohn is the chairman and one of the three founding partners of architect Kohn Pedersen Fox (KPF), which he set up in 1976 with William Pedersen and the late Sheldon Fox.

He is also 79 years old. But don’t let that fool you. His finger-crushingly firm handshake speaks volumes and, white hair aside, he looks nowhere near his age. He certainly doesn’t feel it: “All your British articles want to tell me how old I am,” he laughs. “But I play basketball or baseball most weekends; I fly 300,000 miles a year and probably work harder than most people half my age. It’s not like I’m a surgeon,” he says earnestly with raised eyebrows. “Now, I can see why you wouldn’t want to be operated on by a 79-year-old surgeon.”

This is just as well. Since last autumn, KPF has gone through a turbulent, and very public, period of change caused by the dramatic exit of five partners from the London office, led by Lee Polisano. They set up their own practice, PLP Architecture, last September. And what Kohn announced just days later came as even more of a shock than the news of the split itself – that he would move to London run the office while it got back on its feet.

“Nobody was expecting it, I know. I decided to do it because I felt that the situation required a level of experience and sensitivity that only I could offer – as someone who contributed to the name over the door. I wanted to show I really cared.”

Six months on and Kohn is still integrating his methods of leadership and has not spoken to any of the “breakaway five” since they had final contact through lawyers in September. But he is keeping an eye on their progress, fully aware that everyone will be waiting with bated breath to see who will come out on top now that clients and staff have been more or less divvied up.

What went wrong?

Kohn talks with great pride about how his little New York architectural firm went global during the eighties. It expanded into Europe, with a specific focus on the UK before growing further in Asia and Japan. By 1989, KPF was winning big London projects, including two blocks of the Canary Wharf redevelopment. This was thanks to past experience designing large office buildings – something that wasn’t commonly found in the portfolios of many UK architects at the time. It soon became clear that opening an office closer to the work was going to be crucial. Two of the practice’s best young partners, including David Leventhal who would later become one of the breakaway five, were sent over to head the outfit.

For the past 25 years, the office has won good jobs and operated with great success. And that, says Kohn, has been part of the problem: “The London office, right from the start, was run differently from the New York office. I should have seen more clearly what might happen as a result. But it was doing well. And when something is successful, you get nervous about touching it.”

Unfortunately they released the news of the offer to staff and to the press before they discussed it with us. It caused uproar with clients

The eventual problems stemmed from two very different management techniques. In the States, Kohn and his partners advocated a leadership structure in which overall decisions were taken by Kohn as chairman, but not before any issues had been discussed with staff. And there was no focus on one headline name: “If someone worked on a job, it would be their name in the press,” he says. “Not mine. That shows everyone how many good people we had working for us, broadened our reputation and meant that clients knew they were getting the best team, even if they didn’t get me or Bill or Shelly.”

At the London office, however, Polisano was moving towards a more traditional top-down operation – or “holding everyone back”, as Kohn would argue. He adds that Polisano became territorial over projects, refusing to allow teams from the New York office to get involved in UK schemes, even if they could add value and experience: “I kept saying, when you hire KPF you should get the best,” says Kohn. “Depending on the project, sometimes the best for that job should have come from New York. But the London office didn’t want that and stopped taking advantage of the best expertise in the firm.”

By the middle of the last decade, KPF in London was increasingly pursuing projects alone: “There were schemes that could have gone better,” says Kohn. “The ones we never got. With dual expertise I believe we could have won more.”

The founding partners realised that, on top of losing projects, if they allowed the two branches to continue drifting apart, they might lose the London base altogether. So in early 2009, Kohn tried to persuade Polisano and his partners to come around to his way of thinking. In vain. In May 2009, Polisano, along with Leventhal, Fred Pilbrow, Karen Cook and Ron Baker, made an unofficial offer to purchase the office, which was turned down. “The offer was nowhere near enough,” says Kohn. “And Lee had indicated through letters that they would want to operate totally independently and share no ideas, no suggestions at all. Obviously we didn’t want that.”

“An official offer was made in June,” he says, adding that he was not impressed with how the situation was handled. “Unfortunately they released the news of the offer to the press and told staff before they discussed it with us. It caused uproar with clients, who were upset and wanted to know what was happening. You don’t air your dirty laundry until you have resolved it.”

Kohn and his team had to respond quickly, publicly turning down the offer and making it clear that it was not their intention to run the offices separately. By now, relationships were irreparably damaged. “It was a real mess,” says one City commentator. “What a falling out.”

Polisano has since described the formal proceedings that followed as “an amicable separation agreement”. But Kohn reckons the use of the word amicable is generous: “I did have a thing or two to say to them at the time about ethics and professionalism. They wanted to take all the contracts and all the staff and leave just the name behind.

But after nine weeks of very expensive lawyers, we ended up in agreement and they left on 15 September. I haven’t spoken to them since.”

A new order

I did have a thing or two to say to them at the time about ethics and professionalism. They wanted to take all the contracts and all the staff and leave just the name behind

As in any break-up, the weeks following the split were almost tougher than the split itself. The London office was in turmoil and Kohn took out a two-year lease on a London property and relocated. “It was a really, really good move,” says one high-profile UK architect. “Gene is one of the best marketers I’ve ever met. His decision to come over here made clients take notice. I am sure that there are some who stuck with KPF once they heard the news.”

“There are times when you need to just take action,” says Kohn about the move. “I have made mistakes in the past and have made the wrong decisions. That has kept me awake at night. Here I had to be firm and decisive and I did what I had to do. Something like this can have a profound effect on staff and they needed real leadership.”

Kohn held meetings as soon as he arrived and explained to each staff member what their options were and gave them the choice to stay or go: “Out of 170 people, we lost about 40 to PLP,” he says. “And we kept about 70% of the projects which, fee wise, probably works out as being more as we kept the biggest, like the Pinnacle and Heron Tower.”

He didn’t save them all, though. And the pressure is now on to ensure that KPF does not lose out to PLP in the long term, because Polisano and his team will be tough rivals. The breakaway firm managed to increase staff numbers from five to 65 in a matter of weeks and walked away with several high-profile projects for clients including Grosvenor in the UK and Mubadala in the Middle East. Polisano was quoted as saying in November: “All the projects that have come with us have been at the client’s request … that sends a very powerful message.”

Kohn is unfazed. He is confident that the London office will make a full recovery thanks to a new management system and a focus on international expansion in China and India, where he hopes to open a new office within the next year.

The new leadership system will be the same as Kohn advocated in New York. He has restructured the UK arm by bringing in a new layer of principals to add breadth to the leadership structure rather than having one overall boss. He says the atmosphere is already much improved, though he admits it will take a while for the Brits to get used to such a team-orientated system: “Lots of firms in the UK have one name at the top. Rogers is a bit different as it is more of a partnership, but you wouldn’t know there are 1,500 people working for Norman [Foster] because his name dominates. I have great admiration for him as an architect, but my firm is different. I think the lateral, New York model is better.”

The other thing on Kohn’s side is his reputation. He is well known and well respected and, for most people, his 79 years indicate a wealth of experience rather than a lack of vigour. Gerald Ronson, with whom KPF has been working on the Heron Tower in the City, says: “I first met Gene 20 years ago in New York and he is a gentleman. He is very engaged, very bright and responsible for delivering many iconic buildings around the world. When you talk about people in their 70s in the UK, you think about wrinkly old men. In the states it is different and you find a lot of major companies being headed up by guys in their 70s and 80s. If you’re in good health like Gene, it’s not an issue. I’m 70 and I work 12 to 18 hours a day.”

And let’s not forget that steely determination – almost as unforgiving as the cast-iron handshake: “I wish PLP luck. And there are no hard feelings. And I am sure they will do well and they will do good work. But we’ll be better, a lot better. We’re the toughest firm to beat here.”

Kohn’s big break

“I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and grew up there. I wanted to become a professional basketball player, but was never good enough so decided to be a sports broadcaster instead. My parents were pretty strict, though, and told me that wasn’t a suitable career path. So I began to consider architecture, though it wasn’t my passion. I studied for five years under [US cubist architect] Paul Rudolph and he began to get me excited about it – but if the New York Yankees should have offered me a place to play baseball I probably would have taken it!

“They didn’t, however, so I continued on my with my life. I did active duty in the navy for three years. And during the course of that, my unit ended up in Morocco. The navy were about to send some of the most high ranking officers out for a visit and when my captain found out I had studied architecture, he got me to redesign the old French naval club. I had two weeks and all the money and staff I needed – and did an initial sketch (see above). I focused on nothing else and it was a great success.

“And that was when I allowed myself to follow it as a career path and a passion. It wasn’t that I was resisting it up until then, it’s just when you grow up with a love for one thing, for me that was sports, it can be hard to push it to one side and focus on something different.”

No comments yet