As the chancellor gears up for the Autumn Budget, he is under pressure to ease austerity, potentially taking the focus away from big-ticket construction projects. David Blackman reports on what the industry wants from the Budget versus what it is likely to see

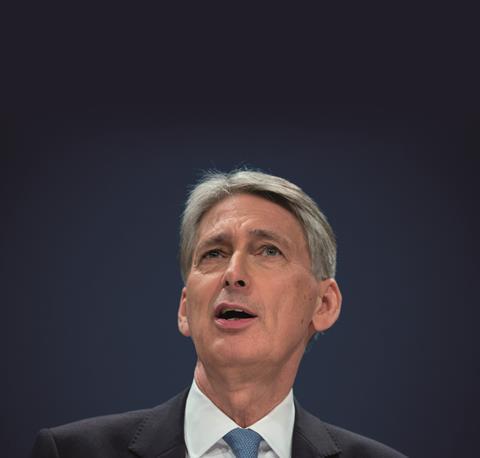

He is unlikely to admit it, but Philip Hammond would be entitled to feel relieved that he only has to deliver one showpiece tax and spending announcement this year. For the first time in 20 years the Budget will take place in November, replacing the Autumn Statement. It means the chancellor of the exchequer will only have one chance to fluff his lines, which Hammond may welcome after having to withdraw a planned extension of self-employed national insurance contributions within days of March’s botched Budget.

If anything, the political backdrop to this announcement is even more charged than earlier this year. During the intervening months, Hammond has become a hate figure for many on the hard Brexit wing of the Conservative Party, who see their own chancellor as the main impediment to their dream of a clean break with the EU.

As a result, it will not just be the Opposition that is set to be looking for opportunities to trip up Hammond on Budget day. On top of that, the state of the UK economy means he is under pressure on all sides. The government’s fiscal situation remains tight, with poor productivity forecasts dampening expectations of future tax growth.

And after the backlash against austerity at June’s general election, demand is loud for the chancellor to increase spending in areas such as public-sector pay and the NHS. It looks like Hammond has an impossible circle to square later this month.

So what does construction want to see in the Budget? And how are its pet projects are likely to fare in the competition for scarce resources?

Housing

Of all the areas that matter to the construction industry, housing should be the big winner on Wednesday 22 November. Prime minister Theresa May identified improved housing supply as her top priority in her key speech at the Conservative Party conference.

“With her commitment to increased housing supply as the prime objective of her premiership, you would expect big-picture announcements,” says Steve Turner, spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation (HBF).

The October summit at 10 Downing Street, when the prime minister invited leading housebuilders to discuss ideas about how to promote housing delivery, shed little light on the government’s intentions, with ministers reportedly in listening rather than speaking mode.

“The meeting itself didn’t move things forward. The fact the prime minister is sitting down with housebuilders and other housing providers is clearly very positive, but it needs to be more than that if it’s going to deliver more numbers,” says Turner.

The housebuilders would have gone into the meeting in a buoyant mood, having already secured their big Budget ask. At the Conservative Party conference, Hammond had announced the £10bn extension of Help to Buy, which should ensure the mortgage underwriting scheme does not run out of funds before 2021.

The next step for the HBF, says a spokesperson, is to secure a decision on whether the scheme itself should be extended beyond its current cut-off point.

However, the government cannot rely on the speculative volume housebuilders to deliver the scale of increased output that it wants to achieve.

Build to rent, which uses institutional investment capital to finance the construction of private rented housing, is one avenue for widening the diversity of provision.

Rachel Kelly, senior policy officer for finance at the British Property Federation, urges the Treasury to give the sector a fillip by easing stamp duty on such developments – which are liable to the same level of duty as other private landlords, undermining the liquidity of the fledgling asset class.

“It’s a huge barrier to a sector that has billions of pounds to put towards housing,” says Kelly, who also urges progress on the Naylor review of NHS estates, which could help release more land for housing while plugging health trusts’ deficits.

Another mechanism is to better mobilise small builders, whose contribution to housing output has dwindled since the recession. The Federation of Master Builders is pushing for the government to adopt a version of plans, touted by Labour in the last parliament, for a scheme to underwrite loans to small developers. Meanwhile, a group of top housing associations have come up with their own plans for a government-underwritten £50bn National Housing Fund.

According to media reports, the prime minister met last week with Hammond and communities secretary Sajid Javid to settle differences in their approach to the housing crisis. Javid had previously pressed for the Treasury to borrow more money to build of hundreds of thousands of homes but been rebuffed by the chancellor. A compromise is now understood to have been reached involving some new money, reforms to planning rules and measures to increase capacity in the construction industry. It is thought the prime minister is still resisting calls to build on green belt. “You would hope there will be more for housing, but whether it would be on the scale of £50bn is doubtful,” says the HBF’s Turner.

And there are concerns that the Budget could set back attempts to widen the gene pool of housing providers. According to reports, the government is preparing to restrict councils’ ability to borrow from the public work loans board to fund property investment deals.

While this move is designed to prevent councils from becoming over-exposed to rash commercial property deals, it could affect their ability to set up local housing companies, which often tap the cut-rate loans available from the public work loans board.

“People are looking for [Hammond] to do things to increase housing supply, whereas there is quite a lot of worry that he will do stuff that has the opposite effect,” says Chris Brown, chief executive of the Aviva-backed Igloo Regeneration Fund.

However, Turner believes the government remains committed to tackling housing, despite wider uncertainty generated by Brexit.

A combination of the election campaign, the formation of a new government and June’s Grenfell Tower disaster have all delayed following up on the housing white paper published back in February. Few elements in the policy package have been implemented. But with the white paper’s chief architect, former housing minister Gavin Barwell, installed as chief of staff at 10 Downing Street, the white paper has a champion at the heart of government.

Infrastructure

A year ago, Hammond identified infrastructure as a priority in his first and last Autumn Statement. However, one year and a general election later, the political environment for big ticket infrastructure projects looks a lot less hospitable.

Admittedly, work on Hinkley Point and HS2 is ramping up, while the government gave the green light to progress on London’s Crossrail 2 project during the summer.

David Leam, director of infrastructure at London First, says of Crossrail 2: “The summer statement by the mayor and the secretary of state was very positive and constructive in terms of setting out a way forward. We have moved on from whether the project makes sense – now it’s more about how to pay for it.”

However, on other major projects, progress has stalled. The Department for Transport has just embarked on yet another round of consultation on plans for Heathrow airport’s third runway.

A parliamentary vote on the relevant national planning statement – which is required before the project can go ahead – is not expected until mid 2018.

“It’s all a bit later than we hoped a year ago. It’s frustrating how long and slow this process is,” says Leam. “The worry is that there always seems to be a bit of slippage – the risk is that down the line it opens years later than it should.”

There was also bad news during the summer for the so-called northern powerhouse rail project, designed to provide faster train connections between the region’s major cities.

Leam, keen to avoid the battle for transport funding becoming an inter-regional competition, wants to see progress on these plans. He says: “The key thing in the Budget will be to spell out a more comprehensive plan for transport investment in the north.”

Alexander Jan, director of city economics at Arup, says it is also important for the government to commit some funds for Network Rail’s forward (as opposed to current) capital programme, which had to go back to the drawing board following the overspend fiascos on the Midland Main Line and Great Western electrification projects.

“The government should signal how that process is being supported in order to allow Network Rail to maximise development opportunities at stations such as Bristol and Cardiff,” says Jan, who is working on plans to help regenerate the area around Bristol Temple Meads station.

Even more important is giving councils more powers to raise and retain business rates so that local leaders can push infrastructure projects forward themselves.

Pressure on Hammond has grown over the past year to divert money into current spending such as public-sector pay from longer-term capital projects. However, Leam argues that it is important the government should not lose its focus on infrastructure amid more immediate pressures.

He says: “We would absolutely emphasise that while the government is grappling with Brexit, it’s critical that we address long-standing challenges we face as a country. We recognise that the chancellor is between a rock and a hard place, but in terms of capital spending and long-term commitment to infrastructure we would like to see him recommit to that.”

And Leam believes investment in housing and infrastructure could help the Treasury tackle one of its biggest challenges – the UK’s lagging productivity – but only if that investment is made in the right locations. The government needs to take into account not only the cost-benefit analysis of individual projects but also the wider benefits for productivity.

“If you build a house in the South-east and London, it helps with the productivity challenge because London and the South-east is the most productive part of the economy. A signal from Treasury that they understand this is about housing growth and therefore they need to treat it differently from the conventional ways of doing things would be welcome.”

Follow our expert live Budget coverage and analysis online on Wednesday 22 November

No comments yet