Air-handling became an art form in New York this summer, with the premiere of an opera in which scent was the star

The highlight of this summer’s New York cultural calendar was the premier of a new opera. But this was no ordinary musical drama; for a start it was performed in a darkened room in the Guggenheim Museum, rather than under spotlights at the Metropolitan Opera House. Stranger still, the success of each performance depended on an innovative building services design. But the really odd thing about this show was that it had no cast. The characters in the pre-recorded piece were represented by individual scents; this was an opera designed to be smelled rather than watched.

Green Aria: a ScentOpera was the idea of former financier Stewart Matthew, whose libretto was set to smell by Mohican-haired French fragrance designer and top “nose” Christophe Laudamiel. The plot is about technology joining forces with nature, but there is no spoken or sung script.

Laudamiel spent many months crafting an individual scent for each of the 35 “characters”, which are introduced to the audience at the start of the performance. They include Magma, which smelled like hot tar, Absolute Zero, Meretricious Green, and Shiny Steel. Laudamiel’s scents were accompanied by Nico Muhly and Valgeir Sigurdsson’s musical score.

The most difficult task, however, was not creating the scents but coming up with a way to get them to the audience in time to the music.

For the olfactory experience to succeed the entire audience had to receive the same scent at the same time at the same intensity. Achieving this was not easy because smells have a longer resonance in the nose than sounds do in the ear. What’s more, it was essential that the smells did not merge with each other to form an amorphous fug.

To find a solution, Matthew and Laudamiel turned to air movement specialist Fläkt Woods.

Ian Watts, the firm’s business development manager, was the man tasked with meeting this curious brief. “It did sound a bit off the wall,” he recalls. The idea of adding a fragrance to a room is not new – firms have been known to waft the scent of pine through the air-conditioning to energise their staff and some supermarkets blast the odour of freshly baked bread through the ventilation ductwork to increase sales.

Watts’ challenge, however, was much more complicated than just filling a room with one smell. He says introducing scent through the ductwork is fine for large spaces, but his brief called for short bursts of a succession of scents, each distinct from its predecessor.

The solution took 18 months to develop. Rather than using ductwork, the scents are delivered to the audience through what Watts calls “scent microphones”. These are small, goose-necked, semi-rigid tubes attached to each chair, which are adjustable to enable scents to be released close to the occupant’s nose. The designers experimented with various air velocities before settling on 0.2m/s. “We wanted each scent to emerge as a soft breeze with a minimum of turbulence so that people knew where the scent had come from,” explains Watts. “This speed was found to be the most comfortable.”

With the method of delivery sorted, the next task was to find a way of getting the scents to the microphones. Laudamiel wanted something capable of delivering a total of 35 different scents to each member of the audience in bursts lasting no longer than six seconds.

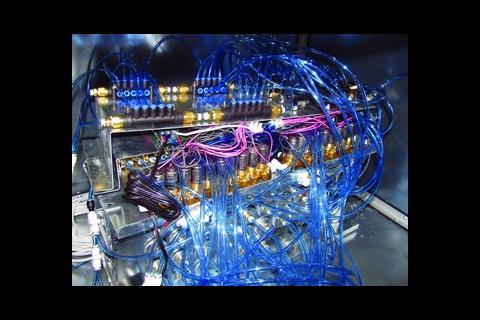

Unsurprisingly there were nothing suitable on the market, so Fläkt Woods developed a device that Watts calls a scent organ. This is a freestanding unit that uses a combination of compressed air and concentrated perfumes to deliver up to 35 scents to 25 “microphones”. (Six scent organs were used for the New York performances.) The scents are contained in specially manufactured cylinders, designed to prevent any cross-contamination between scents, which slot into individual housings in the scent organ.

“We used dry scents rather than wet scents,” Watts explains. Dry scents are based on crystals (rather than scent oils in an alcohol solution) because the smell from crystals evaporates more quickly than that contained in liquids or oils – thus allowing one scent to be replaced rapidly by another. The crystals are mixed with oil, forming a white slurry, which is then placed into its own cylinder.

Each scent is delivered through a complex system of manifolds and valves. Compressed air (at 150psi) is supplied to the scent organ via a pressure-regulating valve before passing into a distribution manifold which splits the air evenly between a further four manifolds. Each of these manifolds has 10 air outlets, each individually controlled by an electro-pneumatic valve, which opens to allow compressed air to enter a scent cartridge and bubble through the slurry, picking up the scent. The valves are controlled by a building management system of the type more often used to flash the lights on a nightclub dance floor.

To control the intensity of the smell, the organ includes flow regulators and bleed-valves. The scented air then enters an exit manifold where it is divided equally between the 25 individual scent microphone feeds. The microphones are connected to the manifold by tubes made of a special type of plastic, impermeable to odour. Each tube is exactly the same length to ensure the scents reach the nose of every audience member at exactly the same time.

A further slug of (unscented) compressed air is then injected into the manifold to push the fragrant air down the tube to the microphones and the waiting noses. This additional air has the benefit of purging the manifold and its connecting tubes of any residual scent.

The system was tested in the Fläkt Woods’ Colchester boardroom, which was commandeered by Watts and the team for the occasion. It worked; the scents were delivered in time to the opera’s pre-recorded sound track.

But the real test came at New York’s Guggenheim Museum. To cater for an audience of 148, Fläkt Woods had to position six scent organs strategically around the auditorium, fed from a ring-main of compressed air. “We’d done a lot of testing at Fläkt Woods’ factory but we did give ourselves a few hours’ safety margin,” Watts admits.

The opera was a critical success. The scents told the story of a struggle between nature and industry in four movements, which the programme described as: “Technology joins forces with Nature; Evangelical Green preaches the gospel of modernism, forging a manmade world where scents sound, touch and pour.” Pretentious? Perhaps, or maybe you have to smell it to make sense of it.

Source

Building Sustainable Design

No comments yet