We’re all more or less signed up to the government’s target of cutting 20% off costs in the next four years (or so we say). But how we do it is still the subject of fierce debate. Building asked three construction professionals what they would do

The construction industry could be forgiven for a sense of deja vu when, alongside the Budget in March, the government demanded it shave 10-20% off its costs over the next four years. Surely, some muttered, we’ve been here before: the Latham (1994) and Egan (1998) reports lambasted a fractured industry that failed to look after its customers, and proposed cutting costs by replacing a fragmented and litigious supply chain with an “integrated” one. But chief construction adviser Paul Morrell is still bemoaning lack of integration. Why should now be any different - and which of the government’s many ideas on how to achieve savings can really be implemented?

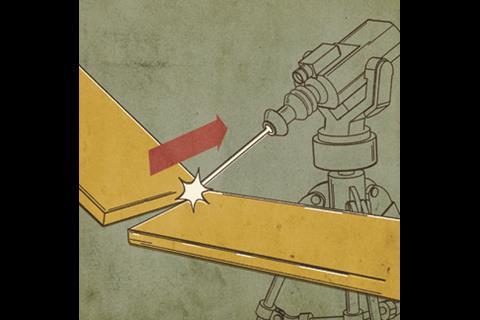

Integration is not the only money-saving idea to play with. For example, the government wants the industry to think harder about whole-life costing, to ensure buildings clock up savings throughout their lifetime. Standardisation is another part of the plan, and the James Review of school procurement, released this April, has demanded that schools be built from set designs and use off-site construction to create certain parts.

It will surely help that, instead of seeing the savings drive as a crushing target from above, almost everyone has lined up behind the government’s goal - except some sections of the architecture profession. Angela Brady, RIBA president-elect, has argued that imposing a standardised design across all schools, for example, could be a “short sighted, costly and dangerous exercise” because it will “cut out the possibility of good design and variety”. But others think that architects can be expensive. David Mathieson, head of public sector at Turner & Townsend, believes handing design to a contractor can cut up to 30% off the price of a school.

But 20% will have to come from somewhere - and who loses and wins will depend on how the industry chooses to do it. Here architect, contractor and consultant argue it out.

The contractor ’innovative thinking’

John Frankiewicz, chief executive officer, Willmott Dixon Capital Works

We’ve already proved we can achieve 20% cuts, but it relies on innovative thinking and good leadership from client and contractor alike.

We’ve invested in developing standardised designs to cut costs by 30%. The first going to market relate to education, and we are working on designs for the health and leisure sectors. This does not seek to undermine the work of architects; in fact we used several to develop our standard designs, but it does give clients a particular option when their budgets are being cut and the project is in doubt.

One barrier to standardisation is that contractors will not invest in intellectual property that can be used by a rival. We offer our standardised design through the Scape framework where we are sole contractor, and clients on other big frameworks must resolve how they can develop standardisation within a competitive tender process. However, the use of standard designs for certain projects is inevitable if we are to achieve more for less and squeeze out costs.

Another area is the co-location of facilities. For example, on a joint health and leisure complex for Gateshead Primary Care Trust and Gateshead council, we saved £1.2m in overall costs compared with the price of building both facilities individually, with savings from sharing the front entrance and atrium, combining M&E plant and services, landscaping and utility connection charges. Clients need to be receptive to this, and companies such as Willmott Dixon have acted like a strategic partner by making the case when they see it.

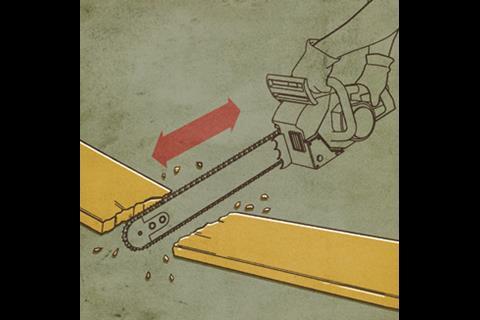

The government should also consider removing VAT on refurbishment work, as clients can achieve major savings by remodelling what they have. At Cheshire’s Macclesfield High School, where one-third was refurbished and the remaining added as new build, this produced a 22% saving against going down a total new build route, with a contract sum of £15.1m as against £19.5m for a new school.

The architect ’expertise should inform design’

Simon Allford, director, AHMM

The endlessly repetitive cycle of boom followed by bust followed by a call for reduced construction costs (this time 20%) is embarrassing both because we fail to rise to the challenge and because the challenge only arises when the market fails. Ironically, at that point of failure, as supply exceeds demand, you get the 20% off doing nothing!

Politics and progress demand, however, that we do not wait for this bottoming out to do the job for us. So what to do?

First, work for clients who understand value, accept responsibility and will consider risk and reward. Sadly, that counts governments out.

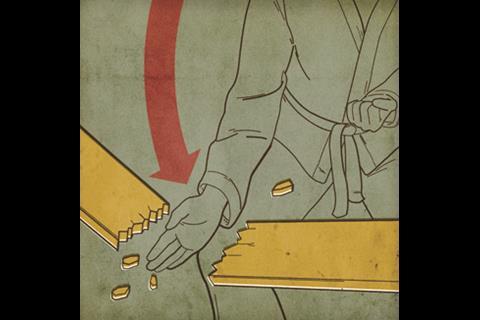

Then talk to the makers and users, so their expertise informs design and not the other way round. As risk also drives construction cost, get all the players’ interests aligned so client, contractor, consultant and constructor work together to ensure that each part of the project costs less and does more: working harder for longer both in construction and then in use. To facilitate this common cause, you must eradicate the ridiculously expensive legal agreements that clumsily constrain creative thinking.

Cost is also driven by misguided perceptions of what the market wants, by overdesign in response to over-regulation and by uncertainty over planning. So challenge the market by offering something leaner but better. Then measure your success using only a total project finance model that acknowledges the cost of construction, land and money; one that demonstrates value (cost over time) by considering quality, adaptability and cost in construction, in use and in energy.

Finally, be very certain that what you are delivering is also of delight, for when the market cycles into a bust and your building sits unhappily, unused and unloved, everyone will judge the cost of building failure and nobody will remember those crudely measured savings.

The consultant ’challenge the brief’

Ivan O’Toole, director, Capita Symonds

There are a number of areas where costs can be reduced. First, incentives should be provided throughout the supply chain to reduce costs and programme in a way that is realisable for the employer. This means that the procurement approach requires all parties to share in savings at each stage. The use of bonus payments could be a way to achieve this.

Second, a project team must analyse and challenge the brief to ensure that it does not change without good reason.

Third, standardisation and the division of labour is one of the fundamentals of the industrial age - standardised and mass production is the best way to reduce costs. This has been embraced by the industry to an extent and we see things like pre-made systems from cladding, plant rooms, bedrooms, toilet pods, service risers, various structural solutions.

But in order for this to have a real impact, it must be done on a grand scale and linked to the procurement model that is transparent and provides true incentives. There is the obvious argument that “no building is the same and shouldn’t be the same,” but why can’t certain parts be the same?

Finally, 3D design modelling has another part to play in the procurement, standardisation and brief development allowing co-ordinated information to be produced for all disciplines and throughout the design and construction process.

Of course, the real cost of owning and operating a building is not in its capital cost but in the whole-life cost. The intelligent response to the 20% issue would be to look at the total cost of owning and operating a building - energy, resources and workplace strategy (admin, payroll, IT support, flexible working).

While all of these techniques have their use, the biggest impact would be from a combination of standardisation linked to a procurement model that offers the right incentives so that savings are realised by the employer but also to the benefit of those who have provided the saving.

It can be done if the industry and government collaborate and invest in these principles - this requires commitment and may not be wholly realised in one parliament.

It also requires a capital programme - which is in question at the moment.

No comments yet