Building the right infrastructure is the key to tackling global poverty in an environmentally sustainable way – if we follow these steps …

In her powerful and radical book, Doughnut Economics, Kate Raworth argues for the rewriting of economic theory and social orthodoxies so that civilisation may live in perpetuity in a “safe and just space”. In this space, everyone, everywhere, has at least the minimum they need for a good quality of life – clean, fresh water, sufficient food, safe and affordable housing, good education and healthcare, personal safety and security, equality, and so on. But the consumption of these goods is bound by the sustainable capacity of the planet, whether in terms of mineral resources, carbon dioxide or the diversity of life on land, sea and air.

Construction cannot tackle the climate emergency unless we focus on strengthening our industry

Construction has a central role to play in helping the world to find that safe and just space – the UN has set out 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) that aim to end poverty and tackle climate change, and the majority of these depend on infrastructure. And it must do so quickly because, as we all now know, we do not have much time to get this right.

But we also know that the safety instructions on an aircraft say to put on your own oxygen mask before helping others with theirs. Construction cannot tackle the climate emergency unless we focus on strengthening our industry.

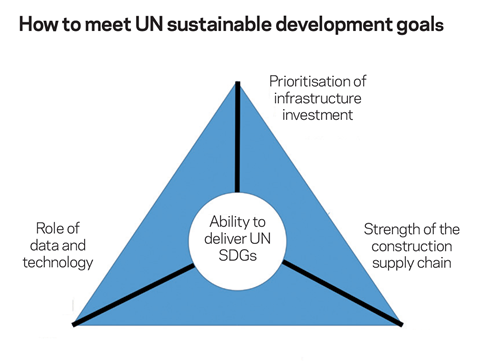

Raworth’s visualisation is a doughnut. Mine is a braced triangle (above). Less stylish perhaps, but more stable, as any engineer will appreciate. I see a powerful interdependency between the three points of my triangle.

- Prioritising the world’s eye-watering demand for new – and better-maintained existing – infrastructure which, being driven by population growth, urbanisation and climate change (mitigation and resilience) is not going to reduce in the next hundred years. We need to prioritise to optimise our scarce human, raw material and financial resources for the infrastructure that will have the greatest impact in delivering the SDGs and taking us into the safe and just space.

- The strength of the construction supply chain. Unfortunately, the industry’s ability to deliver is constrained by its seemingly systemic weakness. Addressing this depends on investment in the technology and skills of the future, which in turn depends on the fundamental reform of the procurement of infrastructure. It also requires enhancement of the capability of infrastructure owners and, in some countries, reform of regulatory and other governance structures.

- The role of data and technology, which if properly deployed would allow us to deliver more and better outcomes at lower human, material and financial cost. It would also allow us to make better decisions about what to focus on. Hong Kong’s Construction 2.0 initiative, which lays out the government’s vision for the construction industry, makes explicit the link between technology investment and industry efficiency.

In Davos, at the recent World Economic Forum, all these conversations were in play, but largely separately. It is time we brought them together to ensure a safe and just space in which the construction industry can perform. Here is my checklist for what we need to do:

One global methodology

Rationalise the plethora of standards for the assessment of environmental, social and governance impact of infrastructure projects and programmes so that, ultimately, we have a single globally-accepted, transparent, objective and measurable methodology. This will drive public policy, business investment decisions and the allocation of public and private capital towards the most sustainable investments.

Embrace collaboration

Embrace much more collaborative approaches to the procurement of infrastructure creation, maintenance, renewal and operation to make the supply chain more financially robust. These principles are laid out in the Institution of Civil Engineers’ Project 13, and largely mirrored in New Zealand’s construction accord. We also need to continue to focus effort on enhancing the knowledge and capability of organisations that buy infrastructure services, so they better appreciate the repercussions of their procurement strategies.

Innovation ecosystem

Support the development of an innovation ecosystem for construction to drive much higher levels of investment in technology. I visited the Consumer Electronics Show last month and was struck by the huge degree of start-up innovation in the transport sector. But venture capital money will remain hard to get for an industry that averages a 1% margin.

Share data

Support initiatives to share data, treating it – as the National Infrastructure Commission suggested – as a public good, so that governments and industry can be as informed as possible about how best to optimise our investment choices and execution. Data sharing also lies at the heart of the industry investing in a circular economy approach, building more flexible and recyclable assets and minimising raw material use.

All these actions require something else, too – the very highest capability in national and global governance to bring together the stakeholders that need to contribute and thrash out actions to which all can be held accountable. In the UK, that means the industry uniting behind one body – the Construction Leadership Council – and leaning in to play our part in addressing the world’s biggest challenges.

Richard Threlfall is global head of infrastructure at KPMG

No comments yet