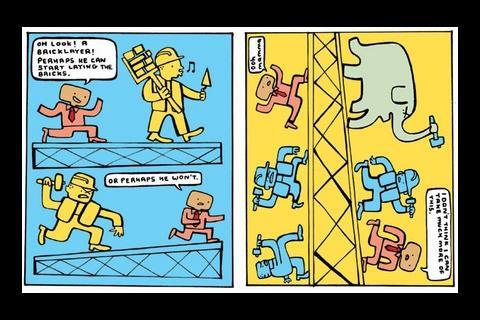

Can a combination of virtual reality sites and actors playing stroppy carpenters prepare workers for a career in construction? Dan Stewart gives it a try

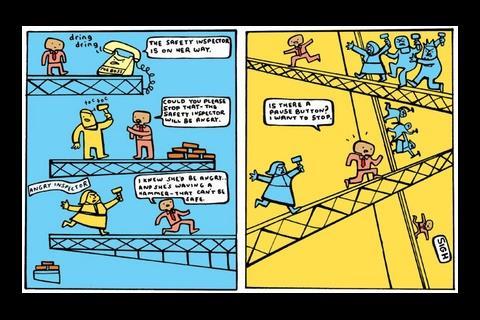

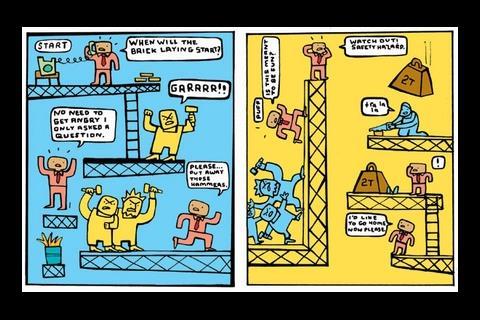

I had only been a site manager for 10 minutes and I was panicking. First, I had to phone a subcontractor to ask when bricklaying would start. They didn’t know. Then my carpenter came into the office to say he wouldn’t work with the foreman any more. Then my boss was on the phone to say the health inspectors were on their way, the site was in a mess and if I didn’t sort it out, my job would be on the line.

Fortunately, this scenario was not being played out on a real site, but on the world’s first virtual reality building site, based in the Netherlands. The “building management simulation centre” (BMSC) employs actors, sound effects and virtual reality technology to help trainee managers learn their trade. Next year, the first British BMSC is due to open at Coventry University.

The benefits of putting employees through their paces in a safe, low-cost environment are obvious, but how do you carry out real-life training in a virtual world?

The BMSC has been designed to mimic the real thing down to the sponsored signs on the walls. Trainees sit at a desk in an actual site hut, surrounded by plans, working telephones and a computer. When the time comes to inspect the site, they don hard hats and head to a gigantic parabolic cinema screen. With the aid of a joystick, they can wander around a computer simulation of the building project. This might sound more like a PlayStation than a training aid, but the high-quality graphics and your position in front of the screen make it dizzyingly realistic.

It’s what goes on in the site huts that constitutes the real training, though. Acting as site managers, trainees are given tasks to perform while actors playing site workers interact with them. Surreptitious cameras relay the results to teachers in a nearby control room, so they can discuss the issues raised in the following class.

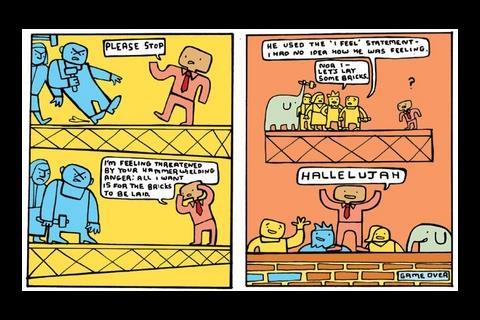

The exercises are not for the faint-hearted. One saw a “site manager” call a “carpenter” in to tell him he was on his first warning. “That’s bullshit!” spat the carpenter, menacingly wielding his hammer. “I’m going to the union!” The hapless trainee watched in silence as the carpenter angrily marched out, slamming the door as he went.

Exchanges like this go beyond role-playing. “It’s a total experience,” says BMSC creator Michiel Schriver. “You become the site manager.” A former engineer, Schriver acts as teacher and director of the simulation centre.

One exercise saw a ‘site manager’ tell a ‘carpenter’ he was on his first warning. ‘That’s bullshit!’ spat the carpenter. ‘I’m going to the union!’

The idea came from a naval simulation centre based near Leeuwarden, the home of the Dutch simulation centre. The BMSC is often compared to a flight simulator, says Schriver, but it is based on human processes in management rather than the interaction between human and machine. The simulation explores the consequences of management decisions, allowing trainees to see what happens when they make mistakes.

Schriver says students get immersed in the simulator quickly. Only two have left it early in the seven-year history, and they did so because they were self-conscious rather than because they were underwhelmed by the experience.

“With the simulator you have to look in the mirror. If you can’t stand your reflection, maybe you’re in the wrong job,” he says. In neither case was the authenticity of the simulator an issue: “Nobody has complained it’s not real enough yet,” he says.

It was this dedication to realism that caught the eye of Lance Saunders, training manager at the Chartered Institute of Building, at a BMSC demonstration in 2001: “I saw the value straight away,” he says. “In the UK we are not good role-players, but the minute you get in this simulator, you’re immersed.”

Saunders took the idea back to the UK where several interested parties came together to form Advanced Construction Technologies (ACT-UK). The group, made up of education and industry leaders, is behind the £8m ACT-UK National Centre, where the BMSC will be housed. Construction is due to start later this year with a scheduled opening date of autumn 2008. As well as the BMSC, the centre will house research labs, meeting rooms and office facilities.

Companies that train employees in the UK will know that a comparable training resource exists in the form of the National Construction College’s Constructionarium.

On this, students learn via the more tangible route of building scaled-down versions of real projects over the course of a week.

A big performance is not what I need. Construction workers don’t talk too much, and they don’t use difficult words. My actors need to become their roles

Leon van Duyvendijk, BMSC actor

Constructionarium co-founder Chris Wise says any course that ignores the physical side of construction can only be partially effective: “[The BMSC] sounds like a good substitute to training on the job, but I do think there’s a difference between the virtual world and the physical world in the construction industry.”

Schriver acknowledges that the BMSC does not simulate technical problems, but says that for any business, management training should come first: “Learning about communication translates to any number of different areas. On a higher level it’s about human capabilities,” he says.

Although the national centre will be based at Coventry University, ACT-UK managing director Harry Hammersley says it is not just for students. “It’s whole-life training. People will use this throughout their career,” he says. The Dutch centre offers 24 courses in different areas of management, and Hammersley hopes to offer a similar range in Coventry. A typical two-and-a-half day course will cost about £1,000 with discounts available for investors and students.

As well as designing a mix of courses for the UK market, ACT-UK will have to find a troupe of actors to play disgruntled carpenters and lazy foremen. Hammersley hopes to find construction workers in the Midlands with a theatrical streak. “It will be quite a challenge, but amateur dramatics are very popular in the UK,” he says.

But the actors will have to do more than learn lines – in the Netherlands, they go through the exercises with trainees and show them where they went wrong. Most are either part-time construction workers, teachers or psychologists.

Leon van Duyvendijk, the artistic leader of the actors, says professional thespians are often not right: “A big performance is not what I need. Construction workers don’t talk too much, and they don’t use difficult words. My actors need to become their roles.”

The strange thing is, the same applies to trainees in the simulator. I entered my site hut prepared to feel professionally cynical, but as soon as the phone started ringing I sank into my role – I had to. I may have panicked after 10 minutes, but by the end of my session I was directing my foreman around the “site”, pointing out safety hazards and telling him if he didn’t clear up his act we’d have to “sit down and have a serious chat”. The teachers were pleased. I’ll make a virtual site manager yet.

Postscript

For more on the Coventry centre, go to www.act-uk.co.uk

No comments yet