As the debate on UK runway capacity gets ever more intense, all of the UK’s airports are focusing on how they can use their existing assets more effectively. Paul Willis and Simon Rawlinson of EC Harris review the key issues affecting infrastructure replacement and enhancement

01/ INTRODUCTION

Aviation makes a key contribution to the global economy, but its operations and facilities are frequently challenged with regards to their impact on the environment - making rapid investment difficult to deliver. Aviation and associated support services contribute 1.5% to UK GDP, worth £18bn per year. Aviation has a key role in facilitating tourism too - which alone represents 10% of the UK economy.

Infrastructure projects are widely seen as a means of kick-starting the economy. Air infrastructure is particularly important as a construction opportunity and in facilitating aviation as a wider economic catalyst.

As the UK moves towards recovery, aviation’s unique contribution to rapid economic growth in a globalised economy will be very important - facilitating direct exports, encouraging inward investment and helping regions sell goods and services in new markets. The role of direct flights, supported by sufficient airport capacity, is crucial, and this is an area where the UK needs to invest. A recent British Chamber of Commerce study revealed the importance of direct flight links to business leaders in Brazil, China and other growth economies when making investment decisions.

While 60% of UK air traffic is focused on the regulated airports in the South-east - Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted - regional airports are investing to capture a share of these growing markets. Airports including Birmingham, Edinburgh and East Midlands are proposing runway extensions and other infrastructure investments to extend their capability to host long-haul flights.

The high profile of the current debate on increased runway capacity in the South-east is a reflection of the high economic and political stakes involved and the long-term nature of these decisions. If approved, “Boris Island” would probably not open before 2028 and a third Heathrow runway could take six to 10 years to construct, so neither option will immediately address capacity and service issues affecting UK airports.

By contrast, there are a wide range of much smaller projects that need to be undertaken to address short and medium-term operational priorities in the context of existing runway capacity. Most of these projects will be on a much smaller scale than the investment carried out at airports across the UK over the past 10-15 years, and an increasing number involve the upgrade and adaptation of relatively new assets, often in reaction to changes in business requirements as well as asset condition. The ability to programme the adaptation and upgrading of existing operational infrastructure cost-effectively and with minimal disruption will be absolutely crucial to success in the next investment period.

02 / CHANGES IN AIRPORT MARKETS

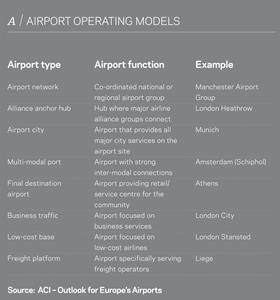

The market for airports and airline operators has changed very significantly over the past 10 to 15 years and will continue to evolve rapidly. Figure A (below) illustrates the range of airport operating models that currently compete in the UK and Europe. Major changes facilitated by de-regulation include the growth of the budget airlines, the impact of e-commerce, the establishment of powerful alliances among a consolidated group of major airlines and the emergence of fast-growing international carriers such as Emirates as equally powerful competitors.

An illustration of how some of these changes affect investment can be seen in baggage handling. Typically, baggage handling demands increase in line with traffic volumes. However, with budget airlines encouraging cabin rather than hold baggage, pressure in many airports has transferred to passenger hand baggage screening. At the same time, with the widespread use of internet check-in, departing passengers increasingly allow less time for baggage check at the airport. As a result, systems must process hold baggage quickly and efficiently in order to optimise the time from bag drop to aircraft - mitigating the risk of delay. Changing customer behaviour and airline service innovation requires new service standards and additional investment, but creates real competitive advantage through improved service quality.

Similarly, airline mergers or changes to alliance membership, which drive changes to the location and colocation of airlines across the airport, can generate unforeseen investment priorities, with most of the benefit secured by the airlines.

As user demands such as enhanced service quality have grown, the public sector has also stepped away from investment in airport infrastructure. The business model for airports has transformed into the delivery of a highly competitive, self-financed range of business services. The 2008 financial crisis accelerated the evolution of this model, with airlines becoming more cost-conscious, consolidation of the ownership of airports and accelerating competition among airports to secure traffic from emerging economies. Away from regulated airports such as Heathrow, well-established and footloose airlines are driving competition between airports over landing charges, service standards and investment priorities.

03 / UK AVIATION INVESTMENT PRIORITIES

Over the next five years the level of investment at UK airports is likely to be in the region of £7bn. Given long-term uncertainty and short-term investment priorities, airport infrastructure investment is likely to be focused on the following key areas:

- Passenger experience Investment in the passenger experience has been a key priority for regulated and non-regulated airports - driving substantial investment in terminal facilities, transport infrastructure and so on. The regulator is putting more emphasis on the passenger experience, and airport operators are looking to differentiate themselves.The provision of improved leisure, retail, food and beverage offerings will therefore continue to be priorities, particularly as non-aeronautical revenues are essential to supplement landing charge income, accounting for an average of 48% of revenues at European airports. Increasingly the challenge will be to deliver the improvement in operational facilities. The recent upgrades to Gatwick and the overhaul of Heathrow Terminal 4 for the Star Alliance illustrate the potential for transformation of existing facilities.

- Asset replacement Asset management and asset replacement investment is concerned with maintaining existing levels of performance and operating the asset to an acceptable level of system failure.It is anticipated that asset replacement will account for up to 30% of the planned investment in airports over the next five years. Investment prioritisation and stakeholder management issues associated with asset management, involving airlines, third parties and the regulator are highly complex. Regulated airports operating with a Regulated Asset Base (RAB, see section 4 below) will be required to provide greater transparency in connection with the agreement of planned levels of expenditure, so that the prioritisation of investment can be clearly demonstrated to airlines. To achieve this, operators need a detailed understanding of the baseline condition of their existing assets and how their operation or failure could impact on the services offered by airport users.

- Capacity improvement and responses to legislation Investments in capacity improvement are being undertaken to ensure that forecast demands can be met. Requirements of new national and international security legislation also need to be accommodated. Runways and taxiways are being improved to raise operational efficiency and address constraints on take-off weight. Alterations to stands and aprons are being made to change the fleet mix that an airport can accommodate and to improve turnaround time.

- Passenger terminal facilities are also being upgraded to increase throughput. The upgrading of passenger security screening with smart lane technology is an example where investment has returned an immediate benefit, increasing throughput by 25% and reducing passenger delays and waiting times.

- Resilience Resilience investments associated with extreme weather or unplanned events are also an important area, as the reputational risk is substantial. However, under both the regulatory model and typical competitive conditions, airport operators are not incentivised to make these investments. While expenditure on additional plant for the removal of snow and so on becomes a priority once a major disruptive event has taken place, it is much harder to justify as “risk mitigation”.

- Airport operators also need to make systems more resilient to day-to-day problems such as air traffic control delays, particularly as runway capacity limits are approached. Examples of ways in which additional capacity can be built in include diverse taxiway routings, back-up baggage handling systems and hard standings for temporary passenger facilities. Airport operators are also investing in predictive tools and other technologies to analysis the consequences of extreme events - enabling responses to be pre-planned and optimised.

Business challenges

- Airport operators can see the opportunities associated with sustained growth in volumes of traffic. European air traffic volumes are forecast by Boeing to grow by an average of 4-5% per year between 2012 and 2030. However, in addition to uncertainty around the timing of forecasts and popular support for airport expansion, there are a number of challenges in the business environment faced by airport operators, which currently limit their willingness to invest. These include:

- Ability to recover operating costs from airlines According to Airports Council International, landing charges do not cover the full costs of airport infrastructure. Europe-wide data shows that the deficit is currently around €4bn per year. With more stringent security and resilience requirements, this gap is likely to increase. Airports plug the gap with revenues from wider commercial activities such as retail, car parking, food and real estate development, reducing the potential for uplift in profitability from these sources, and in turn reducing the attractiveness of the investment.

- UK competitive disadvantage UK airports have identified airport regulation and the tax system as sources of disadvantage in the European aviation market. Regulation by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) will be reformed ahead of the next pricing period commencing in April 2014. Tax is highly controversial, not only because of recent increases to air passenger duty (APD) affecting flights into and out of the UK, but also due to the introduction of the EU ETS carbon trading scheme this year.

- Stability of airlines Sluggish growth in key eurozone markets, intense competition and high fuel costs are having a significant effect on airline profitability and performance. Airline failure and further airline consolidation - such as BA’s recent takeover of BMi - could affect the routes and volume of traffic served by an airport, dramatically affecting revenues.

- Access to capital Airports face similar challenges in raising project finance as other large-scale infrastructure developers.

04 / AVIATION SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES

Aviation’s high-profile social and environmental impacts are increasingly accounted for and mitigated - requiring investment from airports as well as airlines. Aviation currently contributes 3% to global greenhouse gas emissions, and targets have been set both globally and locally to progressively reduce emissions related to flight and ground operations.

The UK’s target for aviation-related greenhouse gas emissions is for levels to return to 2005 levels by 2050, taking into account significant growth in passenger volumes. The plan is that the reduction will be achieved mainly through a combination of more efficient planes and engines and use of bio-fuels.

Other initiatives requiring on-airport capital investment include the Aircraft on the Ground Initiative (AGR) which requires investment in power and conditioned air supplies at stands, and low-carbon passenger and staff transportation systems. Some 70% of UK airports have adopted AGR initiatives. Long-term changes in air traffic control standards, such as “economic descent speeds” will also reduce fuel consumption and emissions, and should have noise benefits too.

05 / REGULATION OF AIRPORTS IN THE UK

UK airports are currently regulated by the CAA under the Airports Act 1986. The regulator’s role includes recommending levels of airport charges for three designated airports: Heathrow, Gatwick and Stansted. As these airports account for over 60% of passenger traffic in the UK, the CAA’s influence on service quality standards and customer expectations is substantial. The current regime was defined before the emergence of budget airlines; the ongoing break-up of BAA is also changing the regulatory requirement. The current scheme is due to be replaced ahead of the 2014 price review.

The CAA’s economic regulatory functions include:

- To further the reasonable interest of users of airports, both airlines and passengers within the UK

- To promote the efficient, economic and profitable operation of the airports

- To encourage investment in new facilities at airports in time to satisfy anticipated demand. Regulated Airport Charges are determined by the setting of a price cap – that is, the maximum revenue per passenger that the airport can levy through airport charges.

In addition to setting charges, the regulatory model also drives airport performance through the inclusion of service quality measures. These motivate investment in capacity and the quality of the airport environment. Regulated airports can be financially penalised for poor performance. Service measures include availability of facilities such as air-bridges, queuing time notices for security screening, clarity of way-finding and cleanliness.

UK prices are set using a single-till RAB approach, whereby the airport operator is allowed to make a given return on its investment in regulated assets including a return on future forecasted capital expenditure, plus amounts for annual asset depreciation and operating costs. In the next price review period, and as a consequence of many years of high levels of capital expenditure, the CAA is expected to focus far more on demonstrating the value of expenditure on the existing asset base.

Issues with the regulatory model include:

- The charge model drives “one size fits all” investment solutions that might not suit all users’ requirements - budget airlines have been vocal in theiropposition to some agreed investment programmes at regulated airports

- Once the “predict and provide” investment programme is agreed, it has to be delivered during the price control period - whether expected demand materialises or not. This also inhibits responsive investment to changes in the business environment

- The lack of transparency over the extent of and cost of work to maintain the value of the existing asset base.

Legislation to change the regulatory model is currently in parliament and will give the CAA more flexibility to devise regulatory schemes that address the needs of specific airports, placing greater priority on service quality. Possible outcomes could include longer price review periods for very large capital investment programmes, and even the establishment of competition between terminals at larger airports.

06 / PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND PROCUREMENT

Work on airports has a range of additional cost drivers associated with operational and security concerns. As the balance of the work shifts to more extensive asset replacement and adaptation work, management of these drivers will become even more important to protect the financial interests of the airport owner. Asset replacement works are more likely to have to be managed around the operational patterns of the airport - necessitating out-of-hours working, double-handling of materials, high regard for health and safety issues and effective change-over-up at shift ends. Work on airfield infrastructure, such as runway rehabilitation, is also subject to weather delay and logistical constraints.

Airside working

Security clearance is a key issue here, and processing of labour and materials can be a potential source of significant delay and extra bureaucracy. Contractors tend to use the same supply chains, as they already have security clearance and trained operatives, albeit that competitive pressure may be reduced. Airside working adds significant costs to projects, and wherever possible, work areas should be configured so they can be managed as landside projects with conventional operational procedures. Requirements and restrictions associated with airside working include:

- Additional costs of third party legal liability insurance

- Cost of training associated with driving and work permits

- Maintenance of airside fence integrity, including costs of security

- Control of airborne dust and debris to avoid ingestion by aircraft engines

- Vibration limits when working in proximity to sensitive buildings

- Remote facilities, including welfare, administration, storage and parking

- Out-of-hours working and phased development to minimise disruption to passengers and aircraft

- Controls on delivery and construction traffic to prevent airport road congestion.

Asset management

There are a very large number of stakeholders involved in airport operation, with interests ranging from security, passport and customs control, through the operational and commercial interests of multiple airlines to the needs of owners and investors. These priorities can be subject to rapid change - as a result of crisis, legislation or business change such as an airline merger. Different parts of the operator business are also likely to have different perceptions of operational risks and investment priorities.With so many interests to be reconciled, prioritising investment and asset replacement strategies is challenging, particularly on designated airports where the relationship between the investment and the benefit to the asset base will need to be demonstrated to the regulator.

A key enabler of effective investment and stakeholder management is likely to be the asset management strategy - designed to deliver the optimum value from an organisation’s full range of physical and economic assets, while taking into account mandatory operational and safety requirements. Asset management has been widely adopted in some areas of transport infrastructure such as roads, but whilst the focus in aviation has been on major projects delivery, pro-active asset management has received a lower priority. Given the changing mix of workload, complexity of airport systems operation, the client’s need to prioritise investment and provide line-of-sight justification of programmes, formal asset management systems based on standards such as PAS 55 are increasingly becoming a key tool in the management of proposed investment programmes.

07 / COST MODEL AND BENCHMARKS

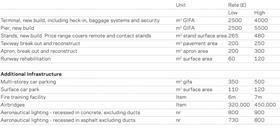

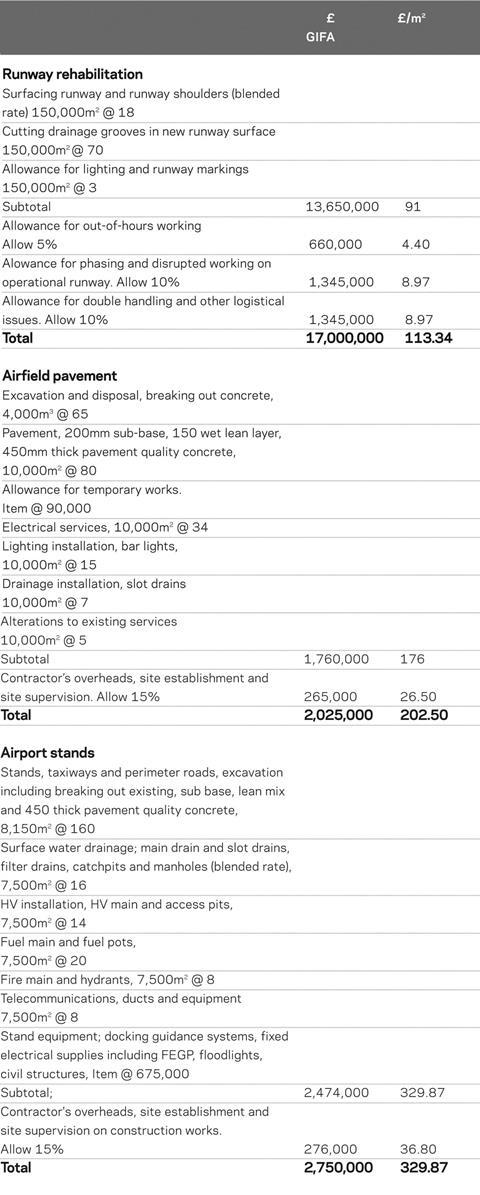

The cost model sets out indicative cost breakdowns for key elements of airport infrastructure including taxiways and stands, as well as runway re-instatement. The costs are based on an average UK location at second quarter 2012 price levels. The quantities used are representative of typical project sizes for larger airports.

The costs include contractor management costs and overhead and profit, factoring in allowances for airside working. They exclude allowances for project and programme risk, professional fees and the client’s internal management costs. VAT is also excluded.

Where the work involves close coordination with the operational demands of the airport, allowances for out-of-hours working and phasing have been included in the costs. Elsewhere, the costs have been prepared on the basis that works can be undertaken in normal working hours with minimal disruption or double handling of materials.

Adjustment should be made to the costs detailed in the model to account for variations in phasing, specification, site conditions, programme and market conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Fiona Gordon, Gary Empson, Yusuf Sharif and Mat Riley of the EC Harris Specialist Airports Group for their contribution to this article

No comments yet