There are many who believe that the lit appearance of an interior, or indeed exterior, will affect business performance. For example an exclusive restaurant would be lit differently to a fast-food outlet. The lit appearance could affect its popularity and hence its turnover and profit. Another simple example is how a space appears when lit by an overcast sky or by a combination of skylight and sunlight. The latter tends to give the occupants a greater sense of well-being that almost certainly reflects on productivity, perhaps not directly, but through a better attitude to work, which could reduce sickness and absenteeism.

The cost of an installation is another important issue; but here it is necessary to consider not only the capital cost but also the running costs, which include the cost of energy consumption and maintenance.

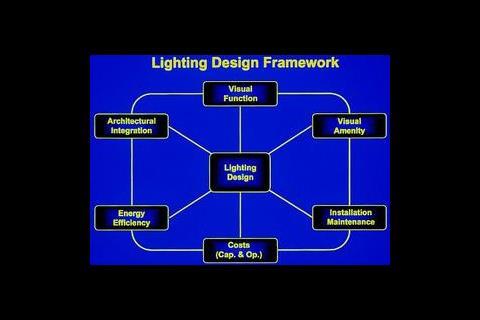

The need to approach lighting design in a holistic way is not only a requirement for the designer but also a requirement for the client if they are to get value for money. This has led to the proposal of the following design framework (see figure 1) showing the main elements that need to be addressed – perhaps not equally, but this will depend on the particular application.

Considering each of the elements individually and in combination, means the best solution for the particular situation is likely to result.

Most of the elements are self explanatory, but visual amenity (ie pleasant visual conditions), and architectural integration deserve further discussion.

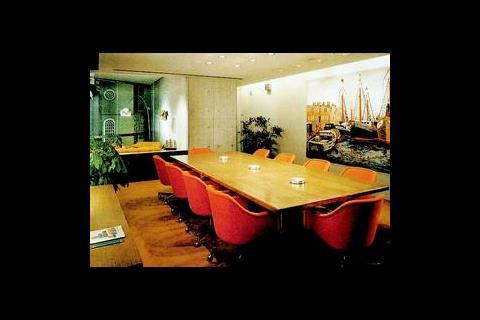

There is no doubt that lighting is an integral part of architecture and needs to develop naturally from it. This applies to the appearance and installation of lighting equipment, including lamps, luminaires and lighting controls. It also applies to the light pattern it produces.

A light pattern needs to reinforce the architectural theme, to respond to the shape and form of the interior and to the hierarchy of adjoining spaces. It also needs to respond to the finish, reflectance and colour of room surfaces. Overall good lighting should not be noticed in its own right except perhaps when it is used to draw attention to something, as in a display, or as a decorative feature. The installation pictured here (left) is a good example where architectural integration and lighting appearance form an important aspect of the design.

There remains the question of visual amenity, which in some ways is the most difficult to understand and accommodate. Some designers have a natural sensitivity for what is required, but most do not. It was this problem which led to a programme of research, carried out at the Bartlett, University College London, which started in the late 1970s. The aim was to try to understand how people respond to light patterns and the patterns they prefer for an office application. Also, if possible, to find a way of quantifying them.

The investigation was carried out in a number of stages and involved showing groups of people an interior lit in a variety of different ways, and asking them to make subjective judgements of the lit appearance. Physical light measurements were also made to attempt to find a link between measurement and appearance.

There are many who believe that the lit appearance of a building’s interior, or indeed exterior, will affect business performance.

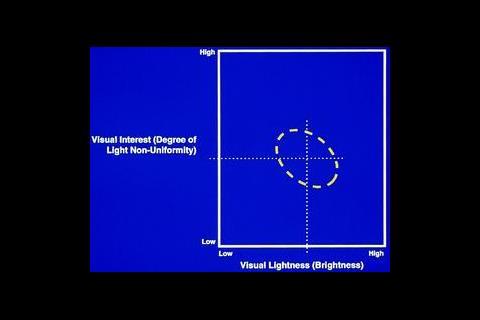

Early in the investigation1, it was found that people responded to two main criteria. These were labelled visual lightness and visual interest. Visual lightness described the overall lightness of the interior, while visual interest referred to a degree of non-uniformity in the light pattern, ie light and shade. It was also found that the occupants required a degree of both elements for the lighting appearance to be acceptable. In other words it was not sufficient for the space to just appear 'light' it also needed to have some degree of visual interest and vice-versa.

The general result is shown in figure 2 for one application type. Another point that emerged was that people preferred installations that comprised a number of different lighting elements, ie general lighting and accent lighting particularly. What they did not like was regular arrays of ceiling-mounted luminaires providing a uniform light pattern.

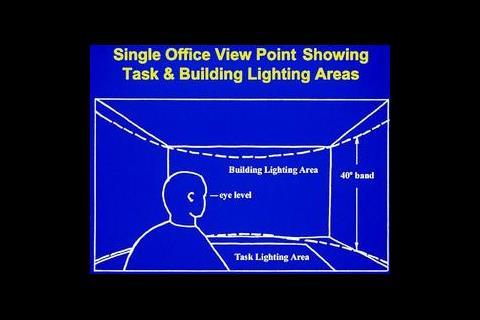

Later studies2, 3 showed that these two criteria can be described numerically by the average luminance and the luminance variation in a horizontal band 40° wide and centred at normal eye height (figure 3). This zone is the area that covers the main part of the people's normal visual field as they look and move about a space, or talk to colleagues – it is not the normal task area.

The most recent work has indicated minimum values, and that these criteria can be calculated at the design stage using computer visualisation programs, though there is still much work to be done to refine this process. However what the work has consistently shown is that people like a space to have a degree of visual lightness and visual interest, which together provide a visual amenity for the occupants.

As mentioned earlier, it is believed that the numerical combination will vary depending on the application, ie the lighting appearance required for, say, a leisure application would be different to an office and different again to an industrial situation, but this has not been tested.

So what is the value of the experimental work? It is almost certain that this approach to design will be more costly in terms of the installation. This means that the designer needs to show that there is independent evidence to provide justification. The experimental work described goes some way to achieve this, but what we have not been able to show so far, is that there will be human productivity benefits, although there have been many anecdotal reports to indicate this.

However, there is the potential for tangible benefits in reduced energy consumption. Take for example an office, with the work station lit independently to provide good visual function from free-standing or workstation-attached lighting equipment, with circulation areas in between lit to a lower illuminance and walls lit separately to provide visual lightness. Then the likely overall effect would be reduced lower energy consumption as compared to a conventional approach; perhaps by as much as 30-40%.

Further user/energy consumption benefits would accrue if users were provided with their own task-lighting illuminance control and absence-switching occupancy control. A further benefit would be reduced costs: if the work station needed to be moved the lighting could move with it, see opposite.

This is not the only solution, but by considering both task and building lighting, as indicated in figure 3, then a solution that provides good task lighting as well as an appropriate visual appearance should result4, 5.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Reference

References

1Hawkes R J, Loe D L and Rowlands E. 'A note to the understanding of lighting quality'. J.Illum.Eng.Soc. (USA) 8(2) 111-120 (1979).

2Loe D L, Mansfield K P and Rowlands E. 'Appearance of a lit environment and its relevance in lighting design: Experimental study'. Lighting Res. Technol. 26(3) 119-133 (1994).

3Loe D L, Mansfield K P and Rowlands E. 'A step in quantifying the appearance of a lit scene'. Lighting Res. Technol. 32(4) 213-222 (2000).

4Energy Efficiency Best Practice programme. Good Practice Guide 272: Lighting for people, energy efficiency and architecture – an overview of lighting requirements and design. EEBPp (1999).

5Littlefair P, Slater A, Perry M, Graves H and Jaunzens D. BRE Report 415 Office Lighting. Available from www.brebookshop.co.uk.

Postscript

David Loe is a BRE lighting consultant.

No comments yet