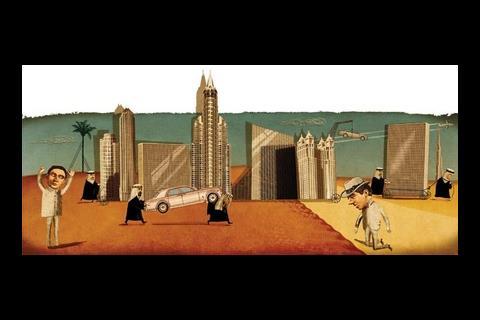

Dubai’s boom fed a lifestyle of fast cars and luxury flats that construction professionals could never have dreamed of back home. But now, as grim reality sets in, many expats are finding that redundancy is also done very differently in the Gulf

At Dubai’s gleaming airport, brand new cars are being dumped in the car park by unemployed expats unable to pay back the loans they took out to buy them. There is surely no clearer sign that Dubai’s once seemingly endless growth is coming to a screeching halt. The expats are heading home or on to try their luck in some other part of the Middle East.

In Dubai, if you have a job, you can get a working visa. But as soon as you lose your job, life can very quickly get sticky. On the last day of your employment, your employer will ring your bank and tell them you have been made redundant. The bank will then freeze your account.

From there, the problems gather speed. Anyone without a job loses their visa, and without one, you can’t stay in Dubai. In fact, people have a grace period of 30 days before they have to leave. People in this position have three options. The first is to stay and find the first job available, assuming there is such a thing. The second is to drive to Oman, an hour and a half away, then turn around and come back to Dubai on a four-week tourist visa. This route, however, is being clamped down on and now people face the longer and considerably more expensive trip to Qatar – a $600 flight away. The third option is to cut and run – dumping your car if need be.

Paul, and his friend Simon (not their real names), both in their early thirties, have just lost their jobs in Dubai’s construction industry. Simon says that cars are being abandoned at the rate of 30 a week and have been since the start of the year. Paul owns one – a 4x4 – and Simon owns two – a 4x4 and a sports car. Simon took out a £30,000 loan to buy his.

Both Simon and Paul have until mid-May to come up with the money. Simon says he’s worried about the cars more than anything else. He has already tried to offload the sports car – he had a buyer lined up but, maddeningly, was told by his bank that he first had to pay the loan off before they would let him sell it. The dealers won’t take the cars back, either. “If I don’t find a job,” he admits, “I’m screwed.”

The pair came out to Dubai nearly two years ago and met on the flight out. Paul was working for Mouchel; Simon prefers not to say. “I don’t want to burn any bridges,” he explains.

They both worked on schemes for Nakheel, the state-owned developer behind some of Dubai’s biggest jobs, including the 1km-high tower that has suddenly been shelved after being announced in November with massive fanfare. For Paul the chance to earn money tax free was a big draw. “Also my wife adores sunshine and I thought working out here would look good on the CV,” he says.

Simon, on the other hand, was single and fancied a change. “I was doing a four-hour commute in England and I was given an opportunity to lift my salary by 12%, plus I wasn’t taxed.”

Initially things were great and both lived by the sea, marvelling at the azure skies and golden sands. It was a bit like being on holiday. “My salary increased and everything I earned went into my pocket,” says Paul.

The pair did the sort of things they would never have done back home. Simon remembers learning to scuba dive and going skiing at the giant indoor ski centre virtually every week.

Sometimes I think it is a hellish place to live. It’s the small things like being paid in Kit Kats in the supermarket because the check-outs don’t have the right change

'Simon'

It was a good life. So good, in fact, that landlords spied an opportunity and changed rental terms almost overnight. Previously, tenants would give them three post-dated cheques to be cashed every four months, but a year ago landlords started demanding 12 months’ rent upfront – a major shift when villas cost anywhere between £20,000 and £40,000 a year to rent. Many ex-pats have had to take out personal loans to raise the money.

Simon’s villa is costing close to £40,000, and Paul’s is not too far behind. So, what do they do when the time to renew the contract comes around? Simon has had enough and is wants to leave, but Paul is keeping a more open mind. “I won’t be doing a runner, but I’m fed up with Dubai and the nonsense you have to put up with on a daily basis,” says Simon. “Sometimes I think it is a hellish place to live. It’s the small things like going to the supermarket, and being paid in Kit Kats because the check-outs don’t have the right change.”

In November last year it became obvious that Dubai was heading towards disaster. “It’s a peculiar place,” Paul says, “because you find a lot out by rumour. For a long time if you mentioned the credit crunch, people would go bananas. But I remember in November Nakheel opening the Atlantis hotel and spending $20m on fireworks and then virtually the next day laying 500 people off. After that, things changed very, very quickly.”

Simon and Paul should know because around a month after Nakheel dropped its bombshell, they too were given their notices. Other UK firms are cutting and re-jigging staff in Dubai. Atkins, Carillion, EC Harris, Halcrow, Laing O’Rourke, Davis Langdon and Mace have all done it. Swiss bank UBS recently put out a report which predicted that 30% of all construction jobs in Dubai could be lost this year and next. In turn, it said this would lead to 10% of foreigners leaving.

Simon expects to be one of them. “I’m looking at other parts of the Middle East where it’s tax free whether it’s Saudi Arabia, Oman or Bahrain.” He doesn’t want to go back to England and neither does Paul, who says: “If I went home now, it wouldn’t be on my terms. I’m looking at jobs in the whole of the Middle East.”

Wherever Simon and Paul and hundreds more like them end up, it will be difficult to replicate their experiences in Dubai. Take Saudi Arabia, for instance – the managing director of specialist recruiter Digby Morris calls it “hardship posting” – you live in a compound, can’t drink alcohol, and women have to cover up and aren’t allowed to drive. “You have to think about the implications of living and working there,” Neil Morris says. Paul already has. “My wife wouldn’t tolerate some of it. I may have to work in Saudi but live somewhere else.”

Neither Paul nor Simon regrets going to Dubai. “Most people have lived like kings, drive flash cars and live in villas with three toilets.” But the glitz has worn off, and in short, people have run out of money. “We’re all guilty of it,” says Paul. “I came out here and set up another home. I needn’t have bothered.”

David Yaw, the regional managing director of Halcrow, first went out to the Gulf in the seventies. He says Dubai is coming to terms with its new role in the global economy. “The economies of Dubai and the Middle East are integral to the world economy now. Globalisation is here. A lot of people have lived on borrowed money and that causes problems when the rest of the world crashes.”

Had he known what was coming down the track, Simon thinks he might have done things a bit differently, spent less and lived more frugally. He pauses for a moment and then adds: “But that’s not Dubai’s fault.”

Where Dubai went wrong

More than any other state in the UAE, Dubai, with no oil or gas reserves to bankroll its building boom, relied on international credit. Last summer, that pipeline was squeezed, causing havoc in Dubai’s property market.

Much stricter lending criteria meant that speculative developments were harder to get off the ground. Before, investors could put a small deposit on an apartment and sell on – or “flip” – the contract for profit long before the building was completed. But flippers got caught out when lenders stopped underwriting their activities. What had been a get-rich scheme quickly turned into a quagmire of desperate flippers trying to get rid of units they had no chance of meeting payments on.

And because no one was buying, development stopped. Hundreds of people hired in the construction industry on the assumption that the building boom would continue are now losing their jobs.

Redundancy, Dubai-style

Nearly everyone is hired on a local contract and people laid off get redundancy money out of a “gratuity” fund they have paid into. The amount people end up with is a grey area, but it tends to be one week’s pay for every year worked. This compares with one month for every year in the UK. In other words, if you worked for a company for 10 years and got laid off in the UK, you would get 10 months’ pay, but if you happened to have transferred to Dubai, you may only get 10 weeks. Those with the foresight to have renegotiated better contracts will fare better, but many are thought not to have looked closely at their contracts or really considered the possibility of losing their job. Halcrow’s David Yaw says many western companies do try to lessen the impact of redundancy as best they can.

Despite the crash, the appetite for candidates to work out there is still strong. Neil Morris, manager of construction at recruitment firm Hay’s UAE division, says the CVs are still coming in. Competition is fierce, he says, because of the attractions. Previous Middle East experience is almost a pre-requisite.

More on the UAE’s labour laws can be found at www.zu.ac.ae/library/html/UAEInfo/documents/UAELabourLaw.pdf or www.fco.gov.uk/en

5 Readers' comments