Building on the Thames Gateway’s floodplain involves risk, but with careful planning this can be minimised

With much of central England still reeling from the aftermath of July’s dreadful floods, the widely-perceived vulnerability of Londoners to similar if not worse levels of inundation receives a regular refueling via the national press. So too does our propensity for continuing to build – and indeed to buy – residential property located on floodplains.

The pressure for new homes in the southeast of England is unlikely to abate, and it’s highly likely that a significant proportion of these will be located on the flood plain of the River Thames. (Indeed many of the brownfield sites the government is so keen to see developers build on are themselves located on floodplains.)

Despite public indignation, previous planning policy guidance on flooding has failed to prevent inappropriate development on floodplains, even in the many areas where ageing sewers and drains already struggle to cope, and where further development threatens to reduce the areas of open land available to soak up excess rainfall and floodwater.

“Building on any floodplain involves risk, and the easiest way to avoid that risk would be to build out of floodplains altogether,” admits Chris Burnham, policy and external relations manager for the Environment Agency’s Thames Estuary Programme Team.

Burnham adds, however, that the Agency recognises the many factors involved when identifying land for development, such as the need for local housing or jobs: “If there is little alternative to building in the flood plain to deliver these other sustainable development objectives, it then comes down to understanding the risks, and developing in such a way that, in the unlikely event of a flood, people are safe and damage to property is reduced.”

In London and the Thames Gateway, Burnham explains, there are already over 1.25 million people living and working in the tidal floodplain. Yet most of this is defended to a standard much higher than that elsewhere in the country.

While the Thames Barrier and associated defences provide what the Environment Agency insists is an “excellent” level of protection against flooding in the estuary, sea levels are continuing to rise, and the scientific consensus is that changing climate will make heavy rainfall and stormy conditions more likely in the future.

“Storm surges can raise water levels in the estuary by as much as a metre,” Burnham explains. And while the probability of surface water or fluvial flooding (it was this type which caused so much devastation in Yorkshire and Gloucestershire earlier in the year) is greater in the Thames estuary than that of tidal storm surges, the consequences of the latter would be far worse – “Huge, in fact,” says Burnham, “thanks to the volume and speed of water involved”.

Existing development in the Gateway was built without regard to the possibility of a flood, regeneration gives the opportunity to address that

Not surprisingly then, the main purpose of existing protection in the Thames estuary – which include raised embankments, flood gates and eight barriers, in addition to the Thames Barrier – is to protect people and property from these storm surges

As so much of the existing development in the Thames Gateway was built without regard to the possibility of a flood, regeneration in the region, says Burnham “gives us the opportunity for that to be addressed and factored-in from the start – and it’s an opportunity we must not miss”.

He goes on to explain how planning and design can help mitigate and manage flood risk, ensuring a development does not face flooding problems, irrespective of climate change: “First of all know the risks; by carrying out a flood risk assessment in a flood risk area you can understand the risk of flooding from all sources – tidal, freshwater, surface water and sewers.”

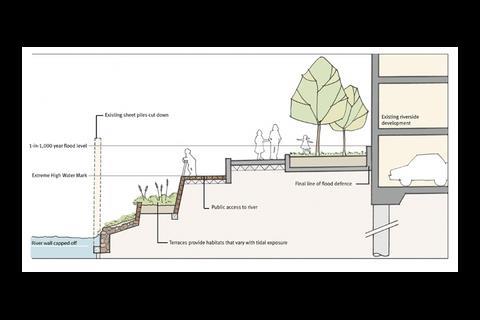

By asking questions such as “where would the water go if there was a flood?” and “how deep would that be and what would be the impact?”, says Burnham, it is possible to identify whether a site is suitable for a particular use and whether it can be developed in a sustainable way. “The most vulnerable areas may be better suited to more flood-compatible use such as landscaped open space, sustainable drainage or car parking,” he adds.

With climate change, Burnham adds, we can expect wetter winters and occasional intense summer rainfall, and this needs to be planned for in the design of both site drainage and layout. “Incorporating sustainable drainage systems into site green space, to deal with rainfall run-off can reduce the risk of the existing drainage systems being overloaded and also provide a great feature and habitat for wildlife.”

If a site is adjacent to flood defences, Burnham warns, it is important to understand that some space should be kept clear for maintenance and improvements to these defences. Such open space not only provides improved public access to the river and better views, he says, citing the attractively landscaped area around the dome in Greenwich, but also allows for the modification or replacement of defences “to deal with increased risks of flooding due to climate change”.

Burnham urges developers and would-be developers to come and talk to the Environment Agency, before they even start masterplanning: “Far too often we receive planning applications which have not considered flood risk, which only causes delays as plans may need to be re-submitted.”

The Agency can help, he adds, “both in advising on the need and scope of flood risk assessments, as well as what you can do to reduce the risks and create a better and safer development”.

Postscript

The Environment Agency will be presenting its latest thinking in the session How safe is it to build on floodplains in the Thames Gateway? at the Thames Gateway Forum on 29 November

Gateway - Autumn 2007

- 1

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

After the flood

- 3

- 4

No comments yet