Whitby Bird & Partners has been involved in the services and structural design of nine PFI schools completed within the last 18 months. These comprise the five grouped schools at Peacehaven in East Sussex, three schools in the London borough of Newham and a single school at Redbridge. The consultancy is currently working on schemes at various stages of the PFI process including grouped schools schemes in Derbyshire and Scotland, with a total construction value in excess of £80 million. After working with PFI for five years, the practice has begun evaluating its experience of the process and the quality of the final product.

From the perspective of the environmental engineer, the design of schools focuses on the delivery of comfortable and stimulating learning environments that improve the educational achievement of pupils and the effectiveness of staff. The key to the delivery of these objectives is the provision of access to natural light and effective ventilation to limit summer overheating and overcome any lack of fresh air in winter. Such provision needs to take place in the context of an integrated approach to structural and services engineering.

Modelling for best design

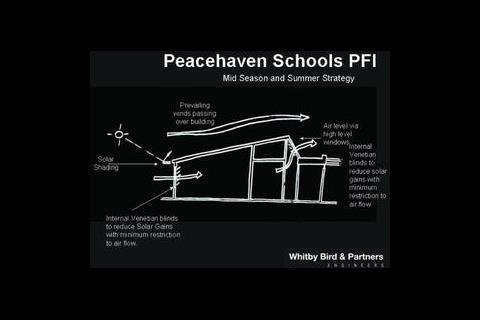

For all our designs of PFI schools, our building physics team have used cfd thermal modelling to examine the effect of window size and configuration as well as classroom depth, room height, solar shading and thermal mass on the maximum temperature conditions within the space. They also analysed indoor air quality during extreme winter conditions to ensure effective, draft free ventilation and evaluated the optimum thermal performance of the building envelope. Daylight analysis was carried out using the Lightscape modelling package to investigate the daylight factors that would result from particular window designs and room depths. The daylight and ventilation at Peacehaven have attracted comment from CABE, who wrote after a recent visit of the 'high levels of natural lighting and natural ventilation'.

By assembling modelling data on temperature, ventilation and light distribution for all the teaching spaces with their different orientations within the building plans, it was possible to produce optimum conditions for learning and teaching throughout. This data also allowed the long-term implications for building performance to be considered and to work at speed in the early design stages – important requirements when working within PFI.

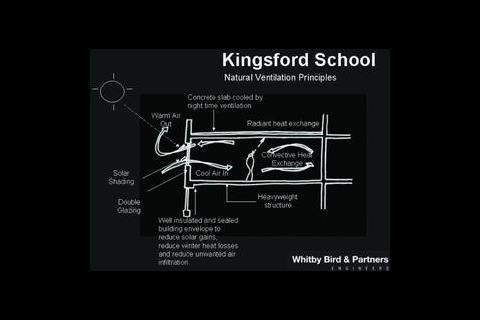

Whitby Bird was enthusiastic about PFI from the outset as it emphasised both capital building costs and operating budgets. This promotes the use of life cycle costing techniques when considering design options rather than the choice of the lowest first cost option. Our design approach on the schools projects has been to invest heavily in passive design features – thermal insulation, solar protection and exposed thermal mass of the concrete soffits – in order to allow the specification of lean, simple and robust mechanical systems coupled with simple and elegant structures.

This investment in the building fabric means that the internal environment is not subject to rapid deterioration should there be a plant or power failure, and minimises the annual energy and maintenance costs. As a result, all of the Peacehaven and Newham schools obtained band B or better SEAM ratings, with energy usage an average 70% that of equivalent best practice schools. We are currently planning to take this further on future projects, designing buildings to achieve a band A rating, with energy usage predicted to be 65% of best practice.

We are tracking the performance of our designs through a combination of building management systems and feedback through our own post occupancy evaluation process. In the long-term, the facilities managers will also be providing feedback data, and this will be used to further refine designs.

Consolidating schools' design within PFI In response to the scale of the PFI schools' development programme, Whitby Bird and the other project partners have developed a multi-disciplinary schools' design and construction guide. This is informed by all the design and construction disciplines together with facilities management, legal and financial perspectives. It aims to capture best practice and illustrate standard approaches to typical problems.

The guide is not prescriptive, recognising that there will be site specific issues with each scheme. It is intended to ensure that the team does not reinvent the wheel during the Invitation to Negotiate (ITN) stage, but uses the limited time available to unlock the specific opportunities inherent in the project, such as ideas that generate third party revenue. The guide considers the school as a series of elemental components including general classrooms, science labs, dining room, sports hall and main hall. These can be assembled as building blocks into a form – street, courtyard and/or radial – to provide the accommodation required by the client's brief.

The default environmental control strategy is natural ventilation together with passive building design that responds to the site and maximises the building fabric as climate moderator. A building physics approach has also been used to develop rules relating to the extent of windows, solar control, height and depth of room, occupancy density, magnitude of internal gains, and sound insulation to determine when mechanical ventilation or comfort cooling will be required. For instance, dining rooms are characterised by high occupancy densities and deep plan spaces and require mechanical ventilation to ensure effective, draft free ventilation in winter.

Lifecycle costing spreadsheets have been developed with the facilities management operators to determine the conditions under which specific capital enhancements such as lighting management systems, condensing boilers, heat recovery and rainwater recycling become financially viable. The calculations can be done relatively quickly for each site to take account of degree days, hours of operation, school population and energy costs locally.

We have developed standardised structural and services approaches to key room types such as laboratories and sports halls.

Exposing the structural soffit imposes a discipline on services layouts within the rooms and requires detailed consideration of conduit and pipework routes in order obtain the appropriate standard of visual co-ordination. Modular plant and equipment layouts, which can be scaled up or down to suit the specific plant duties at the site, have been worked up with the m&e installation contractors.

A response to PFI projects

Whitby Bird has had a very favourable experience of PFI schools projects, possibly because of our extensive experience of schools design and because, as part of a multidisciplinary practice, our engineers are used to working closely with their colleagues producing whole building solutions. This is a design philosophy that works well within a procurement ethos based on partnering and whole life costing.

However, there are well publicised criticisms of PFI to be acknowledged, not least of which is the issue of time constraints at ITN stage. Given a longer design period there would be greater possibilities for innovation and for refining elements of design.

It has to be acknowledged, however, that the contractors and facilities managers who lead the process are, in general, risk averse, so innovation might never become a feature of PFI projects.

Another criticism of PFI is that the complexity of the procurement process can sideline design. Clients – who may be inexperienced – have to deal with a large number of bidding teams, all of which are much larger than traditional design teams. In a situation where every member of the team has to win over the client, design issues can get demoted in favour of legal or financial matters.

PFI, however, is simply a method of procurement and need not work against time-honoured principles of good design. Successful project delivery inevitably relies heavily on the quality of all those involved. This is especially true in relation to the client, who is responsible for formulating an output specification that will secure strong, competitive bids while ensuring quality.

The design watchdog, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, has recently launched a client guide Achieving well designed schools through PFI 1, which is a handbook on how to navigate the PFI process and ensure good design. The government is also looking to reduce bid costs by standardising commercial and legal conditions and this is also to be welcomed.

It is still early days but our experiences to date suggest that the PFI process has the potential to deliver schools that are a credit to our industry.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

Reference

1 Achieving well designed schools through PFI, September 2002. Copies can be dowloaded from www.cabe.org.uk

Postscript

Andy Keelin is head of building services at Whitby Bird & Partners.

No comments yet